Economist Robert Gordon has spent his career studying what makes the US labor force one of the world’s most productive.

And he has some bad news.

American workers still produce some of most economic activity per hour of any economy in the world. But the near-miraculous productivity growth that essentially transformed the US into one of the world’s most affluent societies is permanently in the country’s rearview mirror.

In his magisterial new book, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, the Northwestern University professor lays out the case that the productivity miracle underlying the American way of life was largely a one-time deal. It was driven by a flurry of technologies—electric lights, telephones, automobiles, indoor plumbing—that fundamentally transformed millions of American lives within a matter of decades.

By comparison, Gordon argues, today’s technological advancements—Uber, Facebook, Amazon.com—will touch the productivity of the American economy lightly—if at all. And a combination of demographic factors, such as the aging of the US population, and sociological problems such as growing inequality and educational performance that’s worsened in comparison to many other rich nations, will stymie economic growth for the foreseeable future.

Gordon visited Quartz’s New York offices recently to talk about his book. In a wide-ranging discussion, he laid out why the airline industry is a microcosm of American economic history, why Moore’s Law isn’t a law and why he’s “at war with the techno-optimists.” Here’s an edited excerpt of our conversation.

Quartz: I can’t think of a better day for you to have come in. We just got the productivity numbers for 2015, and they weren’t good. Productivity growth declined to 0.7%, from 0.8% the year before. And, spoiler alert, this is kind of what the heart of what your book says. Right?

Robert Gordon: That’s even worse than my book forecast. My book forecast, going out 25 years in the future, productivity growth of 1.2%, which is not that different than in the 40 years since 1970. We had a brief respite from slow productivity growth in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the so-called “dot-com” era when we had massive investment to convert offices to use the internet [and] the beginning of e-commerce.

But if you leave aside that decade from 1995-2005, labor productivity growth in the US has only been 1.4% since 1970. And I’m predicting a slight slowdown in that.

The actual numbers for the last six years have come up just about half what I’ve been forecasting. So, we’ve got something really very big going on.

So in a high labor productivity economy, you get a ton of economic growth with relative fewer labor hours worked. Is that right?

By definition, output can grow higher, either with more hours worked—that is more employees, or each employee working more hours—or we could have higher output per hour. And either is source of output [GDP] growth.

But only output-per-hour makes us better off and creates the extra income, that allows workers to be paid more for each hour. So one of the reasons that wages have been stagnating is that productivity growth—output-per-hour—has been growing so slowly.

One of the things you talk about is this golden age when there was a surge in productivity growth, from roughly the 1920s to 1970s.

That’s right.

While the inventions came in the late 19th century, it took a lot of time to figure out how to use them productively. It took time for the price of electricity to come down. It took time to invent all the new kinds of engines and portable tools, that used electricity and replaced the bulkiness of the old steam powered factories.

It took time to figure out how to take an internal combustion engine and get the power from the engine to the wheels through transmission differentials, all the things that are essential parts of motor cars.

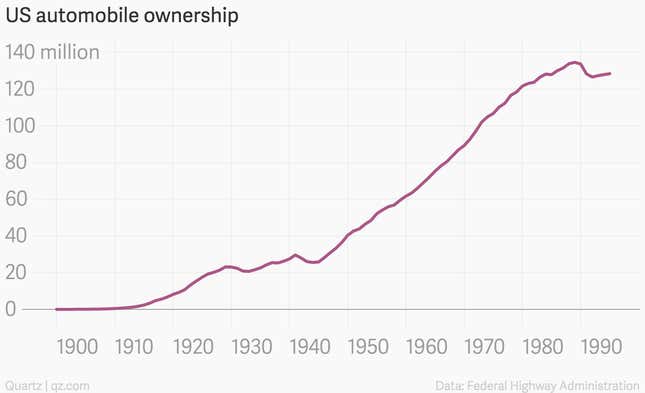

So it took a good 20 years for the first cars to come out, and trucks. And then another 30 years for them to make their way through the economy. Starting with virtually nothing in 1900, by 1930 we had 26 million motor vehicles, almost one per household.

This period of booming labor productivity growth, from the 1920s to the 1970s, was also an era of rising wages, and after the Great Depression, rising unionization and levels of employment.

So in other words, employment was booming and the economy was booming. It wasn’t as if we had growth on the back of a smaller and smaller labor input.

That’s right. Remember of course, we had a big slump in employment during the 1930s. But productivity began to grow rapidly in the late 1930s. We had an investment boom in the last part of the 1930s. There was little private investment during World War II, but a huge amount of investment financed by the government.

In the book, you note that the number of machine tools in the country doubled between 1940 and 1945—and it was all paid for by the government.

