Veteran Chinese journalist and historian Yang Jisheng investigated the massive death toll from China’s Great Famine, and the government policies that caused it, in Tombstone, a book that is often considered the most authoritative account of the man-made disaster that stretched from 1958 to 1962.

Published in 2008, the book is still banned in Mainland China. Recently, Yang himself was banned from traveling to the US to accept an award for “consciousness and integrity in journalism” due to be presented today (March 10) at Harvard University.

In Tombstone, Yang detailed how over 36 million Chinese people died over those five years, as a direct result of Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong’s “Great Leap Forward” and other policies. The Communist Party’s official explanation of the famine lays much of the blame on unusual weather and fraying relations with the Soviet Union, although Mao also publicly took blame afterward. Yang spent years searching provincial and local archives and to uncover new information on the death toll, incidents of cannibalism, and the Party’s systematic efforts to cover up the disaster.

Yang, 75, a retired correspondent from China’s official Xinhua news agency, lived through the famine years himself. His father died of starvation in 1959, but as a young man he never doubted the Party’s policies, he wrote in the book’s prelude, because of his ignorance and “the powerful political pressure over the whole society.”

The book was first published in Chinese in Hong Kong, and went into eight reprints, before being published in English in 2012.

Xinhua has forbidden its former employee from traveling to the US to collect his prize, Yang said last month, and state-backed media are downplaying the award. “Western awards fell like rain on Chinese ‘dissidents’ in recent years,” nationalistic state tabloid Global Times wrote (link in Chinese) after Yang’s travel ban was reported by Western media. “We should be more wary of it,” the editorial said. A speech by Yang will be read at the awards ceremony today, organizers told Quartz.

Quartz has taken some of Yang’s meticulous research explaining the root causes of the famine, and its widespread effects, and put it in chart form, in order to illustrate the size of the tragedy.

Natural disaster or man made?

The Communist Party’s official account of the Great Famine says that government policies were at fault, but it also blames nature. According to official figures, areas in China affected by drought or flood reached 28 million hectares—more than the total area of France—in 1961. The previous year also recorded the lowest grain output in more than a decade.

But those figures are fiction, according to Yang’s reporting. He uncovered a document written by Xue Muqiao, former head of the national statistics bureau, in 1958 that said “we give whatever figures the upper-level wants,” to overstate disasters and relieve official responsibility for deaths due to starvation, Yang wrote.

These unreliable data points don’t even correlate with each other, Yang noted. The reported areas affected by drought and flood in 1961 are 15% bigger the previous year, but grain output in 1961 is nearly 3% higher than in 1960.

Yang also investigated other sources, including a non-government archive of meteorological data from 350 weather stations across the country. It showed China’s weather from 1958 to 1961 was normal—there were no big areas of drought, flood, or low temperatures.

Blaming Big Brother

The Communist Party also blames the Soviet Union for dealing a huge blow to the economy. After Mao sparked the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis by bombarding the Kinmen Island in 1958, Communist China broke with the Soviet Union, the Big Brother of the socialist camp. Starting in June of 1959, the Soviet Union breached its promise to support China’s nuclear program, and later scrapped over 600 contracts with China on science and technology. But that happened after the famine started, and has nothing to do with agriculture, Yang wrote.

China also began to pay back debts to the Soviet Union early—not because the creditor asked, but because Mao wanted to show that Chinese Communists don’t rely on others, Yang wrote. At the same time as people at home were starving, China increased its aid to socialist countries including North Korea and Albania, Yang reported:

Mao’s “Three Red Banners”

The long history of China’s obsession with numbered policies starts with Mao.

The Three Red Banners—the “General Line for socialist construction,” the “Great Leap Forward” and the “people’s communes”—laid out how Mao’s socialist policies would transform China. But they are the defacto culprits of the Great Famine, Yang said.

The first banner is an ideological slogan that calls on Chinese people to build a socialist state. The Great Leap Forward, initiated by Mao in 1958, aims to transfer China into an industrialized country. And the people’s communes put households together in rural areas where they shared everything from food to farm tools—a way to discount individuality and centralize more manpower and resources for agricultural and industrial production.

In 1957, Mao declared that China’s steel production must surpass that of the UK within 15 years, echoing the Soviet Union’s plan of surpassing the US in 15 years. More immediately, he said 1958 steel production should be two times what it was the year before.

One man’s demand became a campaign for 90 million Chinese people. Any steel objects, from nails to pots to temple bells were melted down when there was not enough iron ore, Yang wrote. Production went way up:

But millions of homemade steel furnaces only produced useless pig iron, Yang noted, which wasn’t strong enough for construction and manufacturing.

In order to meet Mao’s radical industrial expansion goals, China traded agricultural products for machinery, while hundreds of millions of peasants were starving, Yang wrote. Agricultural products accounted for 76% of China’s exports in 1959, the highest in over a decade. Machinery as a share of China’s imports plummeted in 1961 as China ended the steel-making craze.

The agricultural sector ran on the same logic as industrial development: Mao laid down unrealistic demands, his subordinates followed them to extremes, and nationwide, “arbitrary orders messed up the economy,” Yang concluded. Official data released by the national statistic bureau in 1984 shows grain production in 1958 was 400 billion jins ( 200 million metric tons), but at the time that number was exaggerated to 850 billion jins, Yang wrote.

The exaggeration came because local level Communist Party officials tried to meet their superiors’ expectations—even if it meant telling lies. Mao first noted in a 1958 meeting that the Party should promote examples of bumper harvests, Yang wrote, supported by propaganda from the Party’s official mouthpiece People’s Daily’s newspaper. On Aug. 13 of 1958, the paper profiled a Hubei commune that produces 36,900 jins (around 19 metric tons) of rices per hectare, Yang reported. That’s nearly triple production rates with modern farming methods—China produced 6.7 metric tons of rice per hectare in 2012.

