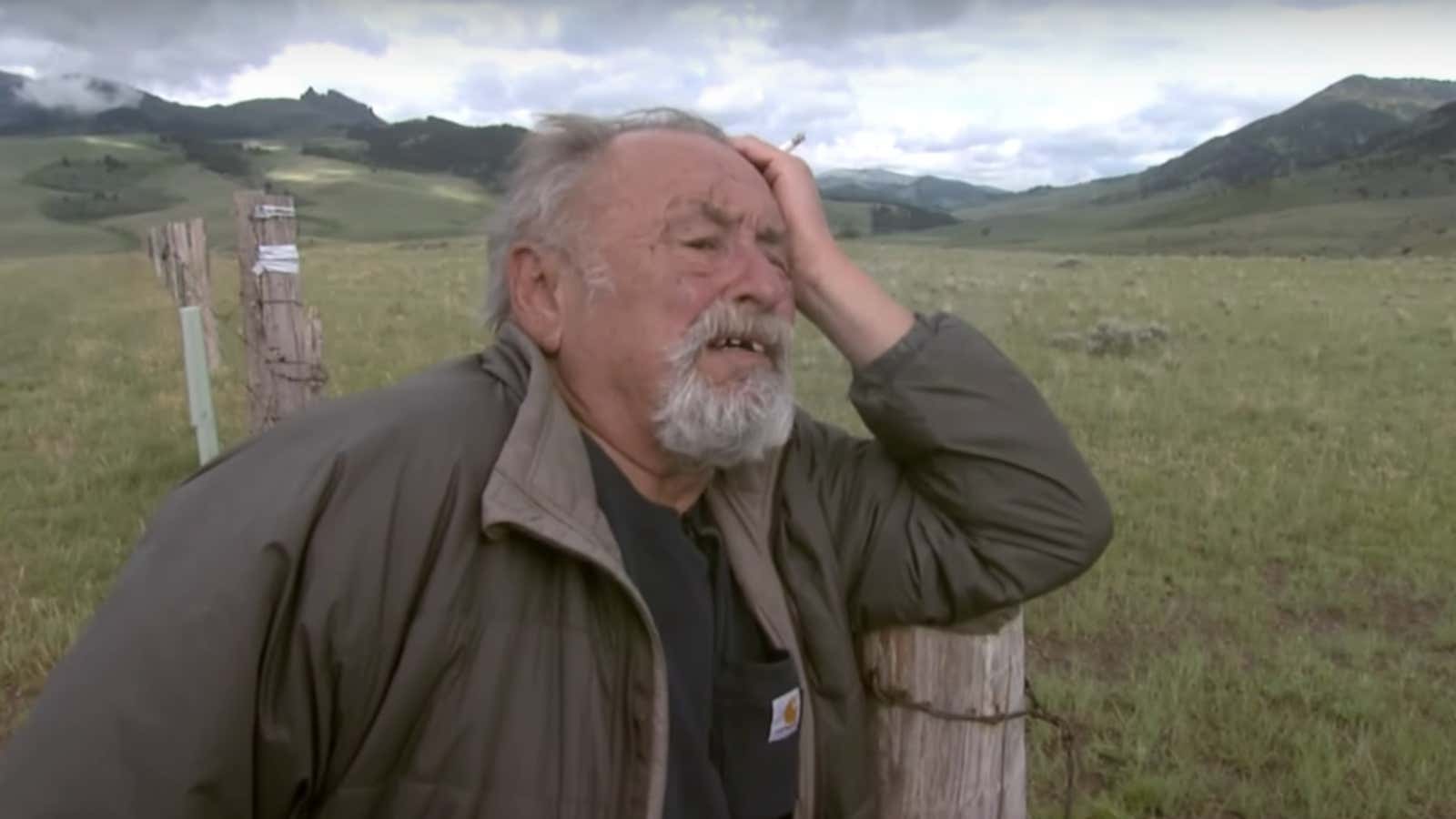

In 2008, at a particularly disorienting time in my life, I set out West in order to see a part of America that had obsessed me since I had read Jim Harrison’s novella Legends of the Fall in 1994. Jim’s writing had obsessed me equally, and the trip turned into a pilgrimage–driving through Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, where Jim had had a writing cabin for many years, I happened to stay with some people who knew him, and Jim was kind enough to answer the phone when I called. (Jim was renowned for his writing and epicurean living, but it’s less known what a gracious, generous spirit he was.) We spent parts of two days talking in his new hometown of Livingston, Montana. I confessed all my anxieties about the work I felt called to and kept dodging. He sent me off with lines from a poem: “Be true / to your strange kind.”

I had meant to, and failed to, write about that experience ever since–my memory of it was powerful, but episodic, as I hadn’t taken notes. And then Jim died–last week, at 78. That night, I opened again a collection of his poems called Letters to Yesenin, written in 1973. Sergei Yesenin, the great Russian poet of the early 20th century, committed suicide in 1925 at 30, and Letters to Yesenin is Jim–who was then living on a farm in northern Michigan with a wife and two young daughters, trying to scratch out a living as a poet–working out how to step back from the same edge. He wrote it at more or less my age (I’m 37, he was 36), and through it somehow got himself living again. (“My year-old daughter’s red robe hangs from the doorknob shouting Stop.”) I had looked at that slim book a dozen times, but it was only that evening that it occurred to me how my recollections of Jim could be enough. I’m not a poet, but I think Jim would forgive me.

1.

I’m not much of a poet.

I wrote a poem once,

And was proud of it the way

A teenager is proud of a kiss —

You have no idea what else you could do with that mouth.

All I remember is my grandmother was in it,

worrying a bowl of hot soup with her lips.

The teacher, a famous old poet,

himself now recently dead, said:

“This poem reads as if no one

has ever written a poem about grandmothers.

And I don’t mean in the good way.”

I’ve learned humility since, and

where I missed my chance, life

