Italy’s economy is shrinking more than anyone realized—and that’s only going to get worse

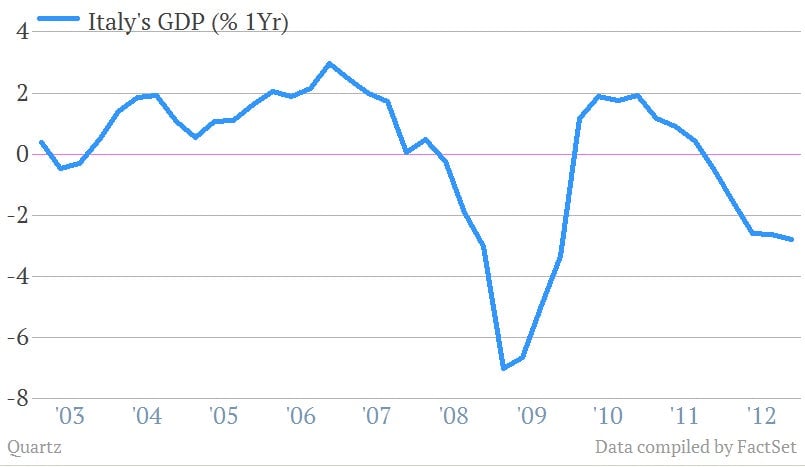

When does “unexpectedly bad” start being “expected”? Italy’s revision to its fourth-quarter GDP put that question to the test once again, as the economy contracted 2.8% year-on-year, compared to the 2.7% that was “expected.” Markit Economics attributed the slide, which marked a 0.9% quarter-on-quarter contraction, to “weak domestic demand.” Here’s a look at the year-on-year trend:

When does “unexpectedly bad” start being “expected”? Italy’s revision to its fourth-quarter GDP put that question to the test once again, as the economy contracted 2.8% year-on-year, compared to the 2.7% that was “expected.” Markit Economics attributed the slide, which marked a 0.9% quarter-on-quarter contraction, to “weak domestic demand.” Here’s a look at the year-on-year trend:

So the contraction was worse than economists expected—but given the growing preponderance of bad news about Italy’s economy, it wasn’t precisely surprising either.

The credit downgrade from Fitch on Friday highlighted the shaky state of Italian politics, and the growing obstacles to the reforms the country desperately needs before its economy can grow.

Earlier today, the yields on Italy’s 10-year benchmark bond hit 4.65%, up 7 basis points—putting them near Spanish bond-yield territory. And still RBS analysts had this to say: ”Credit markets continue to underestimate the risk of political instability in Italy and in the periphery, and the calls for a switch from a pro-austerity fiscal compact to a growth compact.”

As we pointed out last week, Italy is spinning beyond the control of European Central Bank monetary remedy, as borrowing rates for small businesses continue to climb. This is something ECB vice president Vitor Constancio called out in a speech today, when he said that “market fragmentation is severely disrupting” the effectiveness of the ECB’s monetary policy.

“In some countries, changes in our main interest rate are being passed on fully by banks; in others, because bank funding is tight, interest rate changes are being passed on hardly at all,” said Constancio. “This is making credit very hard to come by or unduly expensive in some parts of the euro area.”

Yep. And taken alongside Italy’s political gridlock, we should continue to expect the unexpected—unexpectedly bad, that is.