These exaggerations were ultimately deadly for farmers and workers. Under a state compulsory purchase policy initiated at the end of 1953, all farmers had to sell their grain to the government, and then the government supplied the grains back to the people. Because local officials had overstated what farmers could produce, they were compelled to find that much to sell to the government, and take any grain storage local peasants had for themselves.

So, for example, in 1959, even though the annual grain yield dropped 15% from the year before, state purchases jumped nearly 8%, figures complied by Yang show.

“Whoever is hiding a single grain, he is hiding a bullet; whoever is hiding a single grain, he is a counter-revolutionary,” a commune in northeastern Liaoning province chanted as it carried out state purchase duties, Yang reported, citing a local archive. The commune’s Party chief even threatened to hang his subordinates if they couldn’t meet the target, Yang wrote.

Nonetheless, China’s agricultural production fell during the first years of the Great Leap Forward.

How many people actually died?

In 1961, China’s food ministry and national statistics bureau tallied up China’s population loss in the famine years, in a secret document given only to Mao and then-premier Zhou Enlai. The document was destroyed after Zhou read it, Zhou Boping, deputy food minister, told Yang in 2003, and the numbers in it were never revealed. Still, the official public data show a spike in deaths:

In addition to starvation deaths, there were several thousand cases of cannibalism nationwide, Mao’s secretary Li Rui told Yang in 2004. “Survival overrides anything; animal nature overrides humanity,” Yang said. After a mother from a village in North China’s Gansu Province cooked and ate her younger daughter, Yang reported, citing local archives and reports, her elder daughter begged her: “Mom, don’t eat me, I’ll help you build fires when I grow up.”

Many more died at the hands of Communist Party officials. In Mao’s hometown Hunan province, for example, more than 2,000 people in two counties were beaten to death from 1959 to 1960—peasants who didn’t or couldn’t turn in the right amount of grain storage or questioned Mao’s policies were tortured and killed, Yang wrote.

In 1983, the Chinese government for the first time published the country’s population size in the 1950s and 1960s. Yang calculated China’s normal mortality rate at 1.047%, and abnormal moralities, of 16.2 million between 1958 and 1961. Using the same methodology, he calculated the population that failed to be born during the same period at 31.5 million. Overall, China had 47 million fewer people because of the Great Famine, according to China’s own official data.

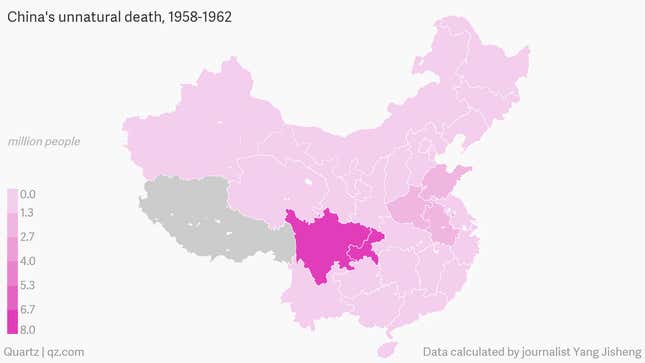

Yang also broke down the death toll in different regions, referring to an official archive of population by provinces. Central Sichuan province (which included Chongqing city at that time) registered the highest death toll at nearly 8 million. The 20 million total deaths, when calculated by provincial statistics, is higher than the one calculated by state figures, showing discrepancies in data collecting. (China’s western Tibetan region is not included in the official archive.)

Provinces headed by officials who followed Mao’s directives closely had greater famines, Yang notes. That explains why minority ethnic groups’ autonomous regions—including Tibet and Xinjiang Uyghur region—recorded smaller death rates. Regions with higher state compulsory purchases of grain but lower re-sales to the public had higher deaths, Yang wrote. Those include Anhui, Shandong, Henan, and Sichuan.

But local party officials often under-recorded death numbers. Academicians looking at the official birth and death rates estimate between 24 million and 44 million people died, Yang wrote. Wang Weizhi, a statistics expert and former police officer who Yang considers most credible, estimated the death toll at between 33 million and 35 million. Yang concluded there were 36 million deaths due to starvation, while 40 million other people were born, who would have been in normal times.

Ultimately, China’s Great Famine that stretched from 1958 to 1962 was one of the deadliest man-made disasters in history:

Mao Zedong, last emperor of China

“Long live the People’s Republic of China, long live the Communist Party of China!” The slogan was first drafted by China’s propaganda department in celebration of Labor Day in 1950. But Mao revised the slogan by ending it with “Long live Chairman Mao,” Yang wrote, citing a former high-ranking Party official.

Then Chinese people chanted it for decades, just as their ancestors had cheered the feudal emperors before Mao.

Mao saw himself as the representative of the whole society and did what Chinese emperors may have dreamed of, but couldn’t—state power permeated into every inch people’s daily life through modern weapons, transportation, and communication tools. The last emperor of China was Mao, Yang wrote.

But eventually, it is the system—the Communist authoritarian regime—that gets the credit. The Party monopolizes all economic resources, controls people’s thoughts, guards its regime with a grand army, and runs the state in the disguise of democracy, Yang concluded.

At the end of the book, drawing a lesson from the Great Famine, Yang calls for the establishment of a “constitutional democracy” and a “mature market economy.”

“If a regime takes the protection of the ruling group’s interests as its top priority, it can never be convincing to the public; then it lacks legitimacy,” Yang wrote. Constitutional democracy, along with other “false ideological trends,” has been banned in China since 2013.