Every year around this time, Americans engage in a cultural battle. Some of us lament that the true meaning of Christmas has been subsumed by consumerism. Others rail that commercial products aren’t Christmas-y enough. That Starbucks’ holiday-themed cups didn’t bother to say “Merry Christmas” was enough to inspire viral internet outrage.

These plaintiffs either fear that religious diversity and political correctness, or that unchecked capitalism, have corrupted the pure, Christian roots of the holiday. But both sides are wrong.

The Christmas holiday has always been less about celebrating the birth of Jesus than about commerce, religious dominance, civic power, and heavy drinking. For centuries, in Europe and stateside, the Christmas spirit was actually about imbibing spirits.

Christmas is really a multicultural mash-up of pre-Christian and Pagan holidays, and what Stephen Nissenbaum, in The Battle for Christmas, calls “an invented tradition”: “customs that are made up with the precise purpose of appearing old fashioned.”

In fact, Christmas as we know it today is only a couple of centuries old, a byproduct of the industrial revolution and shifting social classes. But since, it has been inextricably linked with consumerism.

This year, Americans may spend more on Christmas than they have since 2007, a Gallup poll revealed. The National Retail Federation expects holiday sales to hit $630.5 billion in 2015, accounting for around 20% of annual retail spending, and at least a small chunk of our almost $18 trillion GDP.

Don’t be disgusted by that. That truly is the modern Christmas spirit.

December is a fine time for a party

In theory, we’re all celebrating Jesus’s birthday on Dec. 25, but scholars have long noted that there’s no mention of this date in the bible. What made the date attractive to Christian leaders was that December had for centuries been a prime party month.

In many areas of Europe, December meant feast time. So that they didn’t have to be fed during the winter, cattle were slaughtered and supped upon. Pagan sun worshippers celebrated the winter solstice, the beginning of the end of those dark days. The Norse celebrated Yule from the winter solstice through January, burning big logs and feasting until they’d turned to smoldering ash (hence, the infamous video of the Yule log).

The Romans’ Saturnalia, the week before the solstice, consisted mostly of drinking and eating, and businesses were shuttered so even the lowest echelons of society could join in the fun.

There was another, equally important aspect to these celebrations: many included a kind of social inversion. For the length of the celebration, the lower classes of society assumed the pretense of power. They were given time off or served meals by their owners or employers; this is, some say, from whence the notion of Christmas gift-giving came.

In the 4th century, church leaders, elbowing to get a little more traction in the religious marketplace, agreed to mark Dec. 25, just after the solstice, as the Christmas date. It’s basically like tagging a new show onto a hit lineup. Or, as Nissenbaum writes, Christmas is “nothing but a pagan festival covered with a Christian veneer.”

Christmas: Mardi Gras in December

By the 17th century, Christmas had become such a bacchanalian affair that it seemed downright un-Christian. “When the Puritans came to power in England, the first year they ran things they banned the celebration of Christmas,” Nissenbaum told me. “Ostensibly the reason was biblical, but everybody said this holiday is just too raunchy.”

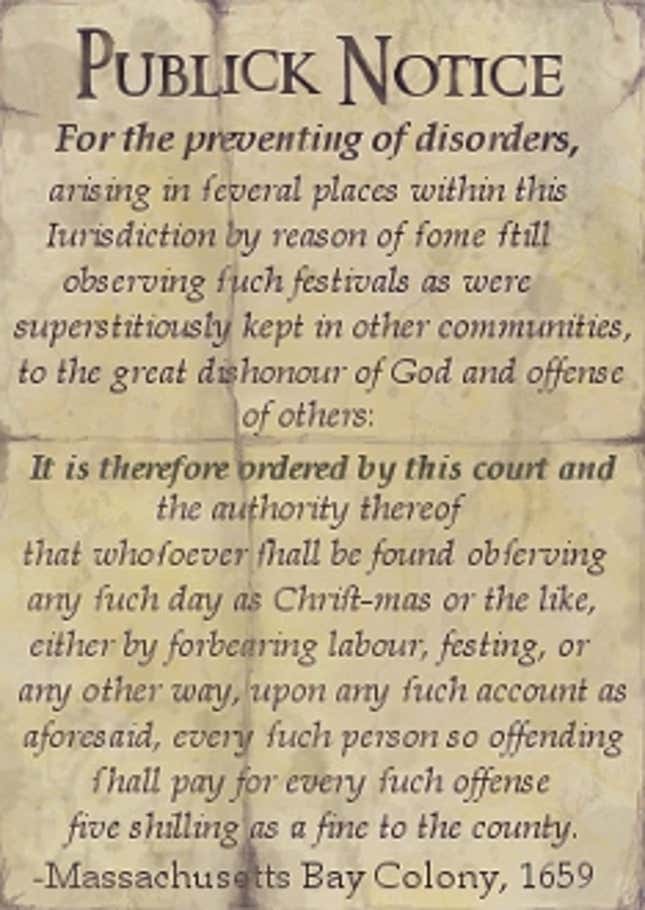

Between 1659 and 1681 it was illegal to celebrate Christmas in Massachusetts; doing so incurred a five-shilling fine.

