Everlane: The San Francisco clothing company that launches t-shirts like they’re iPhones

When the San Francisco-based apparel brand Everlane launched in 2011 with its simply designed t-shirts, ties, and bags in luxe materials, it could easily have been yet another e-commerce site seeking to “disrupt” the crowded market for high-end basic clothing.

When the San Francisco-based apparel brand Everlane launched in 2011 with its simply designed t-shirts, ties, and bags in luxe materials, it could easily have been yet another e-commerce site seeking to “disrupt” the crowded market for high-end basic clothing.

Five years later, Everlane is one of the most interesting, innovative companies in the industry, and reportedly seeking a valuation upwards of $250 million. Even if you haven’t heard of Everlane, you’ve probably seen it—on that chic, no-nonsense young woman in your office who always looks smart, but never like she’s trying too hard. Everlane might make her crisp button-down shirt, swingy cropped trench coat, or shiny loafers. (Everlane makes menswear too, but womenswear makes up the majority of the business.)

In Everlane’s Mission district headquarters—a sky-lit industrial space that appears to have an Instagram filter pre-applied—young women swathed in black ribbed sweaters, scarves, and leather jackets breezed past a display of the brand’s latest sleek leather backpacks and waffle-knit sweater dresses. On an L-shaped couch, founder and CEO Michael Preysman sat down to talk about how they’ve done it so far.

From the get-go, Everlane employed the Warby Parker-proven strategy of selling classic styles directly to customers online, at prices lower than the competitors. The company touted “radical transparency” as its mission, and told customers the exact cost breakdown of their clothing—accounting for materials, labor, duties, and transport. It also showed them beautifully produced photos and videos of the factories worldwide where it was made.

None of this would have mattered, of course, if people didn’t like the clothes—but they did. With a strategy that has more in common with Everlane’s Silicon Valley neighbors than it does with its fellow fashion companies, Everlane has built a collection of go-to garments that actually work for real life. There’s no disappointing cardigan or jacket you can’t get your arm into; these are the pieces you pack in your carry-on.

“We don’t want fashion”

The flat-front pants, pocket tees, and round-neck cashmere sweaters that Everlane sells might look basic, but behind them is a total reinvention of what it means to be a fashion company. Being on-trend is not the goal, Preysman said.

“We don’t want fashion,” he said. “We want lasting styles.”

Since Everlane launched with a single t-shirt in 2011, the collection has grown to include jackets, sweaters, pants, button-downs, silk dresses and blouses, sweats, and leather bags and shoes, which it has shipped to over 350,000 customers. And it still sells that basic t-shirt.

Everlane doesn’t disclose revenue today, but the company reported sales of $12 million in 2013, and double that in 2014. Privco, a firm that researches private companies, estimated Everlane’s sales at $35 million for 2015. While US retailers such as Banana Republic and J.Crew flounder to recapture the market for everyday basics, for a certain upscale, urban shopper Everlane has stepped in, and, well, filled the gap.

Its model allows Everlane to avoid one of the biggest inefficiencies of retail fashion: Traditionally, companies create collections around seasons, so designers currently working on spring 2017, for example, might be sketching out t-shirts, shorts, dresses, and outerwear that will hit stores a year from now. Once those clothes have been manufactured, they’ll sit there for a few months until unsold pieces are discounted to make room for the next delivery—a business model so inefficient that the Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA) recently contracted with the Boston Consulting Group to try to fix it.

Everlane, on the other hand, has judiciously added other product groups to that basic t-shirt—cashmere sweaters, leather shoes, wool trousers, and so on—that reflect how customers actually shop and layer their clothes. Most of us don’t go looking for our spring 2017 wardrobe; we search out a new sweater, silk blouse, or a fresh jacket. Everlane sells all of those year-round.

Don’t separate designers from decision-makers

When it comes to organizational structure, design, and development, Everlane doesn’t look to its competitors in US retail, such as Gap or J.Crew. Instead, Everlane has emulated Pixar and Google.

