In sports, cross-generational comparison of the historical greats provides endless fodder for family arguments, podcast and radio diatribes, social media trolling, bar fights, and general contentiousness between fans old and young. Why? Because despite our modern obsession with metrics, there is no definitive truth in these comparisons. Brady vs Montana? Serena vs Graf? LeBron vs Magic ? While statistics can be measured across eras, the game changes. Humans evolve. Everything from equipment, to performance enhancing drugs, to non-smoking rules in arenas, to comfort in air travel makes what-that-guy-did-then different from what-this-guy’s-doing-now.

While we know greatness when we see it, we are perpetually contrasting the greatness before us with the greatness that came before, secretly knowing there is rarely an indisputable answer. We use these conversations to connect with each other. There’s space for everyone in the argument, and we learn one another by how we advocate for the unproveable.

But in music, we don’t really have metrics to use to compare stars across generations. Album sales? Nope, thanks to Shawn Fanning and Napster. Grammys? Milli Vanilli once won Best New Artist. Ticket sales? There are country stars you’ve never heard of who played to more people last year than most pop stars. But like in sports, we know an artist at the peak of her greatness when we see it. And anyone who was paying attention in 2015 knows Taylor Swift just submitted one of the four greatest years of any musical artist in history.

Taylor Swift’s 2015

In 2015 Taylor redefined what it means to be a star. She completed her musical transition from country to pop, had the most ubiquitous album of this generation, and toured the world playing stadium shows from Tampa Bay to Shanghai. She became such a force that almost nightly, other artists and personalities used her stage to further their own careers through guest appearances. Her platform became bigger than Oprah’s. Was there anything weirder than Chris Rock parading down a runway to a crowd full of moms and daughters? And yet it made sense — her runway was for everyone.

Indie-rock darling Ryan Adams non-ironically covered the entire 1989 album and released it, rejuvenating his career in the process. She released the Bad Blood video, a five-minute action movie filled with more cameos by beautiful people than any video since George Michael’s Freedom ’90 (Cindy Crawford was in both). The video was watched on YouTube more than 681 million times, and sent a resounding message about the power and strength of Taylor’s inner circle of female friends; multi-talented, diverse, and united. It was a not-so-subtle dig at her pop-rival Katy Perry, revenge for the poaching of a backup dancer, and a clear message: don’t tread on me.

She taught us forgiveness, contrition, and compassion. She reconciled publicly with Kanye West — who had disrespected her on live television years earlier and left her in tears — while apologizing publicly and earnestly to Nicki Minaj for a misunderstanding on Twitter. She spoke outwardly about her mother’s cancer diagnosis to help fans going through a similar struggle strengthen their own resolve, contributing to their GoFundMe campaigns and meeting them backstage.

The rarified air in the upper echelon of artists who build decades-long careers is breathed by those who maintain a creative genius while actively managing their brands as CEOs. Bono is like this. Mick Jagger is like this. Madonna and Shawn Carter run companies that reach much further than their art. And Taylor Swift has the best business instincts of her generation. Her op-ed piece in the Wall Street Journal in defense of the album portended a hard line stance against free streaming and in support of indie artists that substantially shifted the music industry landscape almost overnight. Her open letter of protest to Apple — the largest company on the planet — prompted an immediate change in policy from the company, which acquiesced to her demand that artists be paid royalties for the three month free trial period of Apple’s streaming service. Her success triggered a similar stance by the two other biggest releases of the year: Adele and Coldplay, the former of whom just used this momentum to sell more albums in the first week of release than any artist in recorded history.

Taylor’s ingenious use of Twitter, Instagram, Tumblr and YouTube has been well documented. But her body of work as a whole in social media in 2015 was about more than just fan selfies (though she certainly set a record). She has wholly redefined the artist-fan relationship, deftly walking the line between controlling the message and empowering her legions of fans to speak with her voice. Her fans invented the phrase “Taylurking” referring to her random likes/retweets/reposts/responses to fans posting about her online. She wrapped and delivered holiday presents to groups of fans. She showed up at a bridal shower. She invited fans to her houses for a listening party. She has reset the norm for our expectations around access to the artists we love.