But even the Puritans couldn’t kill it. In the early 19th century in the US and in many places in Europe, the annual parties raged on, continuing some version of the social inversion theme.

Bands of lower class people would bang on the doors of the upper crust, demanding food and drink. “They’d say, ‘We don’t want you to give us your weak beer; we want you to give us your best, your strongest beer. We don’t want your lousy bread; we want cake. We want you to give us the stuff you would normally give yourself,’” says Nissenbaum.

This was all fine and well, he says, before the 19th century and the industrial revolution, when the people banging on your mansion doors were your own employees, people whom you knew, and who would resume the social order once they slept off that strong beer and cake.

But with the industrial revolution, Nissenbaum argues, came social and economic segregation. The wealthy lived in areas closed off from the poor, and those marauding gangs were no longer comprised of familiar, controllable people, but menacing, dangerous strangers. Christmas, it seemed, had to be controlled.

Bringing Christmas inside

How to take back Christmas? In America, and specifically in New York, an almost conscious rebranding of Christmas got underway. Many scholars believe that Christmas as we know it today was institutionalized between 1800 and 1880.

“The main stakeholders in [the reinvention of Christmas] were prosperous people who were living in nice houses with nice lawns and probably gates surrounding them,” Nissenbaum says. The elite, he says, helped developed new rituals to get Christmas off the street and into the home, away from the nice houses and nice lawns.

According to The Battle for Christmas, newspapers, generally owned by the wealthy elite, began reporting Christmas shenanigans as crime, not as a social norm, and stories of Santa Claus—a figure borrowed and shaped from European versions, including Saint Nicholas of Myra and the Norse god Oden—became enmeshed in the Christmas myth. Writers like Washington Irving, Charles Dickens, and Clement Clarke Moore furthered a simultaneously new and nostalgic depiction of Christmas, though it was nostalgia for a time that never was.

Price Albert, after marrying Queen Victoria in 1840, helped to popularize in England the German tradition of decorating evergreens. Soon after the image of the royal family before their Christmas tree was published in 1848, Americans caught Christmas tree fever (and gave birth to the modern tinsel industry). There are now some 30 million Christmas trees sold annually in the United States.

All of this was great news for the merchant class. Not only were their stores no longer threatened by marauding gangs, but also their wares would now get an extra boost, as people purchased items for their families instead of booze for their workers.

“Gift giving became pervasive, with new categories of givers and recipients participating in exchanges, and with many types of items considered suitable as gifts,” writes William Waits in The Modern Christmas in America: A Cultural History of Gift Giving. After 1880, manufactured goods were more readily given as gifts than handmade ones.

From there other commercial traditions grew, Christmas Creep; Black Friday and its offspring; the Christmas-themed muzak that drives shoppers bananas (good thing we have Cyber Monday so we can avoid actual brick-and-mortar stores!). Christmas has become so synonymous with consumerism that one group started Buy Nothing Christmas as an antidote to it.

The true spirit of Christmas remains

Even after Christmas was tamed and brought indoors—it was declared a federal holiday in 1870—one aspect of it remained true: there was still a kind of social inversion, except it was relegated to the familial sphere. Once upon a time in America, children were meant to be disciplined, seen-but-not-heard, and groomed for labor. They were not there to be catered to except, in Victorian times in the West, on Christmas. Train sets and dolls bestowed by parents replaced the booze and baked goods that the wealthy bestowed upon the poor on Christmas.

Right about now the guy so offended by Starbucks’ red cups is getting ready to throttle me for my blasphemy. Christmas, he might remind me, started because Christians wanted to celebrate the birth of Christ—Easter was the big holiday, but why not mark the day he arrived, not just the day he rose from death? Church leaders may have positioned it for maximum appeal, the wealthy elite may have massaged the way we celebrate it to benefit themselves, but the reason for the holiday’s existence cannot be untethered.

True. It’s just, well, that’s always been a very marginal part of the Christmas experience. “There have always been people who have wanted it to be celebrated in a devotional way to honor the birth of Christ,” says Nissenbaum. And yet: “Those people were never in the majority in any kind of meaningful way.” He adds, “Christmas has proven extremely difficult to Christianize.”