It was all paid for by the government. And people wonder how we had such high productivity coming out of World War II. We completely reinvented our whole machinery of production. And virtually installed a new capital stock for the United States during World War II.

Let’s talk about this notion of the startup culture, the disruptors, and the potential they have for changing the productivity potential of the US economy. What does Uber do for productivity growth?

If the software allows [drivers] to take up driving jobs with less downtime, it should make them more productive than traditional taxi drivers because the access has improved. So, if the drivers have less downtime in between their Uber jobs, if the minute they let an Uber fare off…

…They know where their next fare is and they don’t have to circle blocks waiting for a customer.

Gordon: Of course, for decades you’ve been able to order taxis on the phone or [online] so it’s not that ordering taxis is something new. But the Uber phenomenon makes it more transparent and easier to use. So it should raise productivity for those who are continually driving.

It may also reduce productivity in the short run, because you might have more idle [non-Uber] taxi drivers waiting for fares.

Meaning, for yellow cab drivers, if some of their fares are increasingly taking Uber, they’re going to spend more time circling around Manhattan. But this won’t have a large impact on the economy will it?

No. And Airbnb is probably not going to show up in the statistics at all. If people are renting out their private residences and apartments, I can’t even see that getting into the statistics.

Here’s a dumb question. Isn’t low productivity, in some sense, good for workers, in that it implies that the economy is employing a lot of people, working a lot of hours. Wouldn’t that be a good thing?

Oh sure. We want to have more hours and we want to have more output per hour.

It takes more productivity to get wages to go up. Because, otherwise, how could firms afford to pay higher wages, unless the workers are producing more?

Now of course in the normal course of events, that higher productivity is, in part, dependent on firms buying plants and equipment and equipping the workers with better tools to achieve that higher productivity growth. But eventually, if there are no new ideas or new innovations, there’s no need for new machines, because they do the same thing as the old machines.

One of the most fascinating parts of the book, is where you talk about Moore’s Law. I was really glad to see that you basically say, “It’s not a law. It’s a conjecture. It’s a forecast.”

It’s a forecast and it’s remarkable how long it’s been accurate. Hal Varian, the chief economist at Google, confirmed my conclusion that I reached from the data…that shows Moore’s law petering out.

And he said, “You know, it’s because computers really are fast enough to do most of what you need to do.” In this office [gestures to the Quartz newsroom] nobody is slowed down because their computers aren’t fast enough anymore.

When personal computers first came out, we were using floppy disks, it took forever to scan from the beginning of a document to the last page, if you wanted to change something in the conclusion.

All that is over now, our computers are as capable as we need. The technological drive is shifting. We’re now being held back by the limitations of batteries, and so there’s enormous technological innovation and investment in batteries now. And we don’t need it as much in computers.

One chunk of your book that will resonate with people is this section about airlines, which are like a microcosm of the nation’s productivity history.

That’s right. And the point of the section on airlines, is how far we got just in about eight years from the 1930s: From nothing, to a viable air transportation system. And I think one of the most surprising things … is that you could go from New York to Chicago, just about as fast in 1937 as you can today. You spent more time in the air but you spent less time on the ground, getting through the airports.

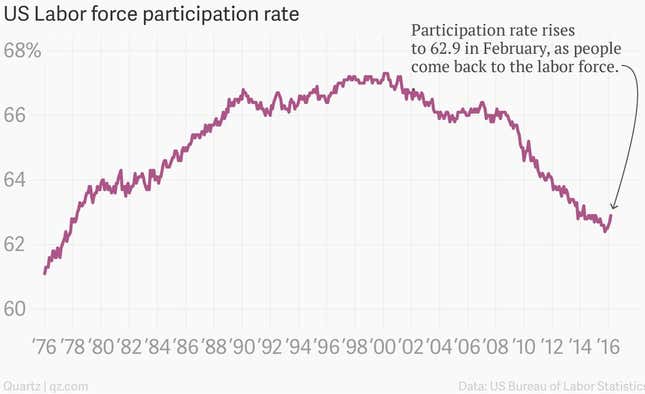

Your forecasts for growth are not good. You talk about not only the decline in labor force participation due to the baby boomers, but also various social and demographic factors. There’s another group of people who you refer to as the techno-optimists who see things very differently.

Let’s make a distinction here. There’s the whole issue of innovation and technical change. There I’m at war with the techno-optimists. They think we’re on the verge of some great acceleration of productivity. I think we’re going to see much the same kind of productivity numbers that we’ve seen over the last 40 years.

But then I start talking about headwinds: Inequality, retiring baby boomers, plateauing educational attainment and the need to come to grips with growing debt due to Medicare and Social Security running out of money. And there, the techno-optimists have nothing to say.