When refugees camps last three generations, we must accept they’re not going anywhere

Kilian Kleinschmidt worked with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) for 25 years and then quit in frustration while trying to build the Za’atari refugee camp (paywall) for displaced Syrians in Jordan.

Kilian Kleinschmidt worked with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) for 25 years and then quit in frustration while trying to build the Za’atari refugee camp (paywall) for displaced Syrians in Jordan.

“We’re doing humanitarian aid as we did 70 years ago after the second world war,” he told Dezeen. Nothing has changed. In the Middle East, we were building camps: storage facilities for people. But the refugees were building a city.”

Kleinschmidt describes refugee camps as the “cities of tomorrow” and he’s not wrong. Refugees are expected to wait in these camps until they can either return home, be integrated into the host country, or be resettled. With no foreseeable end to the wars ravaging a number of countries and many rich nations turning their backs to refugees, an increasing number of the world’s refugee population find themselves waiting for decades.

Refugee camps were initially designed to be a short-term solution to an emergency situation, but the average stay is now 17 years.When refugee camps were set up for the Palestinians after the establishment of Israel, the UN looked after 750,000 Palestine refugees. Today, there are five million Palestine refugees.

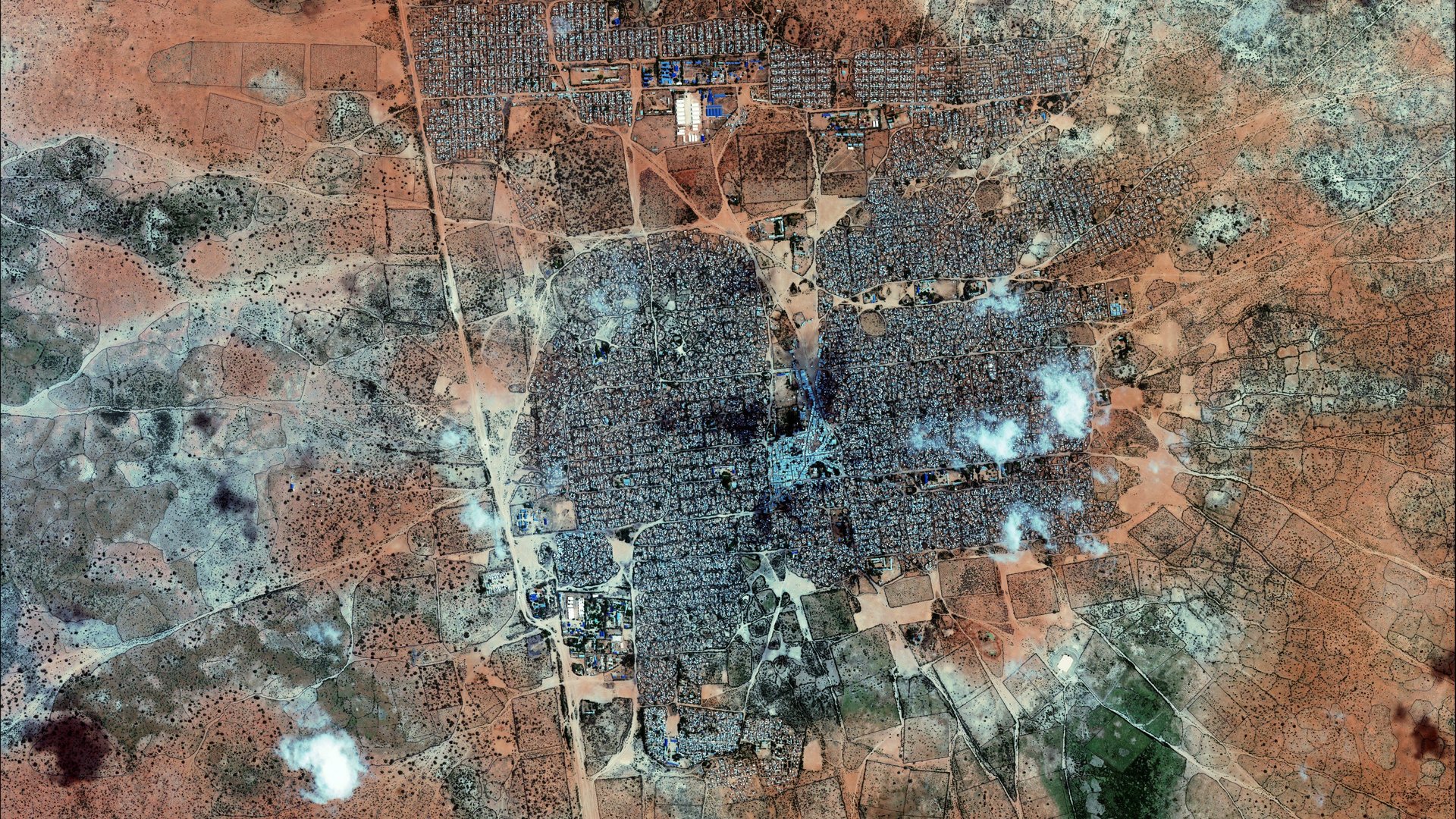

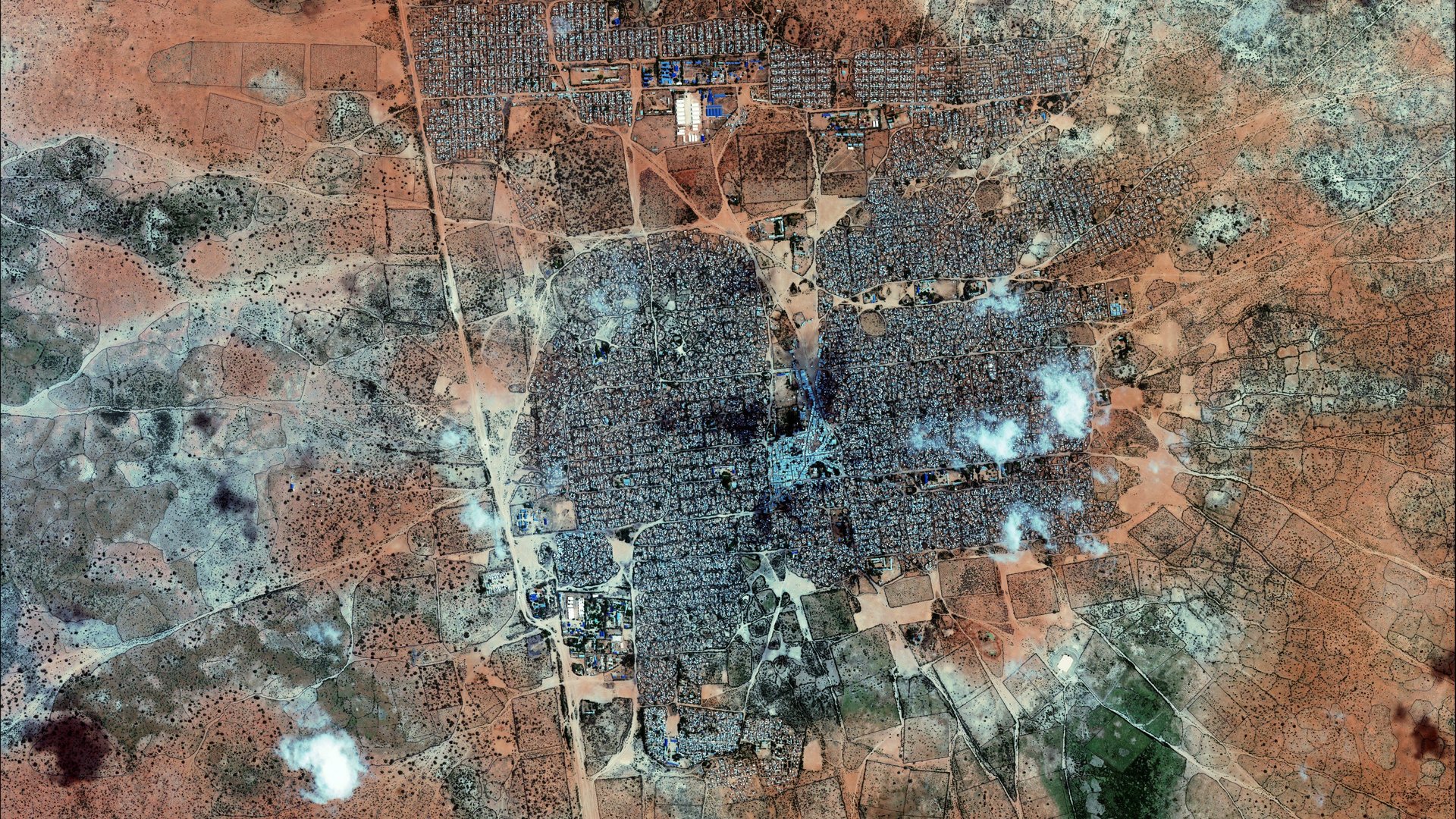

Thousands of Somali refugees arrived at the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya in 1991 and the camp still continues to grow. If it was a city, it would be the fourth-largest in Kenya.

