Dr. Malcolm Potts has spent the past half-decade pioneering the field of family planning, and he’s on the verge of making birth control pills as easy to buy as aspirin.

This January, the 81-year-old public health professor’s five-person company, Pelagius, bought the rights to an existing prescription oral contraceptive—the first big step in bringing “the pill” out from behind the counter and into the aisles of drug stores in the US.

“There will be three groups of women who benefit,” Potts, who served as the first medical director for The International Planned Parenthood Federation in the 1970s, told Quartz.

“Professional women who go on vacation and forget the pill, women who use physical contraceptives because they think the pill is dangerous, and the third group is women without health insurance or who are not registered citizens—and they do want to plan families,” Potts said.

Potts, who teaches at the University of California, Berkeley, sees making the pill available over-the-counter as a public health imperative. Although birth control is relatively inexpensive, the barrier of a prescription still stands in the way of many women in the US. Currently, over 50% of pregnancies in the country are accidental. Increasing access to birth control, Potts believes, will have a direct effect on this number and, in turn, reduce the number of abortions performed in America.

Medical societies such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Medical Association have endorsed the switch from prescription to over-the-counter, but the FDA can’t just decree any pill to be sold over-the-counter. Rather, a company must come to the FDA for approval. The approval process then takes an average of three years. (Potts estimates Pelagius’ pill will be available over-the-counter by 2019, if all goes as planned.)

“I thought you could go to the FDA with some generic drug and say ‘Hey, can we sell this?’” Potts said. “When I looked into the process, I realized that was not the case.”

Potts and his colleague Dr. Nap Hosang, who is also a professor of public health at Berkeley, approached Samantha Miller, a pharmaceutical entrepreneur, in 2014 and asked her to help them acquire the rights to a pill.

“When Malcolm came to me, I didn’t realize that so many pregnancies in the US are accidental, and that it’s concentrated among women who have less resources and who don’t have a husband,” Miller said. “The more I thought about it, the more I realized this is a huge issue for women’s rights and for fighting poverty.”

Miller agreed to help, and in a fortuitous turn of events, she found an established pharmaceutical company that was willing to sell the rights to a birth control pill—an extremely rare occurrence, Miller told Quartz.

“I’ve been in the pharmaceutical industry for 25 years, and no one has made a deal like this that I know of,” Miller said. “The bottom line is that women’s health and contraception is not a priority for the pharmaceutical industry. They are interested in oncology drugs and drugs for rare diseases—drugs where they can have exclusivity.”

Oral contraception is a mature market. Pharmaceutical companies have tinkered with different formulations of the pill and have a good understanding of exactly how much estrogen is needed to prevent pregnancy without harming a woman’s health or comfort.

“Data says 80% of women do well with 30 micrograms of estrogen,” Miller said. “So we wanted a pill with about that much estrogen that also had decades of safety data.”

The pill Miller found has both. Although she cannot disclose the name of the pill or the pharmaceutical company from which Pelagius bought it, she did say that it is one of the pills currently on the mainstream market.

“We got just the pill that we wanted,” she told Quartz.

The next step for Miller and Potts is to submit the pill to the FDA for approval. Over thirty years of data exists from studies on the safety and efficacy of the pill, which, according to Miller, means they have a pretty good shot at getting a go-ahead from the FDA.

A landmark study published in 2010 regarding the safety of oral contraceptives will help Pelagius’s case, Miller said. The study includes 39 years of data on over 46,000 women in the UK who took oral contraception at some point in their lives. It found that this type of birth control actually reduced the women’s risk of death by cancer and heart disease.

“There’s never been a case of an overdose. You can’t commit suicide with it, and you can’t become addicted to it,” Potts said of oral contraception.

While this is true, the health risk of making the pill available without prescription is the danger it poses to women who smoke. Smokers who take oral contraceptives are at a higher risk of developing hypertension, which can lead to heart failure.

“The complicated question that hasn’t been answered by the studies is ‘Can a woman who buys this over-the-counter make sophisticated decisions?’ Will women who smoke make the right decision to not take it?” Potts explained.

In order to present their pill to the FDA, Pelagius has to commission a study that will test for this, called a “real use” study. The study, which Pelagius plans to outsource to a research firm, will consist of providing packets containing the birth control and sophisticated instructions pertaining to who should and should not use it to a random sample of women, consisting of both smokers and non-smokers. The researchers will then determine what percentage of the women complied with the instructions, as relates totheir smoker status.

If the study is a success, Pelagius will be at the threshold of achieving one of the biggest victories in family planning history.

In addition to making the pill available over-the-counter, Pelagius aims to make the pill extremely affordable. To do this, Potts and Miller have organized the company as a benefit corporation, or B corp. B corps are a relatively new category of for-profit companies that receive tax-breaks for incorporating a social mission into their bottom line.

“Our goal is to be low cost—low cost manufacturing and low cost marketing,” Miller said. “Our double bottom line is making this accessible and affordable for all women.”

Miller is also building a case to present to insurance companies to convince them to reimburse women for the purchase of the pill.

“Our argument is ‘Would you rather pay $20 a month for birth control or pay for an unintended birth?’ We think that insurers will see the financial logic in this,” she said.

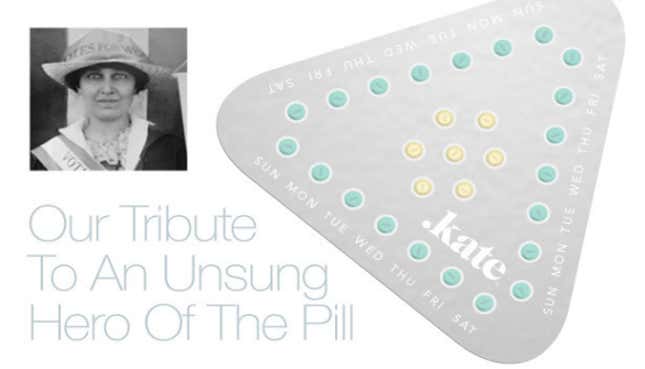

The Pelagius team has decided to name their pill “Kate”—after Kate McCormick, a biologist and suffragist who gave much of her family fortune to fund the development of the first birth control pill. Fittingly, Miller, Potts, and Hosang have funded Pelagius with their own money so far.

Now that they’ve succeeded in acquiring the rights to a pill, they plan to take their fundraising efforts public with a crowdfunding campaign. Miller and her team have prepared a landing page to publicize the campaign, which Miller said will launch sometime in the next few months. Pelagius will use #liberatethepill as a rallying call online.

Over nine million women currently take oral contraception in the US. If even a fraction of them give a dollar, they could make birth control available to women without access to healthcare, as well as save themselves a trip to the doctor.

“It’s an extraordinary privilege to be part of this process,” Potts said. “I hope that I live long enough to see its success.”