China plans to pull its enormous shadow banking system into daylight

China’s unofficial, off-balance-sheet lending has for months greatly exceeded formal bank lending. And the massive size of the “shadow banking” sector has raised fears of a credit meltdown. It remains unknown which projects shadow loans are funding and whether they will be able to repay debts.

China’s unofficial, off-balance-sheet lending has for months greatly exceeded formal bank lending. And the massive size of the “shadow banking” sector has raised fears of a credit meltdown. It remains unknown which projects shadow loans are funding and whether they will be able to repay debts.

The FT reports, however, that China’s government will drag shadow banking into daylight by forcing banks to disclose their off balance sheet lending to regulators. This is likely because many such loans are really funded by unsuspecting retail depositors who think they are buying high-yield credit investments. Some of these so-called “wealth management products” (WMPs) have blown up, leaving empty handed savers protesting outside bank branches.

As Reuters outlined here, such products have funded risky schemes including “a near empty housing project…at the end of a dirt path amid rice fields in one of China’s poorest provinces.”

Shadow banking is becoming the main engine of China’s credit driven growth. The nation’s local governments sell land to developers to raise cash. Real estate and infrastructure projects create jobs and help bureaucrats meet GDP growth targets. But China’s growing surfeit of empty malls and ghost towns shows this model is unsustainable. Worried about being overly exposed to unviable schemes, banks have officially cut lending to property and infrastructure projects. So these borrowers turn to shadow bank products – which refers to any source of non traditional credit – instead.

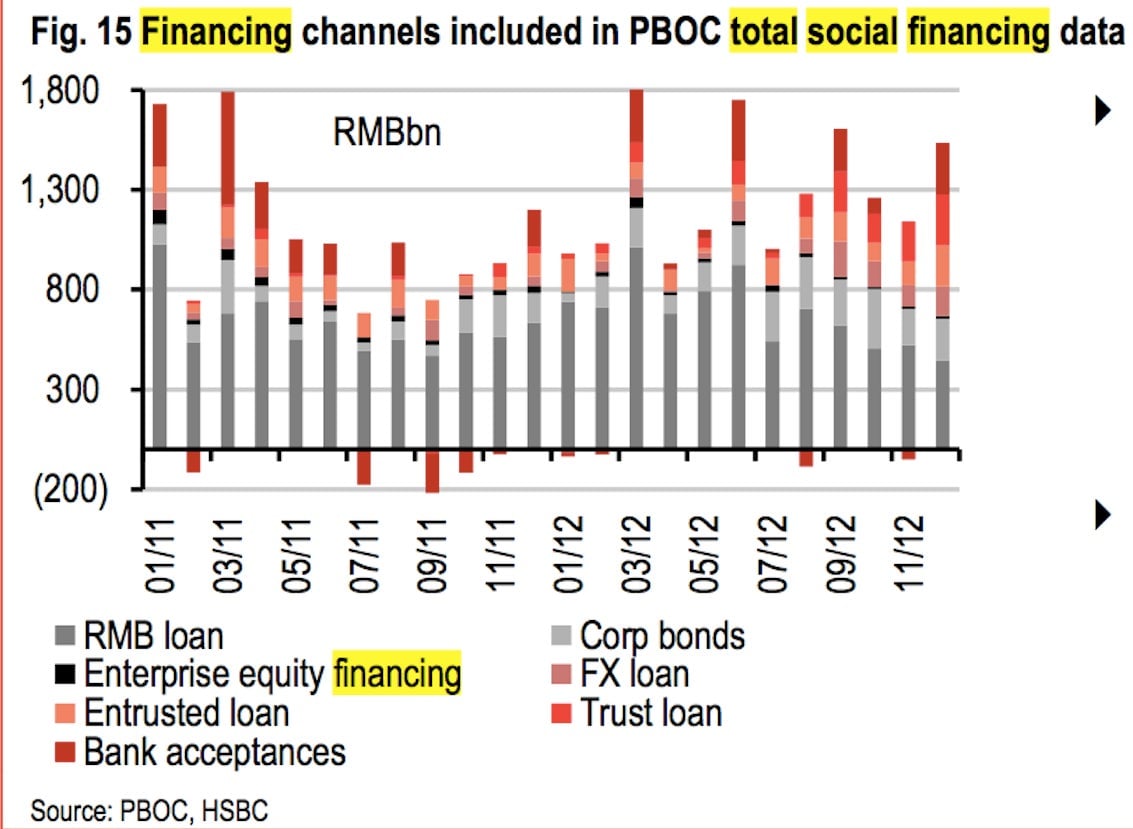

Chinese credit reached a record 177% of GDP last year, according to an HSBC report published last month. Meanwhile, as this chart from HSBC shows, formal bank lending is an ever-decreasing proportion of what Chinese bank analysts call “total social financing”. (This refers to WMPs and other shadow financing instruments the WMPs may invest in, such as real estate trust loans.)

