It’s been a terribly rough ride for the Republic of Ireland in recent years. So we hope the island nation takes a measure of pride in the fact that it was able to sell €5 billion ($6.5 billion) worth of 10-year government debt to investors today.

Unfortunately—and it pains us to say it—that pride is misplaced. Ireland’s ability to return to the bond markets says next to nothing about its fiscal position, its banking system or its prospects for growth. Rather it has to do with the somewhat special role Ireland has been given in the European debt drama, that of the “model debtor.”

Perhaps we’re being a bit unfair. If nothing else, the Irish government has enforced the austerity prescribed by the trio of European powers known as the “troika” as part of the bailout package it received in 2010. The government has introduced spending cuts and tax increases worth about 12% of GDP since the collapse in 2008, according to Bloomberg. (The New York Times puts it at 18%.)

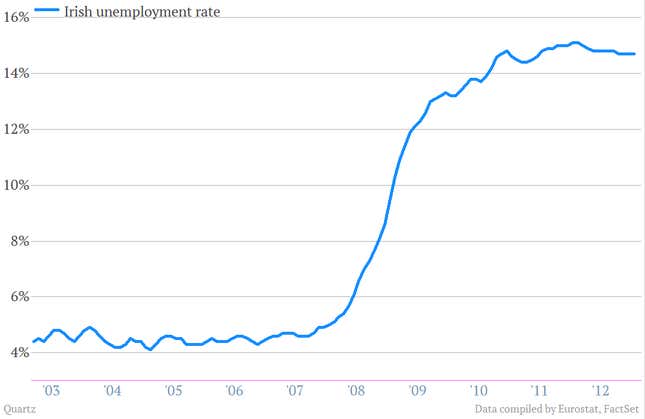

But those cuts have been incredibly painful. By virtually any metric, Ireland’s economy is in terrible shape with few signs of significant improvement. Just look at the unemployment rate, for instance.

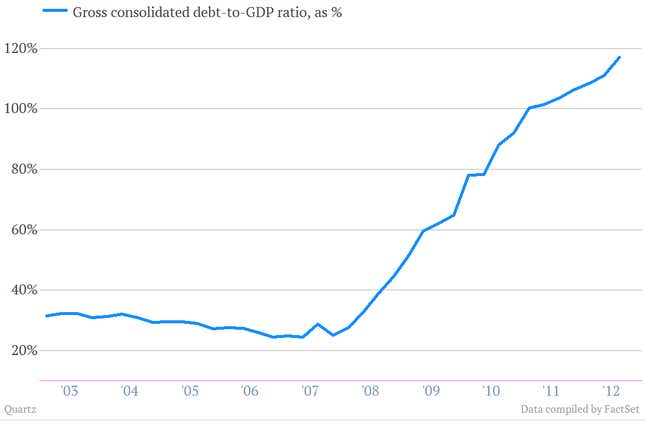

Nor has the austerity push in Ireland showed any sign of cutting the country’s debt load. In fact, through September, the government’s debt-to-GDP ratio jumped 5.9% percentage points, to 117%. That was the fastest rise in debt burden of any of the euro zone countries. Credit rating firm Moody’s forecasts that the ratio will hit 120% by the end of 2013.

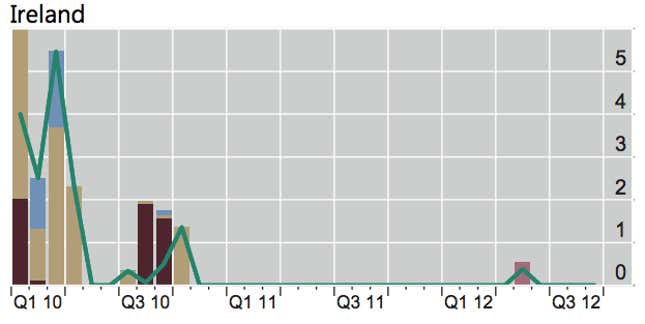

Nor has Ireland’s benighted banking system shown any ability to stand on its own two feet. Banks have hardly been able to borrow money in the markets since 2010. Look at this chart from the Bank of International Settlement, which shows quarterly bank bond issuance. That means the banks are getting the money needed to fund their operations from the Irish central bank and the ECB.

Now, it’s true that Irish GDP has shown some signs of life. It grew 0.2% during the third quarter, the last period for which data was available. But if austerity was supposed to unleash a surge in economic growth, we’re still waiting for it.

Listen, we don’t want to rain on Ireland’s parade. But the only way to read its ability to sell debt today is as a sign that the markets expect the ECB to be there if anything goes wrong, not that they have faith that Ireland fiscal, economic or financial futures are especially bright.

Then again, given the worries about how Italy’s post-electoral political crisis might drag down the euro zone, the fact that there’s still faith in the ECB is, on the whole, a pretty good thing.