E-cigarettes have a problem: They keep blowing up

Shenzhen, China

Shenzhen, China

Last year, self-balancing hoverboards went from must-have Christmas gift to borderline contraband in a matter of months. After faulty lithium-ion batteries caused dozens of fires, US regulators and e-commerce vendors banned their sale, cratering the industry.

Another fast-growing consumer electronic good appears to be following a similar path. More than 10% of adult Americans now use e-cigarettes, which are billed as a healthier alternative to smoking tobacco or marijuana because they heat, rather than burn, a liquid or plant, creating vapor not smoke. But as “vaping” has grown, there appear to be a growing number of instances of the devices exploding, and sometimes causing gruesome injuries.

Just since February, incidents of an exploding e-cigarette injuring a vaping enthusiast have been reported in Nevada, Maryland, Kentucky, Florida, and North Carolina. E-cigarettes are held close to one’s face or often tucked in a pocket, so these accidents can be incredibly dangerous, and disfiguring. One man lost an eye after his e-cigarette spontaneously combusted.

There are no reliable, up-to-date, industry-wide statistics on accidents caused by e-cigarette explosions. The US Fire Administration reported in 2014 (pdf) that 25 fires were caused by exploding e-cigarette devices between 2009 and 2014, and has not provided any update since then. But anecdotal evidence suggests that safety mishaps have grown with the market’s expansion.

Just as with hoverboard explosions, there is a simple, and a much more complicated reason for these e-cigarette accidents. Technically, the malfunctions are usually with the lithium-ion batteries that power the devices. Shoddily produced ones will explode when in use, or when charged improperly with mismatching equipment.

But the deeper root cause is something plaguing the global consumer electronics industry—Western regulators’ inability to keep up with China’s ultra-efficient, ultra-fragmented manufacturing ecosystem, and China’s government having no enforceable oversight at all.

E-cigarette devices present even more problems for safety regulators than hoverboards. The devices very widely, with customizable parts that can be removed, replaced, or tweaked. Consumers who mismatch these switchable devices might turn otherwise safe e-cigarettes into ticking time-bombs.

A fragmented industry

Vaping is already a massive market. The total market size for e-cigarettes and related products is $3.3 billion in the US alone, according to Wells Fargo. Since 2012 retail sales of the devices have nearly doubled, though in 2015 growth slowed noticeably.

Concerns about health and safety are part of the reason for the slowdown (paywall). Big tobacco companies including Reynolds American are consolidating their e-cigarette units and cutting back their forecasts.

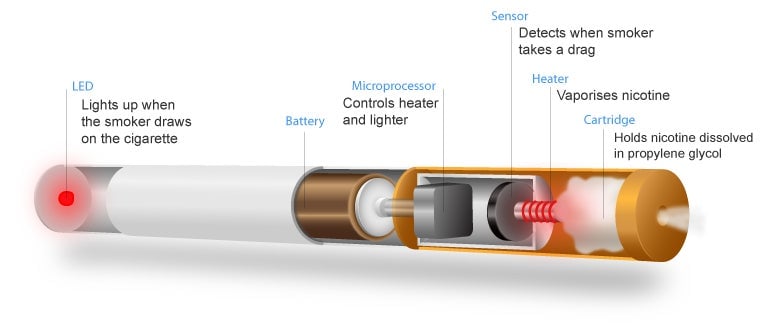

Big Tobacco sells e-cigarette products under names like Vuse and Blu. These products usually resemble paper cigarettes in form but are made with metal, and house a 2-watt rechargeable battery. They sell for about $10 each. Their small batteries mean that the likelihood of an explosion is very low, according to Thomas Kiklas, CFO at the Tobacco Vapor Electronic Cigarette Association (TVECA).