has helped.

I adored you without humility.

I was given a mind without clean lines,

so I used you for all that I could.

I took you like medicine.

An old analyst — I prefer old people, it seems —

Said to me once: “The most important thing is to hope.”

So I used you for that.

You wrote to Yesenin in 1973.

Fifteen years later, I was ready

To start him in school when my parents took me out

And put me down in Brooklyn —

A condition that required me to write you

Twenty years later.

Your own mind had to speak for Yesenin,

But you answered me.

I wonder what you’d say now.

You’d say: “The thing about heaven

is you never get full.”

2.

I’ve been trying to write this

for eight years.

Like you, I work.

Nothing’s taken eight years

except a failed love once,

but it was worth it.

I wanted to do it before you went.

I was thinking of publication, of news pegs.

(In this building, ring the top bell for

Romantic

And the bottom for Mercenary.)

But I have not known how to say it.

I — whom you picked up, dusted off, and sent the same way, but with a father’s assurance.

I — who have too many words.

When I searched for you, I didn’t take notes — I was less

Mercenary at that time. I was busy

thinking about how to survive,

not write books.

(Old codger to young fool:

That’s how you survive.)

Two novels yielded

In the time I failed to write about you.

What were you saying to me?

You wished me to have some kind of faith?

I have a peasant’s faith, a Jew’s faith, an immigrant’s faith: Nothing outside myself.

I surrendered, you know.

Not long ago.

It’s like checking your heart about lost love —

one day, you are skinned over.

This headache will never become diagnosed.

In my second novel, a woman had given up: “Truthfully,

I was relieved. A fear went out of me.

I thought: So I will not get to do that.

It was like saying good-bye

To a complicated lover.

The love went,

but so did the heartache.”

Then you died.

After I heard, I heated some food and took care of small things.

Why?

Ten hours later, I opened “Letters to Yesenin.”

And with it this answer.

In my first novel, the hero’s grandmother dies

Before he can persuade her to talk.

Are we not our personal soothsayers,

Even as we fail at work, life, and love?

I will forget this tomorrow.

You will remind me.