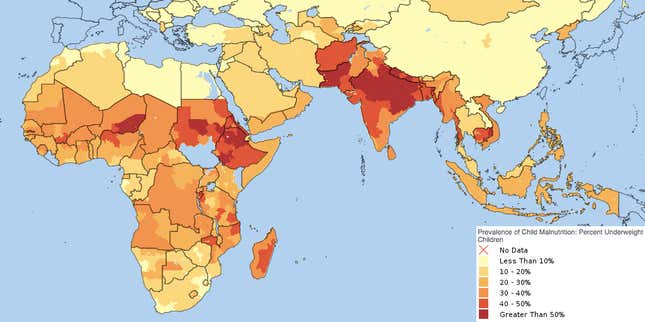

Some 170 million children globally suffer from a condition that we have no easy treatment for. However, new studies suggest that the answer may lie in a radical treatment: fecal pills (or, more plainly put, poop pills).

The condition that needs treatment is malnutrition, and it is mainly the result of extreme poverty. Malnourished children lead stunted lives. Their height, intelligence, and overall well-being is far below well-nourished children of similar age. It is not fair for any child to not be able to live to their full potential, but the problem is widespread—more than 40% of India’s children are stunted.

Yet, ironically, the solution to the problem is not simply to provide more nutrition. Recent studies have shown that chronic malnutrition changes the population of beneficial bacteria in the gut, which makes it harder for these children to absorb key nutrients even when they are fed good food.

To understand why this might be the case, researchers from the US and Malawi took samples of gut bacteria from malnourished children in Malawi. They then placed those microbes in the sterilised guts of mice. The results of the study, published in Science, show that those mice, despite being fed nutritious food, suffered from stunted growth, including abnormalities in muscles, bones, liver and the brain. This suggests that poor gut bacteria are a cause of malnutrition.

In a separate study, researchers at the University of Lyon in France wanted to find which bacteria could help fix the problem. So they fed two groups of mice—one of which had no bacteria in the gut and the other had bacteria normally present in mice guts—with the same nutritious diet. Their results, published in a separate study in Science, show that a strain of bacteria—Lactobacillus plantarum—was helping produce growth hormones that helped mice with gut bacteria live healthier lives. Those without any gut bacteria had stunted lives. Other strains, such as Ruminococcus gnavus and Clostridium symbiosum, may have similar impact.

Though scientists will still need to replicate the results in humans, the experiments provide hope for a long-sought treatment to a disabling condition. And, yet, even if these results can be replicated in humans, developing large-scale bacterial transplants isn’t going to be easy.

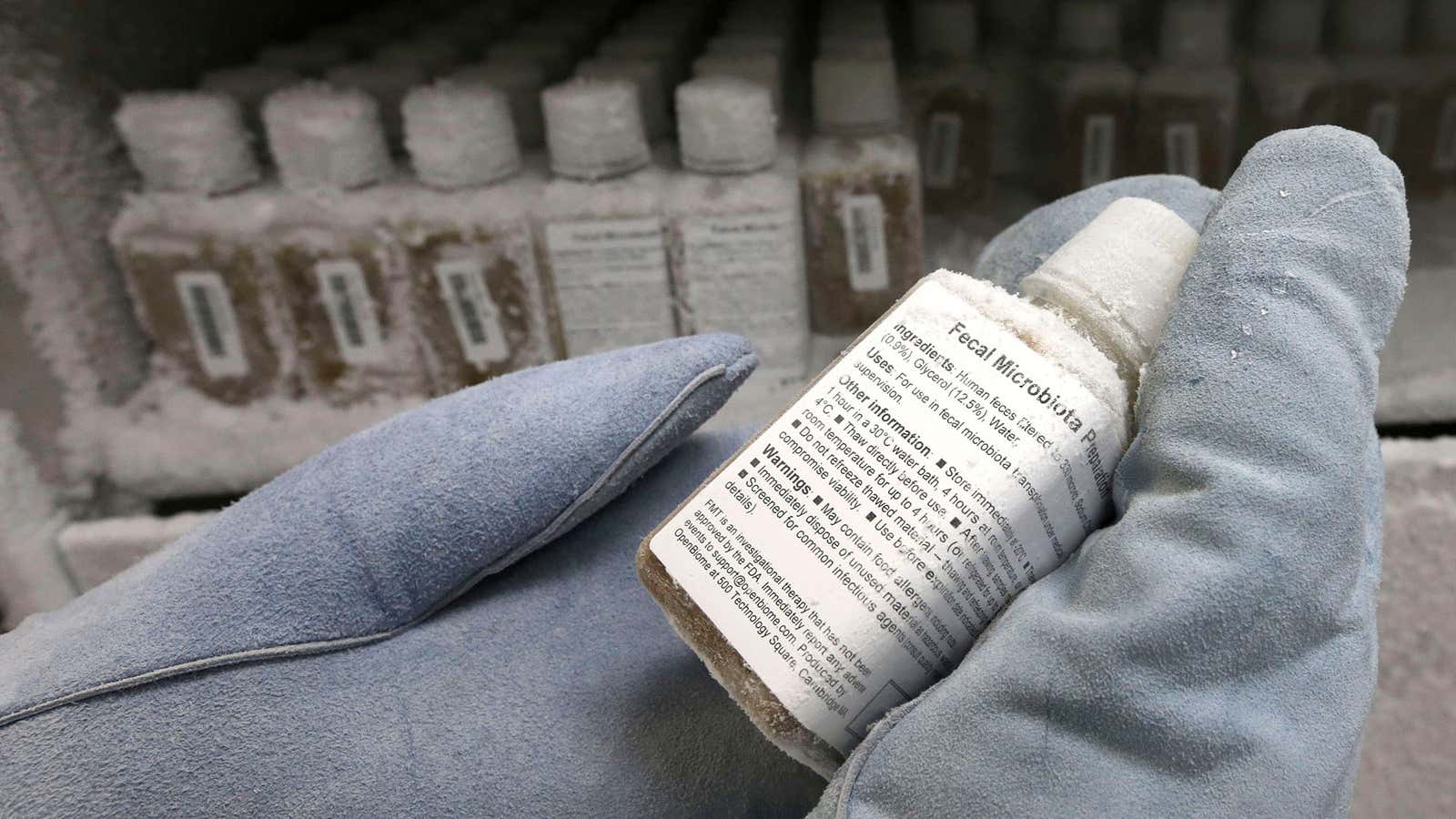

Most microbes found in the wild are notoriously difficult to grow in the lab. So scientists have found an innovative workaround: fecal transplants. The idea is to collect good bacteria living in the guts from the feces of healthy individuals. Then, after necessary treatment, they can be transplanted in the guts of unhealthy individuals.

Though this might sound disgusting, fecal transplants are already showing success where other attempts have failed, such as in treating Clostridium difficile infection—a bacterial disease which has no effective treatment and kills thousands of people globally. But there are practical difficulties for both the donor, who provides fresh feces, and the recipient who has it implanted in his or her own gut.

So another workaround has been to create freeze-dried fecal pills. This lets doctors store feces from healthy donors for longer and lets patients consume them as they would any other capsule. There are many undergoing clinical trials that use fecal pills to treat a range of conditions—from simple infections to obesity. With more research, it could soon become a promising way to treat malnutrition too.