At Gap, for example, designers create the collection, and then pass it on to merchandisers. Merchandisers then decide what products should ultimately make the cut, based on sales data and business goals, among other factors.

“I find that dysfunctional,” says Preysman. “Your designer should understand your customer. Your designer doesn’t understand your customer, then that’s the problem. Don’t try to solve it by building a merchandising team that is going to stand for the customer. The right organization should be able to do it for both. I think Pixar does this really well.”

At Pixar, it’s the filmmakers, not the studio executives, who control movies’ creative direction: “Creative power in a film has to reside with the film’s creative leadership,” wrote Pixar co-founder and president Ed Catmull in the Harvard Business Review. “As obvious as this might seem, it’s not true of many companies in the movie industry and, I suspect, a lot of others.”

Indeed, Gap has been criticized for thwarting creative talent—including that of former creative director Rebekka Bay—with its risk-averse strategy that divides creative talent from the key decision-makers. Today, Bay is Everlane’s head of product, a department that merges design with customer feedback and research.

Product release is only the beginning

“What we do is we try to create out of our own inspiration,” Preysman said. “And then listen to customers to edit.”

Much like Apple and Google, Everlane treats design as an iterative process; a product’s release is just one stage in its ongoing development.

“You make something. You see if you like it… You talk to people. You adjust,” said Preysman. ”It’s always like: release, edit, release, edit, release, edit.”

Kelli Dugan, Everlane’s head of product strategy, pulled a pair of black women’s pants off a rolling rack by way of example: the latest iteration of a slim trouser first introduced last year. Based on customer feedback, Everlane had improved the trousers by adding belt loops and menswear-style details such as interior closures and interfacing.

“We were trying to have a cleaner aesthetic, which is actually silly, because not everybody’s hips and waist are the same size,” said Dugan. “We’re getting better.”

As it happens, I had actually provided a bit of the customer feedback on those trousers. I had bought and returned them a few months prior, because I found the fabric thin and itchy—a comment I included when a form requested my reason for return. The new version that Dugan was holding was made of a softer tropical wool.

“We were getting feedback on the fabric being itchy,” said Dugan. “That’s why we really spent time developing this new fabric.”

Don’t talk about a product’s features—talk about how people will use it

To design functional clothes that fill a need, Everlane always starts with questions about the customer: ”How is she going to wear it? Where is she going to take it? And then what product do we design for that?” said Preysman. “Everything is always about end-use for us.”

