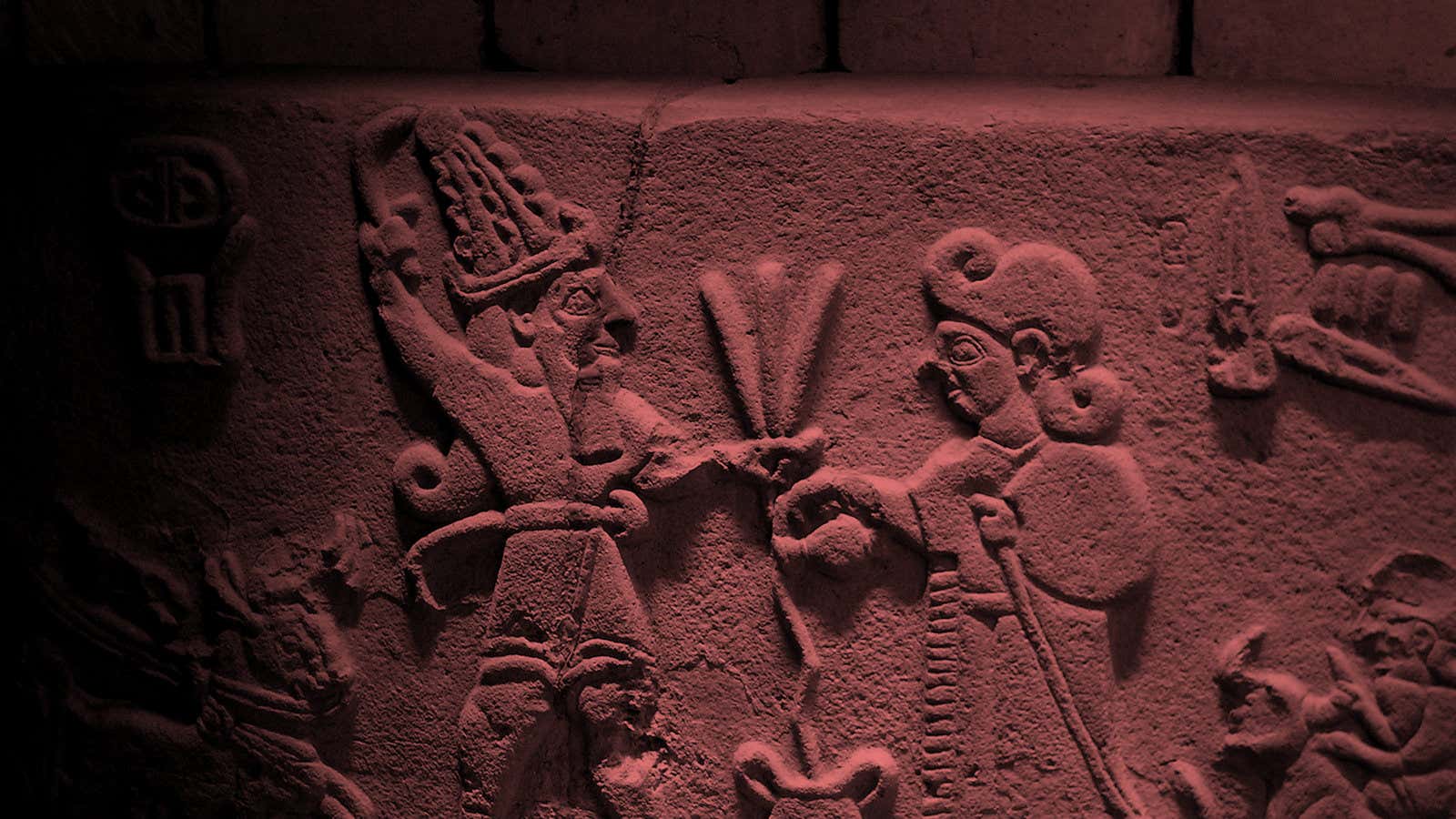

The year 1177 BCE roughly demarks the disintegration of humanity’s first global civilization: the Late Bronze Age. At its peak, a booming trade in raw materials, agricultural goods, and finished products—from jewelry to pottery, spices and wine—encircled the Mediterranean and stretched north, perhaps as far as present-day Scandinavia, and east to Afghanistan and India.

