Ok, so there are some very obvious differences between the two photos below.

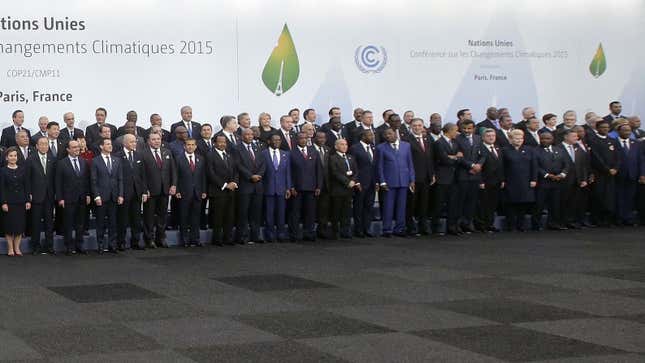

The first was taken today (Nov. 30) at the COP21 climate conference taking place near Paris. It’s a formal group shot featuring, among others, David Cameron and prince Charles of the UK, Xi Jinping of China, François Hollande of France, Barack Obama of the US, and, hidden to the extreme right, Angela Merkel of Germany:

The other was taken six years ago, at the COP15 conference in Copenhagen:

In the 2009 picture, the leaders appear to be getting down to business. Merkel is speaking to a group that includes José Manuel Barroso, then with the European Commission, France’s then-president Nicholas Sarkozy, Obama again, and the UK’s then-prime minister, Gordon Brown.

So what’s the crucial difference in the role that world leaders at the COP had then and now?

As with comedy, it’s all in the timing.

In 2009, the heads of state were invited at the end of the conference, notes Tim Baines, a climate change and clean energy lawyer with Norton Rose Fulbright in London. (The day the 2009 photo was taken, Dec. 18, was the last day of the summit.) Their last-minute negotiating essentially was for naught—the 2009 meeting ended in a weak agreement that recognized the need to keep global warming below a 2°C threshold but didn’t bind countries to making that happen, and the talks were widely seen as a failure.

This year, the world leaders have all been invited at the beginning of the conference. After making an initial diplomatic show, they’ll then depart, leaving the hashing-out of a climate deal to expert negotiators.

The conference is due to last at least two weeks, and might go on longer. (Though it’s meant to wrap up on Dec. 11, a Saturday, Baines also notes that the French hosts of COP21 have booked the conference venue through midnight the following Monday.)

So while in Copehagen, the entrance of the leaders signaled a last-ditch, desperate attempt to secure consensus—and arguably delayed that possibility until they arrived—this year they’re not planning to step in at the 11th hour.

It remains to be seen if the new tactic will change anything, and how much Merkel or Obama—or, perhaps, more likely, Narendra Modi—will need to wrestle with any deal reached in the next two weeks. But in terms of people management, it might be a stroke of genius.