The internet is great at enabling images to go viral, but it’s not very good at preserving crucial bits of information about those images—which makes it difficult to prove their provenance.

A New York startup called Mine is developing technology that would let the owner of a digital image claim that ownership by pointing to a time-stamped record on a blockchain. (A blockchain is a public database of transactions where records can’t be easily altered; the bitcoin blockchain, the system underpinning the cryptocurrency, is currently the world’s most popular one. Here’s an explainer we wrote.)

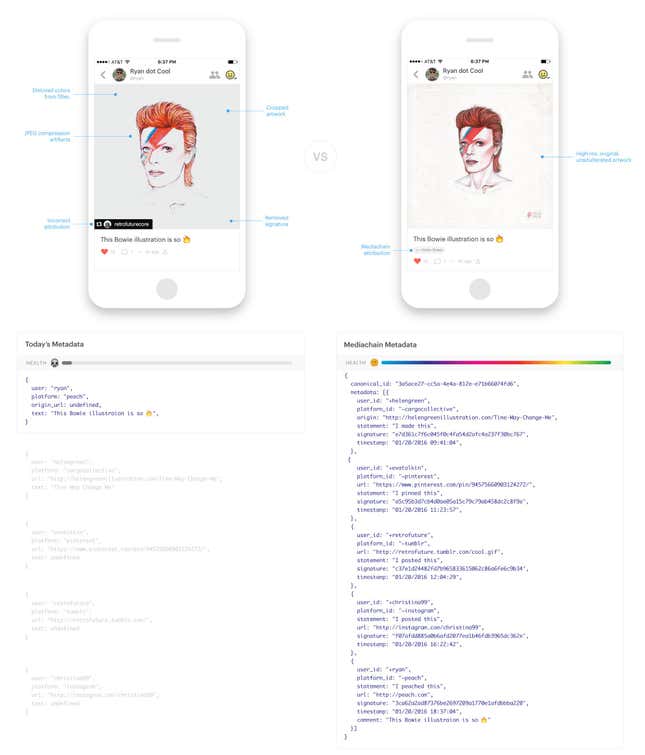

Mine’s system, called Mediachain, would do a few other things, too—for instance, recording alterations made to an image. This means that over time, the history of an image would be captured. This would make it easier to track down an artist for image rights to be licensed, for museums and libraries to share their collections, or for new applications to be built using the data.

If Mediachain existed, the Mine founders argue, then any web user would be able to discover the artist who made this animated David Bowie gif; or the person who photographed The Dress. “If I text you a photo from Tumblr, it’s devoid of all context, attribution, and the entire history of that image is lost. Mediachain hopes to solve that problem with a global shared database of media that can be retrieved using an instance of the media itself,” says Jesse Walden, a co-founder of Mine.

Some of the world’s biggest museums and libraries are similarly eager to solve this problem. For example, the British Library and a number of top universities have formed a consortium to create a common framework to share authorship and other data for the images in their collections.

The difference between Mine’s solution and the consortium approach, called the Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), is that the Mediachain data would be open to everyone, unlocking the ability to easily search for data across many libraries.

Mine is part of a rush by companies big and small who are turning to blockchains as a way to track the provenance of diamonds, food, and even sneakers. Different uses for blockchains also are being tested in the financial sector, where incumbent institutions are furiously experimenting to see if blockchains can strip away many of the back-office costs associated with settling and clearing syndicated loans, powering national stock exchanges, or distributing equity in private companies.

Mine’s plan to make the world’s online images traceable depends on many moving parts. The Mediachain protocol, while designed by Mine, is open-source, so success will depend on how many developers volunteer their time to it. And Mine itself has no clear business plan beyond hoping for Mediachain’s success. “Our goal is to get adoption around the protocol, [then] provide services easy to integrate with Mediachain,” Walden says.

But perhaps the biggest obstacle it faces is resistance from its target users: big institutions with millions of images in their libraries.

As Rob Sanderson, an information architect at Stanford who plays a leading role on IIIF, points out: ”Cultural heritage organizations have a great sense of pride in their collections, and using a system that divorces the representation of the object from its owning institution like Mediachain does … is unlikely to see a groundswell of adoption in the short term.”

Ed Silverton, a developer who works on IIIF, agrees that getting traction won’t be easy for Mine. But he sees potential in its system. ”The next phase, beyond libraries as these central things, is more of a global library that they all contribute their content to,” says Silverton. “Mediachain will give libraries this jumping off point.”