Then, after centuries of brilliance, the civilized world of the Bronze Age came to an abrupt and cataclysmic end.

The Bronze Age cultures surrounding the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas—including what is now modern day Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Iraq, and Iran—formed a complex, highly interdependent system. Archaeologists continue to argue about the key triggers of its demise. And indeed, there were multiple interrelated failures.

In recent years, however, scientists have begun to assemble an increasingly compelling picture of how the Bronze Age unraveled and collapsed. Kings called for emergency shipments of grain from other countries as the climate grew more arid; drought and then famine stalked the land. The “Sea Peoples” invaded and plundered coastal cities. Were they hungry environmental refugees, or the ISIL of their time? Perhaps both?

While the specific details are difficult to reconstruct, we know how the story ends. The many kingdoms around the Mediterranean fell like dominoes in just a few decades. Their thriving economies and cultures disappeared, as did their writing systems, technology, and monumental architecture.

Fast forward to the year 2007 CE, which marked the beginning of the worst long-term drought Syria has seen in modern history. In 2008, three quarters of area farmers saw complete crop failure and herders lost some 85% of their livestock. In 2009, the United Nations reported that more than 800,000 Syrians had lost their entire livelihoods because of the drought. The UN estimated that by 2011, two to three million Syrians had been driven into extreme poverty.

Displaced farmers, herders, and their families migrated to urban areas in search of jobs and food, living in tents along roads and around cities, straining urban infrastructure. A government unresponsive to the developing humanitarian crisis fostered rebellions, which began in Daraa, spread to Raqqa and Hassakah, and in time devolved into today’s civil war. Yes, it’s climate change, beyond a doubt by now, but there’s also a long history of government mismanagement and misguided policy at work.

Syria is not alone. Some combination of climate warming, expanding population, over-exploitation of shrinking water resources, and antiquated approaches to agriculture is undermining stability in country after country around the Mediterranean Basin. Worse yet, even a subset of such woes can begin a death-spiral for local agriculture, closing off the possibility of return to the land when conflict ceases.

We see the current migrants from the Middle East (and Africa) as political refugees. And they are, of course. But they’re more fundamentally environmental refugees, fleeing lands that can no longer support them without profound changes in how land and water are managed.

We don’t know how this story ends or how the world will look in, say, 2077. What we do know is that we, unlike the denizens of the Bronze Age, understand both what’s coming and what to do about it, at least in a technical sense.

Science, particularly chemistry and genetics, and technology have enabled enormous strides in agricultural productivity. Indeed, without fertilizers, better seeds, and tractors, our population could not have grown from a largely rural one billion, where it stood when Malthus told us we were forever doomed to famine, to today’s largely urban seven billion—even as we halved the fraction of us experiencing chronic hunger.

There’s much yet to be learned about how to produce food under the new climatic conditions, even as we seek to coax more from less land more sustainably. But the genomic and technological revolutions of the late 20th century have provided the critical tools. We will need to modify organisms genetically to thrive in the new climate on less land and water. We will need increasingly sophisticated, GPS-guided machinery to maximize yields while minimizing environmental pollution.

All of this is possible. But at the same time, we see a growing aversion to science and technology in the developed world. Both genetic modification (GM) and technologically sophisticated farming (aka factory farming) are widely vilified, while old-fashioned “organic” farming methods are romanticized. There’s room for both, but there’s also little doubt that we’ll need more science, not less, if we’re to meet the needs of a still-growing human population.

Perhaps the deeper and more immediate issue is how we will manage the integration of millions of refugees, including those who once farmed the land in Syria, now fleeing persecution and starvation. The challenge today is to feed, support, and socially integrate people of very different belief systems into a globalized society in the face of growing environmental stress.

The Bronze Age world collapsed. Will ours?