Debi Durham is a familiar type in America’s state capitals, if a species under threat in Washington DC—a Republican policymaker guided by practicality, not ideology. The longtime head of an Iowa business association, Durham has spent the past five years as head of the Iowa Economic Development Authority, where she’s talking about a very different set of challenges and opportunities than the two Republican frontrunners trying to kick off their path to the White House with a win next week in Iowa.

Durham was appointed to her post by Republican governor Terry Branstad in 2011. Branstad is the longest-serving governor in US history—from 1983 to 1999 and again since 2011—but he’s probably more famous now for having flatly told reporters that Iowans shouldn’t vote for senator Ted Cruz in the state’s upcoming caucuses, which will be held Feb. 1.

His reasoning? Cruz opposes the renewable fuel standard set by the Environmental Protection Agency, which requires that a certain share of fuel used in cars, planes, and heating systems be derived from renewable sources—including ethanol, the corn-derived fuel that is a touchstone of Iowa’s political economy.

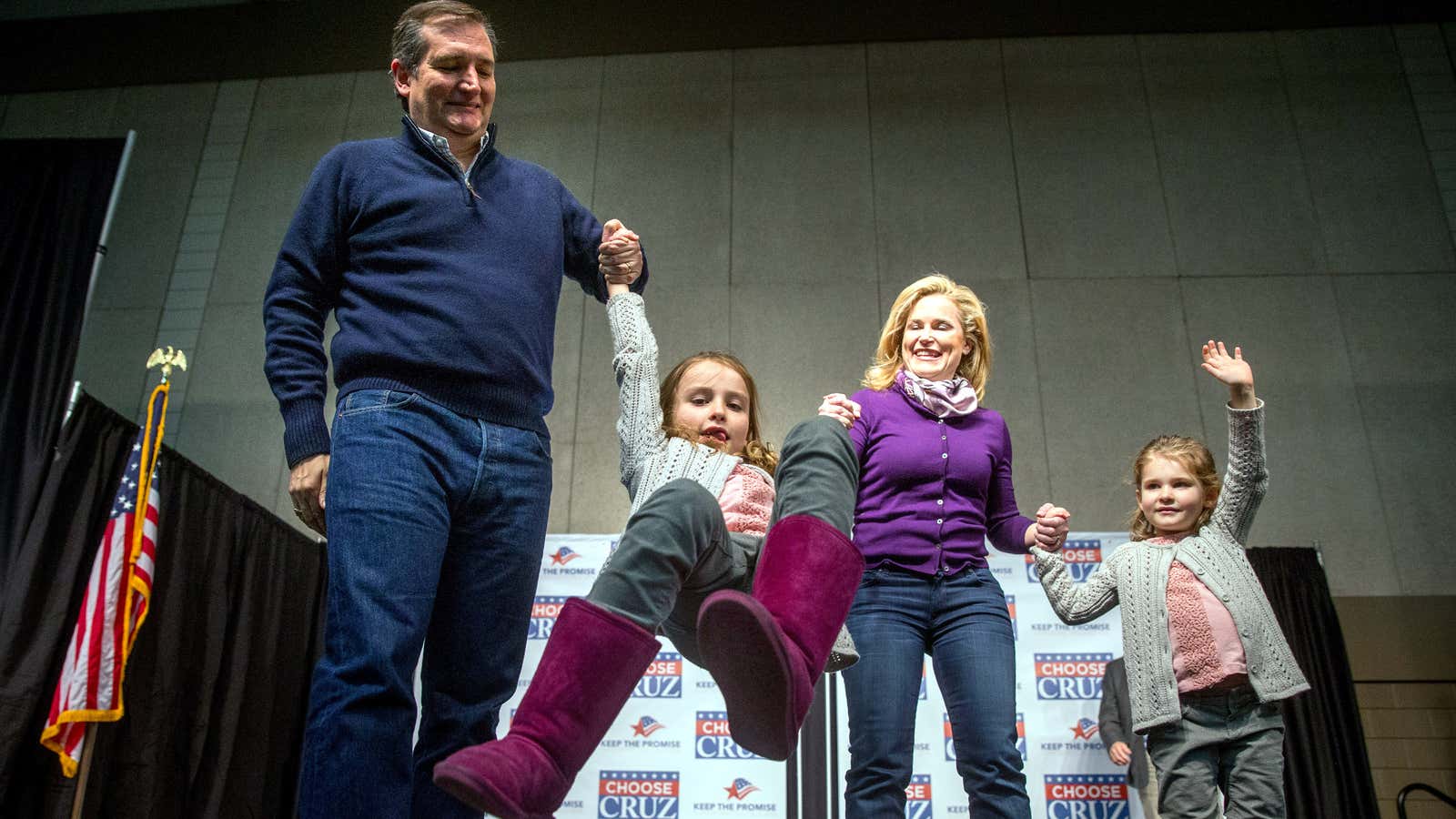

Cruz argues that his opposition would actually create a bigger market for ethanol. But either way, in Iowa—where the government’s nurturing of the ethanol industry is largely seen as an economic success story—Cruz’s desire to see the fuel standard (effectively a government subsidy) dismantled represents the cognitive disconnect in this Republican election. On the one hand are the modern party’s centrist and business-leaning wings, and on the other its more radically conservative, shrink-the-government-down-to-nothing voters.

Cruz, of course, made a name for himself as the Tea Party’s senator, blowing up compromises in the name of his anti-government principles. And now, the Republican establishment fears that his election would definitively crack the alliance between the two wings of the party, forged in a commitment to low taxes.

Branstad’s anti-endorsement of Cruz was seen as giving a boost to frontrunner Donald Trump, who, ever the dealmaker, has taken the opposite tack: He says that the amount of ethanol in US gasoline should be increased.

State and federal support for ethanol is controversial across the political spectrum. Some environmental advocates warn that certain ethanol manufacturing methods aren’t much better than fossil fuel, while free-marketeers (and oil companies) resent the government’s helping hand.

