There’s no avoiding it. Work an eight-hour day (or longer) and you’ll have to stop to eat at some point. Be it a questionable sandwich or a lavish lunch, workers need grub. But what should you eat to achieve maximum results? And is skipping lunch to polish off that email really such a bad thing?

Here’s the Quartz ultimate guide to eating at work:

Eating in the office canteen is good for you. In Finland, at least.

The Finnish have done a lot of research into workplace eating habits. One study by the Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare found that workers who ate in office cafeterias, compared to those who brought in packed lunches, were eating more fruit and vegetables. This has a lot to with the fact that in Finland, food provided in canteens must meet national nutritional guidelines.

In the US, a study by the Society of Public Health Education found that the number one source of food workers were bringing into the office was fast-food joints. The same study also found that if healthy food was provided on site, workers were more likely to make healthier choices.

To be sure, the wisdom of eating in a canteen does depend on the quality of what’s on the menu. Staff interviewed at Barnsley Borough Council in London described the food in their cafeteria as “stodgy” and more suited to manual laborers.

Skipping lunch is bad for you.

As explained in his book about workplace eating habits, Christopher Wanjek found that workers who skip lunch are more stressed, less productive and only end up snacking in the afternoon anyway.

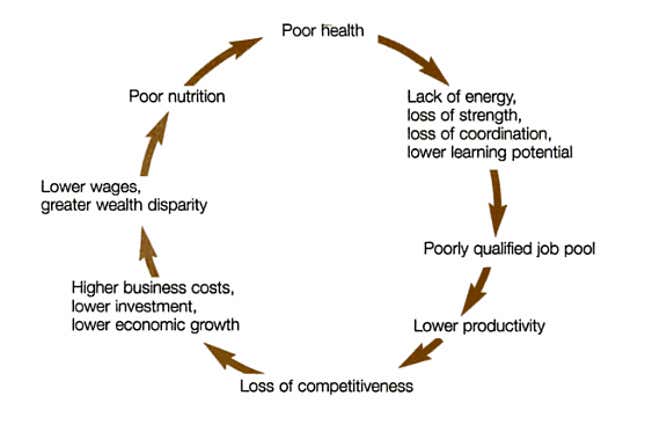

The endless cycle of bad nutrition and low national productivity

Poor eating choices impact productivity. In fact, it causes this shame spiral:

What’s the deal with superfoods?

In the nineties, it was all about organic food. Then along came the concept of “superfoods,” a term used to describe foods that are supposedly really, really good for you. But it turned out to be more of a re-branding exercise for otherwise fairly mundane supermarket produce, like berries. And if you ask a scientist, the term superfood actually means something completely different. It’s used in academia to refer to calorie-dense food, like chocolate.

There is sufficient evidence, however, to support consuming things like honey, salmon, soy, lean red meat, cinnamon and green tea because of the positive effects they have on health and, ergo, productivity (see chart above).

Broccoli is also definitely good for you.

But there’s simply no such thing as a miracle food. It’s best to load up on as many different types of fruit and vegetables, lean meats and low-fat dairy (if you eat those), and legumes (pulses, such lentils and beans) as possible.

Eating well: whose responsibility is it, anyway?

When surveyed by researchers from Nottingham University, staff at the UK’s National Health Service said they felt they had a responsibility to set an example for healthy eating at work. But the American Journal of Public Health found that for healthy eating habits at work to take any effect, workers’ families also had to get on board. What people eat at work is linked to their overall lifestyles and attitudes to nutrition. Since many people (especially manual workers) bring food from home prepared by a partner, educating the family is all the more important.

And Wanjek makes a case for improving the street food on offer—particularly in developing economies—so that people have inexpensive, nutritious options near their work. Using a case study from South Africa, Wanjek outlines how government intervention led to tighter regulations on vendors, in turning improving their safety standards. Vendors in the Guateng province, where this project took place, became reliable sources of affordable food for workers stopping by on their lunch breaks.

The desktop dining debate

Roughly 70% of Brits and 67% of Americans eat lunch at their desks. But is this such a bad thing? Two Slate writers slung this one out. Inspired by her time working in France, Rachael Levy wants us to take a cue from the French when it comes to taking lunch breaks. She argues that taking the time to have lunch away from the office makes you a more productive, happier worker.

Rachael Larimore told her to back off and let her eat her sandwich, at her desk, in peace. Larimore said she’d rather forfeit her lunch hour and snaffle her sandwich while plowing through her work so that she can finish a little earlier to spend more time with her family.

Of the two Rachaels, Levy’s probably right. Research from the University of California-Davis has found that powering through a lunch break, especially on a thought-intensive task, hinders performance. Letting your brain “rest” in your lunch break can help recharge your creative capabilities.

Go easy on the booze at the office party.

The booze might be flowing at the office party, but so are the lewd comments. Researchers at Cornell University conducted a study that found when people drink in or around the workplace, harassment is more likely to take place. In offices which turn a blind eye to drinking during working hours, women are twice as likely to experience “gender harassment,” or aggressive and offensive remarks made by fellow colleagues.

Employers should help staff lose weight.

Research has found that overweight workers run up big costs to employers. After studying work-related injuries at one of their facilities in Texas, researchers at Shell Oil found overweight employees to have a 50% greater risk of injury than their average-weight colleagues. Sick leave and health-care costs also stacked up higher among these employees. Anti-smoking campaigns in the workplace have been a success; researchers are now encouraging employers to implement weight-loss programs. Just imagine the poster campaigns.