There was no pizza in Nairobi. No good pizza, at least.

That struck Ritesh Doshi as odd during a visit home in 2010. It bothered him enough that the investment banker decided to leave London the following year and move to Kenya’s capital city and do something about it. In November, he set up the first East African franchise store of US-based Naked Pizza.

He sold his apartments in London and Nairobi for the half-million dollar initial investment. Two more stores are planned this year, two more next year.

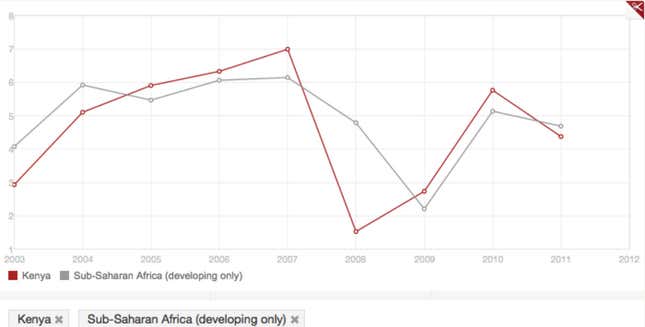

Investments like his are riding on today’s election. Kenya is one of Africa’s fastest growing economies, but it knows all too well how quickly fortunes can reverse. 2007 was the year of the last general elections, which turned violent and deadly. More than 1,200 people died, about 600,000 people were displaced. And foreign direct investment plummeted that year from a record $729 million to $95.6 million in 2008, a staggering 87% drop.

So why did Doshi take the plunge, just five months before elections also fraught with political tension?

“My view is that I wanted to be here,” says Doshi. “A lot of people told me to wait till after the elections. From a business perspective, I wanted to have an advantage. I think everyone is going to want to be here after the elections. I believe in Kenya and I believe in the opportunity.”

Today’s highly charged contest takes place under the new constitution, adopted in 2010. The two front-runners for president are the current Prime Minister Raila Odinga and Deputy Prime Minister Uhuru Kenyatta, both facing a dead heat in the polls. If neither candidate emerges a decisive winner, Kenya will hold a runoff election on April 11.

The stakes are high for both candidates—and the country’s business climate. Last time around, the post-election violence in 2008 broke out after Odinga claimed to be cheated of victory by supporters of the incumbent President Mwai Kibaki. Following a process of mediation brokered by former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, Odinga joined the government of national unity. In turn, Kenyatta, the son of Kenya’s founding president, is facing trial at the International Criminal Tribunal (ICC) in the Hague for allegedly orchestrating some of the violence. He denies the charges.

Among a new breed of foreign-educated entrepreneurs returning home, Doshi is pragmatic about the tumult caused by political uncertainty. But he believes the economic potential—Kenya’s growing middle class, increased disposable incomes, and corresponding desire to upgrade living standards—outweighs risk.

He’s staying in Nairobi through the elections, but a lot of people have left the country or sent their families away. “I can see the impact in my sales. This Friday our sales were down 30% on what we would usually do on a Friday,” he says. “Many people have taken flight—but I think it is unfounded.”