Dadaab, now home to 463,000 refugees—10,000 of whom are third-generation refugees born in the camp—is somewhat frozen in time. Refugees are not allowed to leave the camp unless they receive a special pass, there are no jobs—only volunteer positions—and spots in higher educations in the camp are fiercely contested. The UN isn’t able to build permanent structures because the Kenyan government forbids it, water still comes from temporary taps and food is still bussed in.

Kleinschmidt blames “the stupidity of the aid organizations, who prefer to waste money and work in a non-sustainable way.”

Refugee camps can be expensive to run as they have to meet international standards. The UNHCR recommends that each refugee receive more than 2,100 calories and 20 liters of water per person per day; a minimum of one toilet per 20 people; decent accommodation, schools, and health centers.

“Refugee camps are the last resort, it’s not the preferred solution,” Céline Schmitt, a UNHCR spokeswoman, told Quartz. The UN has on numerous occasions called for “durable solutions” to the world’s refugee crisis, but world leaders have failed to respond.

A poorly planned refugee camp is a recipe for disaster; nothing represents this so spectacularly as the sprawling refugee makeshift camp at the heart of Europe—the Jungle. Overcrowding, the lack of adequate shelter, and unhygienic conditions can quickly result in outbreaks of debilitating diseases.

To help them best coordinate space, shelters and facilities, many aid agencies use satellite imagery. ”Our imagery shows the human impact of the crisis,” Taner Kodanaz, director of DigitalGlobe, tells Quartz. “It become a very powerful storytelling mechanism.”

