With the beginning of the new year comes an unfortunate annual tradition. Each year, families purchase purebred dogs as short-sighted holiday gifts—many of which wind up in animal shelters in the first weeks of January.

Our predilection for purebred dogs is troubling for a number of reasons. For one thing, it seems unnecessary to spend hundreds or even thousands of dollars for a purebred when there are ample mutts available (for free) at shelters, ready to accompany a new family home. Worse yet: When we breed dogs, we do harm to the animals we love.

“Purebreds have a higher risk for disease in many instances,” Dr. Thomas Famula, a professor of animal science at the University of California, Davis, tells Quartz.

Famula published research on the prevalence of health problems among mixed-breed and purebred dogs in a 2013 issue of the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. He and his team found that while dogs collectively suffer from a list of genetic illnesses, purebreds are more likely to have disorders including cataracts, hypothyroidism, and a heart condition called dilated cardiomyopathy.

There are some practical reasons to buy a purebred dog: Icelandic sheepdogs are great at corralling sheep in a harsh winter climate, bloodhounds are excellent for finding corpses, Belgian Malinois work well assisting in military operations. But most Americans make the decision to buy purebred companions based on aesthetic preferences—often without regard for the associated diseases of a breed.

“Many people are willing to accept the risk [of disease] to get the dog they prefer,” says Famula. “The advantage of breeds is being able to predict the future: future size, future color, future temperament, and yes, perhaps, future cause of death.”

Valuing aesthetics over ethics

It’s understandable that people may take a liking to a corgi’s short, stout legs or a basset hound’s floppy ears. But surely we would object if people were willing to gamble with their children’s health in order to ensure that they would grow an extra-long neck like a dachshund’s, or have much looser skin like the St. Bernard. This is especially true when such traits serve no practical purpose.

Consider pugs, French bulldogs, and other brachycephalic breeds (pups with punched-in looking faces). Sure, they seem cute and silly with their bug eyes and tongues too big for smiling mouths. But in breeding these dogs to make them resemble human babies, we’ve made them prone to a cocktail of genetic defects. Many brachy dog owners can attest that their pets have trouble breathing when they get excited—with death as a potential consequence. Pugs’ shallow faces also make them vulnerable to proptosis—a condition in which their eyes can pop out of their sockets.

Other purebreds are equally at risk for a wide range of ailments.

“Dalmatians have a very high risk of hearing loss,” Dr. Famula tells Quartz. “Why? Because the color pattern of spots is associated with defects in melanocytes [the pigment responsible for skin color] that develop into the inner ear.”

In fact, Dr. Famula notes, selecting against deafness in dalmations would likely alter their signature color pattern. “And then where would you be?” he notes. “The whole reason for dalmatians is the spots. So you remove the ‘disease’ and remove what makes the breed a breed.”

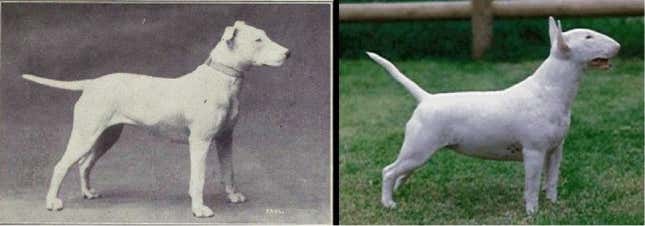

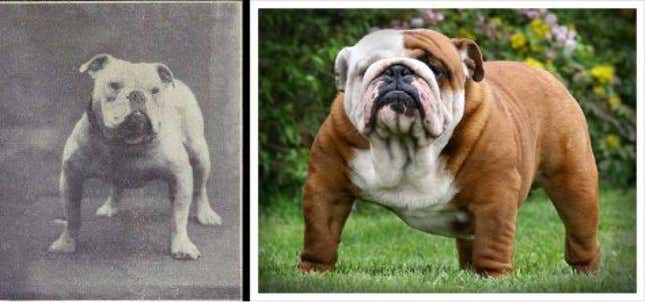

But what makes a breed a breed has never been set in stone. In 2012, Caen Elegans, author of the blog Dog Behavior Science, wrote an article showing side-by-side comparisons of dog breeds as we knew them 100 years ago, and as we know them today.