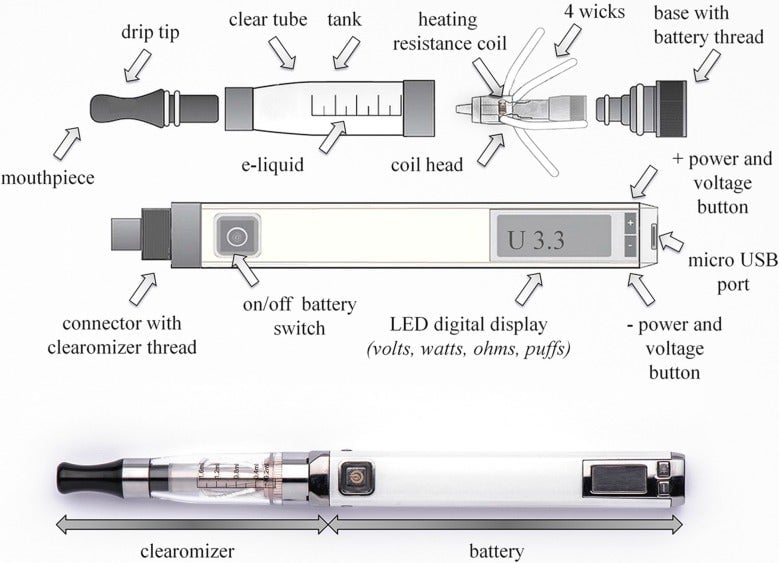

The potentially explosive ones are large devices either shaped like a pen or a tape recorder. These come with batteries sized between 30 and 50 watts, and contain many ways for consumers to customize them—users can tweak the device’s coils, atomizers, and battery to alter the nicotine’s intensity, the vapor’s flavor, or the cloud upon exhale. They can vary in price, selling for $50 for a “starter kit” or up to $600. Typically known as “mods,” they make up a sub-market estimated at $1.9 billion that is growing rapidly.

As much as 90% of the world’s e-cigarettes are made in Shenzhen, China’s electronics manufacturing hub, industry sources tell Quartz. Aspire, Sigilei, Joyetech, and Kanger are some of the largest and most respected Chinese e-cigarette makers. These companies assemble and sell a range of wholesale devices to importers, who go on to market and distribute them under their own brand names.

They rely on component makers in Shenzhen for parts. And a bevy of small Shenzhen factories have jumped into the industry as it’s boomed, making e-cigarettes and e-cigarette parts for importers all over the world. This has led to fragmentation in the market. Derek Kwik, a Hong Kong-based investor who follows the industry, estimates that there are between 50 and 100 e-cigarette manufacturers in China alone, who supply to 100 to 200 brands globally.

When manufacturers face pressure to fill orders and importers don’t bother to check quality, corners get cut, investors tell Quartz.

“Many factories simply can’t or don’t want to supervise the safety standards,” Ronnie Simhi of Faroway Group, an investment fund based in Shenzhen, tells Quartz. “Supervising component vendors requires a lot of money.” In order to ensure that every component used in a final product is safe, e-cigarette makers must have staff regularly check suppliers’ facilities and get updates on their product quality. Component suppliers, meanwhile, might falsify safety certifications, in order to dodge the application fees or close a business deal faster.

Simhi said a “domino effect” is at work in the e-cigarette industry. Retailers demand more competitive prices, and distributors shop around for the cheapest manufacturing costs they can find in Shenzhen.

In consumers’ hands

China’s fragmented manufacturing supply chain offers only a partial explanation for the rise in e-cigarette explosions. Since many e-cigarette devices are so customizable, industry players tell Quartz, consumers must educate themselves about how to use them properly. Certain chargers can’t be used with certain devices, for example, so trade groups and importers typically advise consumers to pair devices with the charger provided.

Other safety precautions are less obvious.

“Some of these electrical safety issues have been caused because people simply don’t understand battery technology,” Katherine Devlin, president of the UK-based Electronic Cigarette Industry Trade Association (ECITA), tells Quartz. “For example, if you have an 18650 battery [a cylindrical-shaped lithium-ion battery with about 3.7 volts] and you pop it in your pocket with some loose change, then there’s a risk of that shorting the battery and causing an accident in your pocket, which is very dangerous.” In larger units, which require higher-watt batteries, “people start stacking batteries, and again, if they don’t understand the electronics of that, that can be very dangerous—it can effectively be a pipe bomb in your hand or in your face.”

“The complicated nature of the devices also increases the likelihood of an accident, and make it difficult to pinpoint an explosion’s cause. After a recent e-cigarette explosion in Canada that left a 16-year-old with fractured teeth and a charred upper lip, e-cigarette users argued about what he may have done wrong. Some commenters allege that the explosion was caused by a shoddy tank made by Aspire. Others claim that the tank itself is safe, but it shouldn’t be attached to a “hybrid mod,” a specific type of e-cigarette design that offers little flexibility in customization. Others noted the user said he blew into the device itself before the explosion, which could have caused the e-cigarette to malfunction.