For Branstad, Durham, and other Iowa Republicans, ethanol and the government’s role in generating a market for it has been a crucial win—the ethanol industry in Iowa is thriving, even as more direct subsidies in the form of ethanol tax credits, in Iowa and nationally, have expired in recent years. Durham’s agency says the subsidies have more than paid back the state in increased economic activity and jobs.

“Was that value added for the state of Iowa? Were there incentives that we put in? Did it give the taxpayers the return on investment? The answer is yes,” Durham tells Quartz. ”We are no longer investing in that platform for a variety of reasons; we have to work constantly for new technology. I am not a believer that you subsidize an industry forever.”

Durham’s new plan is to expand on the success of the biofuels initiative with tax credits to build its biochemicals industry, a $250 billion domestic market which could draw on Iowa’s existing raw materials and workforce. By luring in companies with tax breaks, Durham hopes that the another modern sector will take root in Iowa—where the unemployment rate is 3.4% and, Durham is at pains to note, only 7% of annual GDP comes from agricultural work.

There are a few other items on Durham’s to-do list, including working with Iowa businesses to attract new immigrants, including guest-workers, to the state, and promoting exports and free trade deals, like the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Neither policy has found any traction in the Republican debate, but both are key priorities for Iowa’s Republican government.

All of this is why the party’s donors and leaders are taking a long second look at Trump, a man who they think at the very least understands business. And yet the party’s calcified intellectuals—not all friends of Cruz—fear that Trump has no principles whatsoever, and will make an even worse alternative. While Democrats in an increasingly heated primary are being asked mostly to choose between their heads and their hearts, the Republican rupture is over whether “nothing”—that is, the gospel of limited government—is enough to offer businesses and workers in the modern global economy.

In Iowa, voters are looking for answers. Durham isn’t publicly backing a candidate yet, but offered a hint as to how she’ll decide who to support.

“I need a candidate that can actually talk about the future,” Durham told Quartz. “I need people to talk about how we make the nation more competitive with our income tax rates, with all this money sitting offshore, [to] unite on a message, and not take the conversation down to a weak common denominator. Not just in sound bites, but actually a plan on how to do that.”