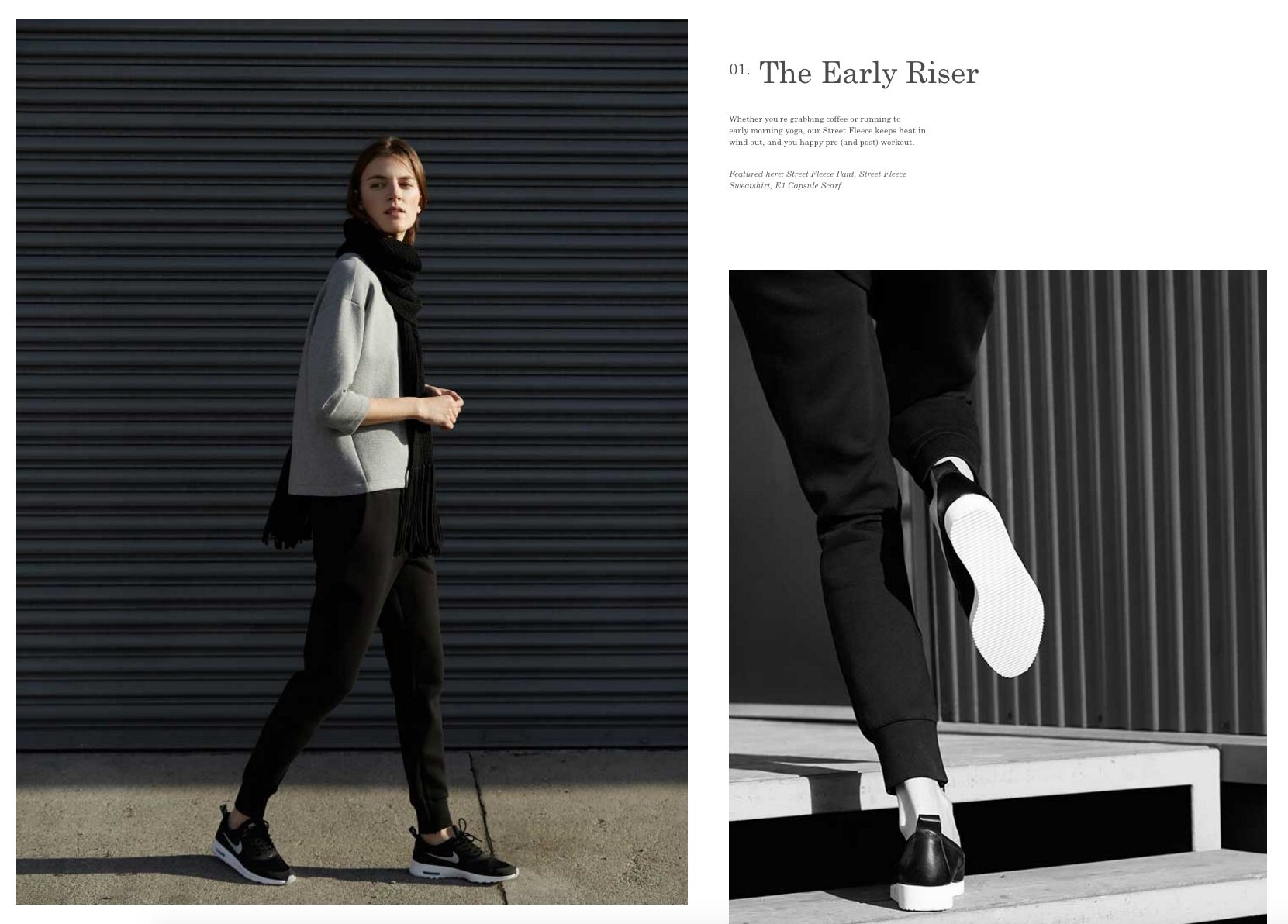

For example, a recent collection of “street fleece”—Everlane’s answer to athleisure—was designed for wearing on the weekend:

“You roll out of bed on a Saturday, and either you’re going to work out or maybe you’re going to meet a bunch of friends,” said Preysman. “You don’t want to spend too much time trying to do makeup and all this stuff, but you also want to look put together, and have it be somewhat comfortable and flexible.”

Much like Apple executives launching a new product discuss how customers can use a new smartwatch or iPhone, rather describing the technology behind it, Everlane’s creative team made the street fleece campaign all about the “end-use,” making the case that the collection was equally appropriate for a day at the museum and Netflix on the couch.

The message is the medium

Everlane doesn’t have retail stores, and Preysman doubts it ever will, in the traditional sense.

“I don’t know of any retailer in the apparel world that I think has a great experience,” said Preysman, adding that Apple and Ikea create the sort of immersive experience he would want for customers.

Instead, Everlane uses beautifully shot videos and photographs to craft an experience online—as well as on social channels such as Instagram and Snapchat—and it hosts parties and pop-up shops to interact with customers in real life.

“It’s just all about how you use the medium that you have.”

Instead of showing new styles in traditional ad campaigns or expensive fashion shows, Everlane shares images on its website and social channels with anticipation-building release dates, and the opportunity to sign up for a waiting list.

Coming this spring: those tropical wool trousers, buttery tan leather backpacks and boots, and—of course—new-and-improved t-shirts.