A significant portion of the WMPs seems to resemble Ponzi schemes. Analysts suspect they use money paid in by new investors to hand existing investors returns. That may be because the schemes the WMPs have lent money to are not able to repay debts.

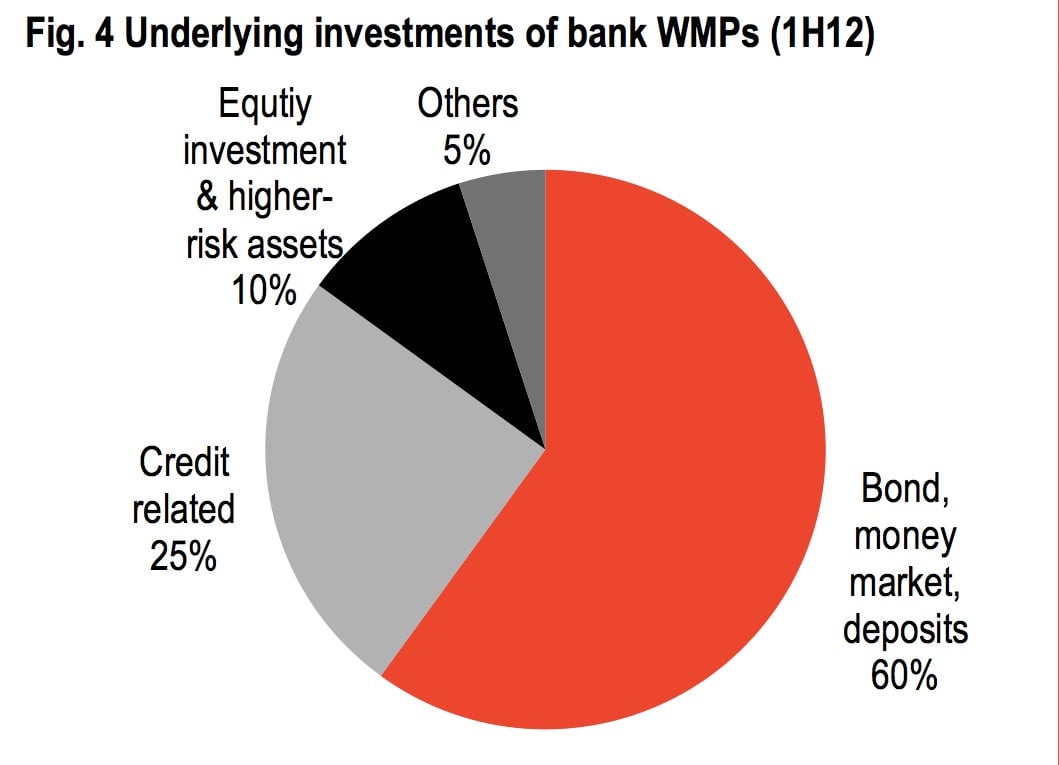

HSBC, which analysed data from nearly 75,000 WMPs, found that while around 60% of wealth management products are invested in lower risk money market funds, a sizeable minority of 25% or more are ploughing funds into credit products, which would include property and infrastructure loans or trusts. The latter category pay high yields of 8-10% and are sold to rich people with at least 500,000 yuan ($79,000) to invest.

The high involvement of ordinary savers and wealthy individuals in China’s shadow banking system may be why the government is clamping down. The Chinese state is the majority shareholder in most of the nation’s large banks. And the banks themselves are the main source of funding for the large, monopolistic government-backed companies called “state-owned enterprises.” So the last thing China needs is a crisis of confidence in its financial system, sparked by a mass meltdown of WMPs and which could cause runs on its banks. Without easy shadow banking cash, however, GDP-boosting real estate and infrastructure projects could stall, curtailing China’s growth. Beijing has tough choices ahead.