No matter how close a health care center comes to resembling a spa, or how well a hospital room imitates a hotel suite, its primary job is to heal, not pamper. With the scarcity of health care dollars already preventing people from receiving access to basic care, it’s easy to look on hospitals’ pouring of money into design as unconscionable excess.

But while indulgence surely occurs for indulgence’s sake, numerous studies have established that the environment – its colors, sounds, and other design characteristics aside from its cleanliness — may have a direct influence on health and healing. Elements like artificial light and unwanted sounds have been linked to physical effects similar to those caused by stress, such as raised blood pressure, along with symptoms of depression. Natural light has been shown to have mood-elevating and pain-easing qualities; the presence of trees and nature appear to impact human health in subtle but measurable ways as well. Easing anxiety and creating a positive atmosphere for healing, it is argued, can lead to tangible outcomes.

“A revolution in the science of design is already under way,” according an article in last week’s New York Times’ Sunday Review. This is certainly the case in health care: the emerging field of “evidence-based design” aims to introduce elements of construction and atmosphere proven to promote healing.

The tactic is purely logical from a basic science perspective. Rugs, for instance, may be a bad choice for a space simply because carpeting houses more bacteria than bare floors.

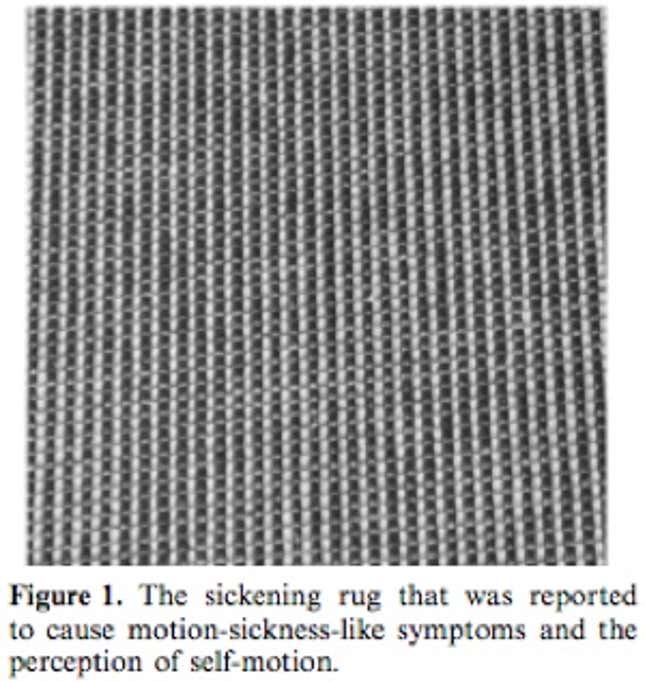

But a poorly chosen pattern for a rug can have negative effects, too. In the Times article, Lance Hosey notes that people are motivated by the color green, drawn to “golden rectangles,” and experience stress relief when faced with the “irregular, self-similar geometry” that often appears in nature. We could add that they do not, as a controlled experiment confirmed last year, respond well to static, repeating patterns. The authors had participants look at a black and white rug with such an aesthetic; after five minutes, “even neurologically normal individuals” were left with physical symptoms of motion sickness.

That’s more than enough evidence that this specific rug would not be the best carpeting choice for, say, a patient waiting room. Just as designers of Vegas casinos seek out disorienting floor patterns to keep patrons’ eyes on the slot machines, designers of hospitals and other health centers at the very least try to intuit choices that will lead to calming and relaxing effects.

But there is also a movement underway to draw upon cognitive and emotional processes, using a holistic approach to promote healing and recovery through the elements of a space. “It should come as no surprise that good design, often in very subtle ways, can have such dramatic effects,” Hosey continues. “If every designer understood more about the mathematics of attraction, the mechanics of affection, all design — from houses to cellphones to offices and cars — could both look good and be good for you.”

Hospitals, he leaves out, seem obvious places to try out such design tactics. Those that can afford to, like Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, are implementing such changes in droves.

Their cancer treatment center, for example, has the daunting challenge of being located underground. In its original inception, its designers just went with that theme, making the most of hard edges and industrial surfaces. In their thinking, it “reflected a ‘desconstructivist’ strategy aimed at providing comfort and confidence to patients by acknowledging the realities of fighting cancer.” In patients’ minds, however, it more closely resembled descending into a tomb. It wasn’t quite the “reality” anyone battling cancer wanted to reflect on during long sessions of chemotherapy.

The new incarnation of the center, completed in 2008, was the result of five years of patient input and careful attention to detail. Its designers tried to figure out how to use lighting and colors to make it “vibrant, energetic, comforting, and collarborative,” explained Dr. Robert Figlin, the center’s deputy director. They made up for the lack of natural sunlight with close approximations that patients are able to adjust, installed individual thermostats, and included an aquarium and nature-inspired artwork.

“We believe these elements of light, nature, warm, welcoming interiors, privacy, art, all contribute to the healing process,” said Zeke Triana, the Director of Facilities, Planning, Design and Construction for the health center’s campus, currently in the process of being redesigned as well. “I think those are basic human needs.”

The center reports high patient and staff satisfaction scores, but, as with the original design, the environment’s healing effects are more inferred than objectively measured. That may not be enough to justify the spending of health care dollars.

Design decisions that increase safety and reduce infection, of course, will save money. In cases where holistic advantages have been shown to complement measurable health outcomes, such efforts are easier to rationalize. For example, it was first noted in 1920, in the Journal of the American Medical Association,that keeping patients in private rooms helps keep infection from spreading. It also makes it easier for doctors and nurses to do their jobs. Most importantly, private rooms end up being more cost-efficient. But they also accommodate a patient’s social support network, and allow sensitive conversations to occur in privacy. And by reducing noise and traffic, they’re believed to ease a patient’s stress. While such outcomes might be a hard sell as the primary justification for using private rooms, studies have supported all of these theories.

In 2006, the American Institute of Architects developed structural guidelines for hospitals that focuses on the effect of elements of the environment — like poor lighting or inadequate space — on patient safety. They too, stress the importance of backing any and all innovations in scientific evidence. When a design’s ambitions become loftier, suggesting, perhaps, that images of nature induce states of meditation that allow patients to somehow transcend their illness, its effectiveness is much more difficult to establish, as should perhaps be thought of more as an added bonus than an integral component of health care. But if we’re going to be moving toward more scientific design, as Hosey argues we should be, hospitals would be a great place to start.