Senator Bernie Sanders is suffering from a wonk gap.

His sweeping plans to reorganize the government to provide single-payer healthcare, free public college, and tax the wealthy have inspired his followers, but his campaign doesn’t have many details. His staffers say this doesn’t matter during the primary season and answers will come later, but it may be harder to make it past Hillary Clinton if voters aren’t convinced he can fulfill his plans.

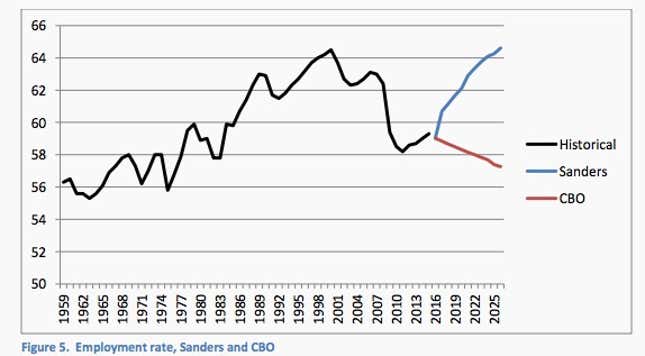

One study (pdf) of Sanders’ plans, produced by economist Gerald Friedman and touted by the campaign, relies on dubious assumptions, including 4.5% GDP growth over the first decade of his administration, more than doubling existing labor productivity, and returning labor force participation to 1999 levels:

This led to some wonk-on-wonk violence, as four former White House economic advisers (all of whom served under Barack Obama or Bill Clinton) released a scathing letter that concludes “much as we wish it were so, no credible economic research supports economic impacts of these magnitudes.” The former advisers also noted that promises like this will undermine the long-cherished Democratic tradition of pointing out that Republican economic plans are total fantasy.

Don’t ask, don’t tell

While the Sanders campaign frequently cites a list of 13o supporters (pdf) of its health and economic plans, the campaign itself has few experts on staff developing or defending its economic plans.

That reflects the campaign’s surprising evolution from an effort to merely elevate Sanders’ ideas within the party to becoming a bona fide contender for its nomination. But Sanders policy director Warren Gunnels brushed aside questions about whether Sanders’ plans are far more costly than he implies on the campaign trail.

When pressed on the assumptions behind Friedman’s analysis, Gunnels accused the former White House economists of trying “to paint us with a broad brush about what one economist has come up with in terms of estimates. It does scream of desperation. That is not a study from Senator Sander’s campaign.”

But did the campaign have any specific responses to the questions about how its plans will affect American workers?

“Of course, it’s not surprising that some of the same establishment economists who told us who wonderful NAFTA was, how wonderful permanent normal trade relations with China would be, how many jobs would be created with unfettered free trade, are now attacking Senator Bernie Sanders’ economic agenda,” Gunnels said.

The inescapable establishment

This is, in many ways, the Sanders trump card: whatever the critique, it’s the critic’s associations that matter most. If criticism comes from mainstream Democrats, who argue that the US can benefit from global trade, Sanders only has to point to the government’s inability to fairly distribute gains from the new economy, even under a Democratic president in Barack Obama.

When left-wing politicians cite studies and academics, it’s by and large a way to signal to moderate voters that they can deliver on their promises. For 2016 Democratic primary voters—and a campaign premised on the idea that of luring new voters with a broad vision—the promises matter far more than the delivery, and Sanders’ efforts to push his party to the left with ideological litmus tests has so far found a welcome reception.

Gunnels asked me, “Do these establishment economists believe that increasing the minimum wage is going to hurt?” I noted that one, Alan Krueger, was behind important research demonstrating that minimum wage increases often benefit workers. “But he hasn’t endorsed a $15 minimum wage!” Gunnels replied. Krueger wrote last fall that a $15 minimum wage would be appropriate for high-wage cities, and that $12 an hour is a wise national goal.

It’s a similar story on health care policy, where the existence of other single-payer health programs in other countries is enough to dispel questions of how single-payer would work in the United States. Asked if the campaign had a responsibility to provide some details of how its plans would work, Gunnels said, “look at our stump speeches.”

Stumped

Sanders speeches rarely delve into programmatic detail, but when they do, it is interesting.

Last year, the senator promised to break up the largest banks within a year of becoming president, citing a specific feature of the Dodd-Frank law. Sanders promised to use the feature—which requires a majority vote of financial regulators—to downsize major financial institutions. But would it even be possible to appoint so many people favoring radical action through a conservative senate? Not likely.

This week, the odds got a little rosier when Neel Kashkari, the new president of the Minnesota Federal Reserve, said in a speech that he believed banks were too big to fail and must be broken up or reined in. Sanders’ team praised the comments—but Kashkari is a former Goldman Sachs banker who ran the 2008 bailout program That’s just the kind of revolving door appointee Sanders professes to dislike. Is he the type of candidate Sanders could appoint?

“Based on his record in the past, it wouldn’t have been somebody that Senator Sanders would appoint,” Gunnels said. “But it just goes to show, you have people in those positions that have now taken a look at the problems that we have…who agree with Senator Sanders.”

Another Goldman Sachs banker turned reform poster child is Gary Gensler, now advising the Clinton campaign. “Senator Sanders led the effort in opposition to Gary Gensler’s nomination,” Gunnels noted. “He will not be nominating Gary Gensler to anything.”

Why the critiques don’t matter to Sanders

If you count out the financial sector turncoats and establishment Democrats, who will Sanders appoint to key positions? Whoever he wants, at least according to his campaign. According to the logic of a political revolution, whatever obstacles have hamstrung Obama’s policy efforts—namely, a virulent Republican opposition—would be wiped away.

“If senator Sanders becomes president, I find it hard to believe that the Senate would be in Republican hands and the House would be in Republican hands,” Gunnels said. “It’s very hard to see the American people also voting no at the same time as they’re voting for Bernie Sanders, to vote for Republicans who want to cut Social Security and Medicare and provide tax breaks to millionaires.”

In that scenario, Gunnels would expect Democrats to overcome the filibuster and use simple majority votes to appoint Senator Sanders’ nominees. But such expectations may not match the reality of the US political process, which as recently as 2012 generated a divided government with a decidedly liberal president and a firmly conservative congress.

“This is a campaign about ideas,” Gunnels says. “When senator Sanders is fighting for his economic agenda, those proposals are going to have to be turned into legislation, there will be committee hearings, senator Sanders using the bully pulpit, and we can have a big strong debate on all of those issues.”

“It’s what senator Sanders has said throughout this whole thing,” Gunnels says. “He can’t do it alone.”