Satellite imagery of Dadaab, for example, shows the devastating environmental impact; a lot of the trees in the area has been decimated because of the refugees in this region, and how larger buildings and structures have been gridded to resemble mini towns. Kodanaz points out that “no-one intends these to be long-term institutions,” but Dadaab represent a truth the international development are unwilling to swallow; refugee camps are increasingly becoming permanent fixtures.

Kleinschmidt suggests countries like Jordan and Pakistan, which hosts a large number of the world’s refugees, are losing an opportunity by continuing to treat refugees and the camps they live in as a temporary problem. The refugees in Dadaab, to take an example, have the potential to be a huge asset to the Kenyan economy, if the government would integrate them.

A 2010 study commissioned by the Kenyan, Danish, and Norwegian governments found that Dadaab brings around $14 million into the surrounding community each year. Germany, which could see up to a million refugees arrive this year, may soon begin to reap the benefits of letting in so many people.

But to get those benefits, governments will have to no longer pretend these camps are temporary problems. Take Tanzania as a rare positive example. After denying them citizenship for several decades, the Tanzanian government finally decided to naturalize hundreds of thousands of Burundian refugees, who first fled their country in 1972, in 2010.

A previous version of this post stated the Za’atari refugee camp is in Lebanon, when it’s in northern Jordan.