In historical context, there are only three years that can rival what we saw Taylor do in 2015: Elvis Presley’s 1956, the Beatles 1964, and Michael Jackson’s 1983.

Elvis Presley’s 1956

In 1956, Elvis became the King. In broad strokes, he unleashed the pent up sexual energy of post-war America. He became the world’s first rockstar. His self-titled album became the first rock and roll album to reach number 1. He played the Ed Sullivan show to 60 million people, which was 83% of the television audience at the time.

Elvis’ leg gyrations caused such consternation that television cameras only shot him from the waist up. His crowds at concerts caused such intense screaming and chaos by fans that he was reported to J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI as a threat to national security. He invented the practice of rockstars signing fans’ body parts.

He signed a multi-film deal, and released Love Me Tender at the box office. He put more songs in the Top 100 in 1956 than any artist since records had been charted. He also set the model for artists to build businesses off of their brands; he became a merchandising powerhouse, selling $22 million in Elvis goods that year alone. Elvis made an unprecedented transformative commercial and cultural impact on America in 1956, setting the stage for every other year on this list.

If there is a critique of Elvis’ 1956, it’s that his body of work was almost exclusively confined to America. But this holds little weight when looking at the actual distribution and transportation methods available to him at the time. Given the logistical and travel constraints of the day, his 135 show tour of the U.S. in 1956, from high schools to hayrides to the Gator Bowl and Cotton Bowl, remains a superhuman feat no modern artist would dare take on.

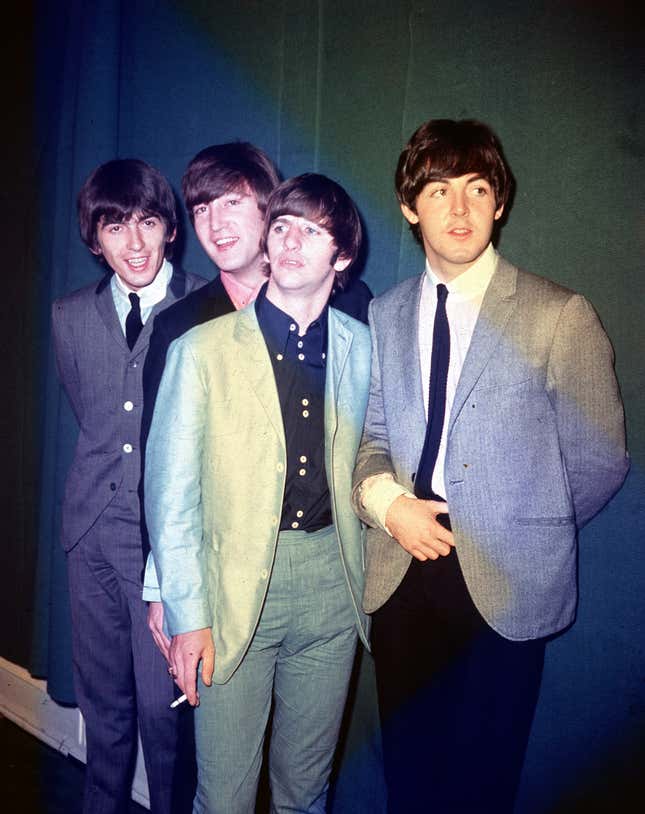

The Beatles’ 1964

While they had blown up in the UK in 1963, in 1964 the Beatles took over America and the world. They played live on the Ed Sullivan show to 34% of the population of the United States (73 million people). They became movie stars; their movie “Hard Day’s Night” debuted in July to critical acclaim, where they were compared to the Marx Brothers.