The retailer that sold the device should be held accountable for not educating the user before he sold it, one vape enthusiast commented. “Irresponsible and lazy sellers are pretty much just as responsible as uninformed/irresponsible users.”

Dangerous fakes

Meanwhile, some Shenzhen factories and vendors are making knock-offs of brand names and copying designs of better-known manufacturers, fooling unsuspecting importers or consumers into purchasing devices they think have been tested for safety. Spotting the fake products can be difficult, and e-cigarette forums are filled with threads where users ask one another if their device is authentic.

ECITA bought a knock-off device online, from a seller claiming to offer a device marketed as the Mutant. The real version of the Mutant was made by Aspire. When the knock-off version was placed in an oven heated to 160 °C (320 °F), the device overheated and the battery propelled out of its casing. Ultimately, ECITA realized that the e-cig’s ventilation hole was too small to properly release gas, which turned the device “into a pipe bomb,” the trade group said.

“The cloning in this sector is appalling and it’s so so dangerous,” says Katherine Devlin, the founder and spokesperson for ECITA. “I don’t think there’s a major problem with the reputable manufacturers themselves and their products, the problem is with the knock-offs. Because they are not going to be to safe, and it’s going to be very difficult for consumers out in the wild to distinguish between a real and a fake.

Western regulators play catch-up

Regulators worldwide have not caught up with growing demand for e-cigarettes.

In the UK, few regulations or certifications cover lithium-ion battery products, including e-cigarettes. According to Devlin, the only requirement for safety is the CE mark, which is a declaration made by the product’s producer, rather than a test. But since it’s difficult to monitor retailer sales of non-CE devices, the certification alone does little to prevent an accident.

In the US, most consumer electronic safety standards are set by UL, a private, for-profit company. Typically, large retailers pledge not to sell electronics that have not been certified by the organization. Barbara Guthrie, a VP of safety at UL, tells Quartz that it has not yet finished developing a certification for e-cigarette devices.

Part of the reason for this is the product’s complexity, she said. Unlike hoverboards, which received a certification in February, e-cigarette devices vary greatly in design and function.

Some e-cigarettes have removable lithium-ion batteries that can be charged independently, for example, while others do not. The US Fire Administration states that e-cigarettes in which the battery is stored permanently at the bottom of a pen-shaped cylindrical device are in danger of propelling while exploding.

US regulators are also wrestling with the regulation of e-cigarettes based on the vapor that they emit and the chemicals put into people’s bodies. Recently the US Department of Transportation forbade passengers from smoking e-cigarette devices on commercial flights, citing concerns about passenger health. Months before that, it issued a temporary ban on storing e-cigarettes in checked baggage or charging them on flights (though passengers can still bring them on board as carry-on items).

Can China step in?

Meanwhile, Chinese authorities have called for greater oversight of the e-cigarette manufacturing industry. Last July, just as Beijing’s ban on smoking began, the municipal government issued a research report on e-cigarettes that concluded that no standards existed to verify a product’s safety and quality.

Some Chinese manufacturers have formed a trade association (link in Chinese) in hopes of creating industry-wide safety standards for factories. It follows several global trade groups that are hoping to influence government policies on e-cigarettes.

But enforcing these standards from within China will be hard. It’s easy for garage entrepreneurs to use Shenzhen’s engineering talents and manpower to produce thousands of sub-standard products, and sell them online to devil-may-care importers. Many sales go through e-commerce sites like Alibaba, Amazon, and eBay, which tend to have lax oversight on product listings.

“New products that are hot mean more Chinese factories will compete for orders. A lot of factories will pop up like mushrooms, and many of them are not qualified or experienced enough to make the products correctly,” says Simhi.

The Chinese government, meanwhile, has a weak track record when it comes to enforcing business policy of any sort. A more realistic hope for Chinese manufacturers would be to find creative ways to guarantee a product’s authenticity to sellers. Aspire, for example, puts scratch-off security codes on their packaging, which verify a device’s authenticity. Sigelei has a similar policy.

“Looking at the Chinese government and Shenzhen on its own, I don’t think there’s anything China can or will do,” says ECITA’s Devlin. “In reality I don’t think this problem will be solved at source.”