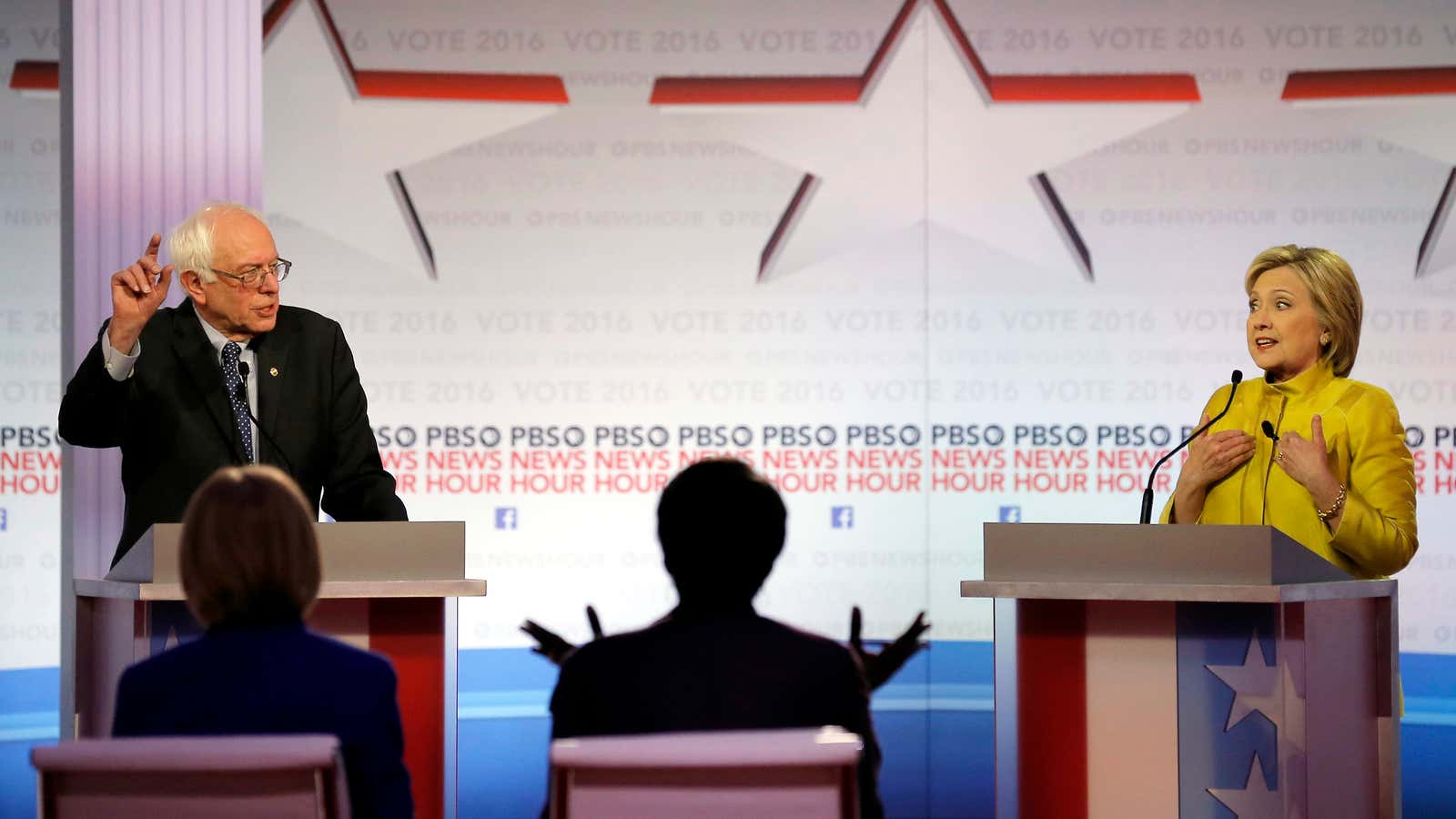

On the debate stage in Wisconsin last night, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders was betrayed by an old friend: Karl Marx.

No, it wasn’t due to fear-mongering about socialism—Democrats have heard president Barack Obama called a socialist often enough that it doesn’t appear to bother them much anymore.

Instead, Sanders got tripped up on the Marxist conviction that racism is solely a function of economic factors. At one point he was asked if race relations would improve under his presidency compared to the administration of Barack Obama. He replied:

Absolutely! Because what we will do is say, instead of giving tax breaks to billionaires, we are going to create millions of jobs for low-income kids so they’re not hanging out on street corners. We’re going to make sure that those kids stay in school or are able to get a college education. And I think when you give low-income kids—African-American, white, Latino kids—the opportunities to get their lives together, they are not going to end up in jail. They’re going to end up in the productive economy, which is where we want them.

Answering every question with a pivot to billionaires isn’t unusual for Sanders, but in the case of race relations, it is telling. In socialist theory, racism isn’t a true societal problem—instead, capitalism is the root cause. Race is just one more way for the ruling class to prevent workers from uniting by erecting false barriers between them.

Socialists say that this critique is reductive. After all, socialism is anti-racist—indeed, Martin Luther King, Jr. has been called a democratic socialist—but there are still long-standing tensions on the left between those who see racism as an economic phenomenon and those who identify more deep-set societal problem. While the Sanders website notes the importance of fighting “societal racism,” his public rhetoric often doesn’t include similar nuance.

As Sanders spoke, Iman Gandi, a legal analyst who works on reproductive health issues, tweeted that Sandra Bland, a Texas woman who died in police custody after being pulled over for a moving violation, “HAD a goddamn job. She still ended up dead. Jobs is not the solution.” You can see the same concern in Ta-Nehisi Coates’ disappointment with Sanders’ rejection of reparations (though it isn’t preventing Coates from vowing to vote for the senator).

Hillary Clinton doesn’t see race—or gender, or sexual identity—as a purely economic problem. The former secretary of State her closing statement to exploit the distinction:

Yes, does Wall Street and big financial interests, along with drug companies, insurance companies, big oil, all of it, have too much influence? You’re right. But if we were to stop that tomorrow, we would still have the indifference, the negligence that we saw in Flint. We would still have racism holding people back.

Clinton’s candidacy essentially rests on whether minority voters and particularly black votes in South Carolina, the next democratic primary, will support her.

Yesterday, she announced the endorsement of the Congressional Black Caucus’ political action committee next to civil rights icon Rep. John Lewis. But she has also been tarred with harsh criticisms of her husband’s term in office, which saw crime and welfare reforms with costs that fell squarely on minority communities—though we should note that the income gap between blacks and whites shrunk significantly at the time.

Now, her campaign is hoping that her acknowledgment of racism as a reality—rather than just a side-effect of economics—will resonate with voters who must live that experience daily.