So, shockingly, US Federal Reserve chief Ben Bernanke hasn’t made any major alternations to the central bank’s carefully crafted communications on how long interest rates will stay low today.

But Bernanke’s semi-annual, two-day testimony before Congress has trodden on some new ground so far.

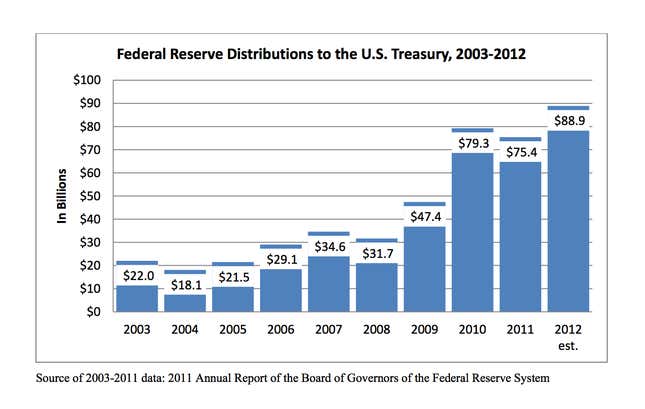

The chairman slipped in a section on the billions of dollars in interest income it cycles back to the coffers of the US government each year. As you can see, those payments have surged in recent years.

Why are they up?

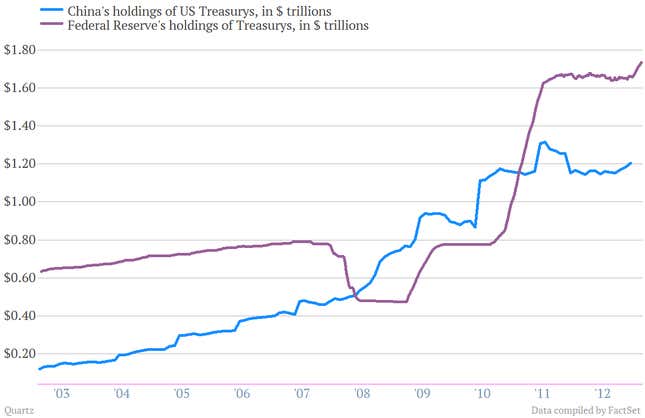

Because the Fed has devoured a huge amount of interest-paying bonds, mostly US Treasury securities. In fact, you can see that the Federal Reserve is now the biggest single holder of Uncle Sam’s publicly held debt, thanks to all of the holdings of US Treasurys in its portfolio. Those holdings are even bigger than China’s.

Here’s what Bernanke has to say about it:

With the expansion of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet, yearly remittances have roughly tripled in recent years, with payments to the Treasury totaling approximately $290 billion between 2009 and 2012. However, if the economy continues to strengthen, as we anticipate, and policy accommodation is accordingly reduced, these remittances would likely decline in coming years. Federal Reserve analysis shows that remittances to the Treasury could be quite low for a time in some scenarios, particularly if interest rates were to rise quickly.

However, even in such scenarios, it is highly likely that average annual remittances over the period affected by the Federal Reserve’s purchases will remain higher than the pre-crisis norm, perhaps substantially so. Moreover, to the extent that monetary policy promotes growth and job creation, the resulting reduction in the federal deficit would dwarf any variation in the Federal Reserve’s remittances to the Treasury.

This seems to be the first time that Bernanke has brought up the fact that Fed payments to the Treasury might decline in his semiannual testimony. And one way you could read this is that the Fed is trying to prepare the political class, in a tip-toeing and roundabout way, for the fact that interest rates might start to rise—not necessarily surge, but rise—after being kept at record lows for several years. Granted, there is absolutely no indication the Fed is going to move toward tightening monetary policy any time soon, despite recent noises about it from members of the Fed’s Open Market Committee. But in his discussion of the Fed’s payments to the Treasury, Bernanke is subtly flicking at it. And that, in itself, is important.