Why the sweaty, crowded summer festival became the last sacred space in music

Utter chaos is about to break loose in Indio, California.

Utter chaos is about to break loose in Indio, California.

The sleepy desert town—home to barely 75,000 people—is gearing up to host Coachella, a week-long musical bacchanal notorious for glitzy feats and none-too-low levels of pretension. Coachella’s success is the envy of all live events; the festival has broken its own profit record for the last four years, raking in a cool $84 million in 2015. It’s getting so big, Indio’s council just approved an extra 25,000 tickets to be sold in 2017.

What’s funny is that Coachella is not that different from Lollapalooza, Eaux Claires, Warped Tour, Austin City Limits, and the literally hundreds of other festivals offered across the world each year. We looked at the lineups for 11 major festivals that will take place across the US this summer and found a surprising amount of overlap. Below, for instance, is a list of musicians slated to play at three or more of the 11 shows.

(On mobile, turn your phone sideways to see full list of festivals.)

N.B. We used data from the original lineup announcements, and as festivals frequently add new acts in the months afterward, the real overlap is actually even higher.

According to Nielsen, 32 million people went to at least one music festival in the US in 2014, and the average distance traveled to attend them, including by those who flew overseas, was 903 miles. Such wild demand for what’s become the quintessential festival experience—that is to say, days on end of music, booze, and general revelry—has led to a recent explosion in new festivals.

Why are festivals booming now at a time when the music industry is half the size it was in 1999? And what does their growing sameness say about their future?

Top of the pyramid

One way to think of it is as a counter-trend to the coldness of music streaming. What we all want—actually, what we’re craving—is an authentic, individualized experience.

Digital streaming services—Spotify, Apple Music, Tidal, Deezer, and a scattering of smaller players—are officially the biggest revenue-driver of the entire music industry, according to figures from the Recording Industry Association of America.

The abundance and affordability of streaming subscriptions—which seem almost too good to be true, with their offers of ad-free, unlimited music catalogs for less than $200 a year—have won consumers’ approval, and more people are signing up for streaming every day.

Here’s the thing, though. Deep down, on a very basic psychological level, we’re all exclusivity snobs.

“Because music has become very accessible to everyone, music has become something very utilitarian—it’s lost the experience around it,” says Bas Grasmayer, a digital strategist for music businesses.

The services offered by Spotify and its competitor platforms are all passive—users can simply pick a playlist and sit back, losing out on the engagement that used to come with discovering music on obscure websites or going out to buy your favorite band’s new CD. In essence, music has become background noise.

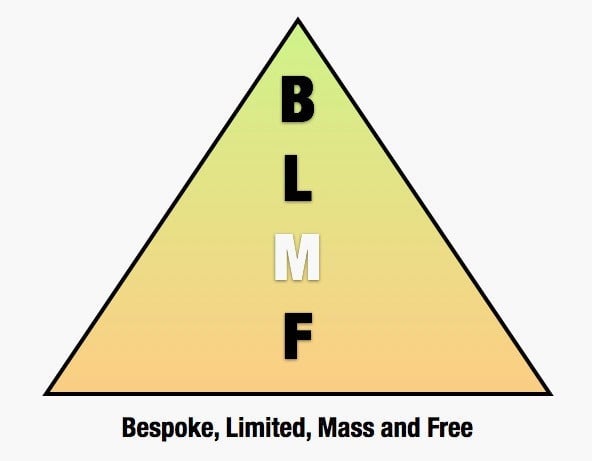

So listeners are turning elsewhere for the special features, and for that extra level of intimacy. As entrepreneur and marketer Seth Godin suggests, there exists a pyramid for every form of media: at the wide bottom is whatever is being offered on a mass scale, and the higher you go, the more exclusive—and thus coveted—the offering.

The “limited” tier—described by Godin as “a seat in a Broadway theater, attendance at a small seminar, or a signed lithograph”—is what consumers crave after they get their fix of whatever’s free and mass-produced.

And right now, that highest tier is live events, of both the single-artist concert and Coachella-esque festival variety.

And the more unique and interesting the concert, edging toward Godin’s ultra-elite “bespoke” tier, the more fans go crazy. Tickets for a one-time Bad Boy reunion concert by Puff Daddy at a New York arena recently sold out within seven minutes, for example. This is also why music festivals, which take place only once a year in specific locations and typically only in the weather-convenient summertime, are seeing so much traffic.

“There is a growing, insatiable appetite for things that are meaningful, for the experience of being recognized,” Owen Grover, senior vice president of streaming and live events business iHeartRadio, says of music consumers at large. Since paying to spend an entire one-on-one day with an artist isn’t something most people can afford, live shows, which may be crowded but still intensely personal, are the next best thing to satisfy that appetite.

Too much, too soon?

There’s no need to fret if you can’t make it to Coachella, though, because there are an astonishing 173 music festivals in the US alone this year.

New ones won’t stop cropping up—to the point that festivals have started pitching fits to local governments about each other. So fierce is the battle, live-events businesses are even teaming up to pool their resources. Just this week, Governors Ball Music Festival parent company Founders Entertainment announced a partnership with concerts company Live Nation, saying the latter’s extended reach is essential for the company to remain competitive. Jay Z’s Tidal this week also created a surprise three-day festival of African music with no warning, likely trying to appeal to people who want to be seen as spontaneous and in-the-know.

And that’s a new kind of problem—as demonstrated by the fact that all music festivals are starting to look the same. If live music is meant to be an exclusive commodity, what happens when there are suddenly hundreds of similar events to choose from?

Coachella’s parent company AEG recently wrangled approval to launch a brand-new music festival that will take place inside California’s Rose Bowl football arena—a controlled, organized, sanitized Coachella lite.

Perhaps the fact that even festivals—just like streaming companies—are now straining to differentiate themselves is a sign that oversaturation is indeed coming. It might just be a matter of time before fans realize this and move on to a more exclusive thing, whatever it may be. Music is a fickle place.