These comparisons handily demonstrate how dogs have been intentionally bred for exaggerated traits, with worrisome results. It’s clear that the vision and mobility of the modern bulldog above is severely reduced. In addition to having too many teeth for its mouth, the bull terrier suffers from compulsive tail-chasing, to the point that it interferes with their normal life. Breeders selected for aesthetic characteristics, rather than functional ones.

Mark Derr, author of How The Dog Became The Dog as well as numerous articles relating to the politics and morality of dog breeding, talked with Quartz about how this kind of genetic modification came to be the social norm.

“Favored sires are dogs known to win championships, and so are bred so often that their genes become disproportionately represented in the breed gene pool,” Derr says. “Inbreeding limits genetic diversity and enhances the possibility of a genetic ailment becoming fixed,” or the norm for a breed.

It’s important to note that inbreeding (a fact of purebred dogs, which are often bred with their parents, siblings, and cousins) does not necessarily cause illness. The culprit is homozygosity—the pairing of two identical versions of a gene on a given chromosome. But the chances of homozygosity are increased with inbreeding, making disease more likely.

Not only do we continue to support breeding dogs predisposed to certain illnesses, we continue to value aesthetics over ethics after puppies are born. It’s normal to declaw certain breeds, trim their ears and chop off their tails. (Boxers, Jack Russell terriers, rottweilers, and dobermans are among the many breeds affected.) This elective and unnecessary surgery exists only to serve arbitrary standards set by dog fancy groups, and puts the animals in a great deal of pain and at risk of infection.

As Elegans writes, “condemning a dog to a lifetime of suffering for the sake of looks is not an improvement; it is torture.”

It’s high time to call these practices out as animal cruelty.

The path to better breeding

One solution is for the American Kennel Club to alter its standards on what constitutes “perfection” in certain breeds, particularly those characteristics that are linked with genetic illness or mutilation. The aforementioned dalmatian is a great example. “Spots are round and well-defined, the more distinct the better,” the AKC instructs—omitting the fact that the more shapely the spots look, the higher the chances of having a deaf animal.

Another option is for breeders to do what the ASPCA recommends and take responsibility for the animals they’re creating by choosing not to perpetuate traits and practices that negatively affect the health of their animals. Breeders can select against making pugs’ eyes prone to popping out of their faces, and quit inbreeding entirely—thereby taking a firm stance against genetic illness.

The power lies with the public too. If pet owners are truly stuck on the idea of buying a purebred, and have exhausted searches with breed-specific rescues and shelters, the least they can do is take time to research ethical breeders. Dogs available online and in stores are likely products of puppy mills, which eagerly breed sick animals if it means turning a profit, and supporting them means perpetuating genetic illnesses.

Famula also believes in the power of data to reduce instances of inherited disease.

“There is no reason you can’t create a breed that is both attractive and healthy,” he says. “If pure breeders were open with one another, and shared phenotypic information with one another, they really could keep all they love in their breed while reducing the risk of disease.”

As a consultant with Guide Dogs for the Blind, which breeds around 1,000 puppies a year, Famula has found that it’s possible to catalogue dogs’ genetic information and avoid breeding animals that might pass diseases onto the next generation. But he notes that it’s hard for amateur breeders and pet owners to access such sophisticated statistics. That’s why pet owners stick with breeds, he says: “That is the only data they can count on.”

Discontinuing the practice of breeding dogs altogether is also an option.

“We should stop breeding dogs if the alternative is continuing to produce animals with known defects,” Derr says. “Breeds that cannot be made healthy should not be bred. Anything else is cruel. If a general moratorium on breeding is needed to achieve that, we should have it.”