In April, the Beatles held twelve positions on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart, including the top five. They played 37 shows in 27 days across Europe, Australia and Asia. They then came back to the States and played 30 shows in 23 cities in less than a month to 10,000–20,000 people each (albeit lasting only 30 minutes each). They would have toured more and to larger crowds, but the amplification technology at the time simply could not out scream their legions of fans, and they chose not to subject fans to such an inadequate sonic experience.

Their hairdo had a larger impact on youth culture than the Mohawk or Jen Aniston could ever have dreamed. They met Bob Dylan in a hotel room, who introduced them to weed. The meeting is widely regarded as the reason he picked up the electric guitar (at the time, this was the equivalent of Adele releasing a rap album).

What is even more incredible about their 1964 is the period that immediately followed it. The Beatles, by any stretch, submitted the finest five years of recorded music output in the history of any musical artist/group from 1965–1969: Rubber Soul (1965), Revolver (1966), Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), The White Album (1968), and Abbey Road (1969). This is a finer catalogue than most of their contemporaries or predecessors entire career, in the time it takes most artists to release two albums. (For example U2’s The Joshua Tree and Achtung Baby,two of the most critically acclaimed albums of their generation, were released five years apart.) The Beatles cemented their position as the influencers of the century of music that followed, and as if that wasn’t enough, they broke their peers. The Sgt. Pepper album is widely attributed with causing Brian Wilson — then the leader of The Beach Boys and, in their eyes, their primary musical competitor — to have a complete mental breakdown upon hearing its brilliance.

Michael Jackson’s 1983

Thriller was released in late 1982, but the year it exploded was 1983. It topped the Billboard 200 chart for 37 weeks, and was the first album to have 7 top 10 singles. The album is the greatest selling album of all time, with over 30 million copies sold. It mopped up Grammys, AMAs, and the rest of the lot of awards by the armfuls, including Album of the Year. He released the Thriller video, which not only paved the way for the video as an artistic format, MTV, and the general visual importance of musicians, but was deemed by the Library of Congress as a work of enduring importance to American culture that should be preserved for all time.

In March, he performed to 47 million people on a show celebrating the 25th anniversary of Motown, reuniting with the Jackson 5. Seizing the moment, he then delivered his iconic solo performance of Billie Jean, wearing a sequined and rhinestone one-gloved getup, debuting the moonwalk, and sending the world into orbit with him.

1983 was also a landmark year in Jackson’s impact on the business of music. He negotiated the highest royalty rate in the business. In November, he paved the way for a significant part of the future of artists’ income by signing a $5 million endorsement deal with Pepsi. He effectively made it cool for musicians to pimp brands.

Also that year, Jackson began investing in the publishing rights of other artists, seeing the value of copyright ownership long before any of his peers, and ultimately paving the way for his ownership of the majority of the Beatles’ catalogue. And yet, the major asterisk forever emblazoned on this year: Michael didn’t tour. Touring was always his Achilles heel, and it ultimately led to his untimely death in 2009. Still, in terms of cultural significance, 1983 was the year we crowned the King of Pop.

Where to from Here?

So that’s the company Taylor Swift keeps as we head into 2016. Perhaps the most interesting question now is how she will possibly top what she’s just done. What else is left? What if, as Jack Nicholson once said, this is as good as it gets?

There’s good news in this regard: from a similar apex, her peers in this analysis all delivered creative and cultural highlights that live on today. But each artist had personal and career stumbles too. Elvis got fat, the Beatles broke up, and MJ got just plain weird. There is a cost to greatness; the impact of such global achievement and fame weighs heavily on the human psyche.

Perhaps most impressive about Taylor’s 2015 was that despite her ascendance, she managed to remain incontrovertibly human. Let us remember this. It is this humanness that will steel her for the inevitable occasional missteps her life will bring from here. If she can navigate them as they come, we may look back on that achievement as her greatest of all.

A version of this post originally appeared on Medium.