In 2015, Katharina Unger, 25, and Julia Kaisinger, 28, packed their bags and flew from their native Austria to Shenzhen, China’s electronics manufacturing hub, and formed a company called Livin Farms. Their flagship product—a counter top machine that raises live worms you can harvest and eat at home.

“I wanted to create a way for people to independently grow their own protein using minimum space in their home,” says Unger. “I grew up on a farm with cows and animals. But raising insects requires less space, and is cleaner than raising animals.” She and Kaisinger are using the $145,429 they raised on Kickstarter to finance the product’s development.

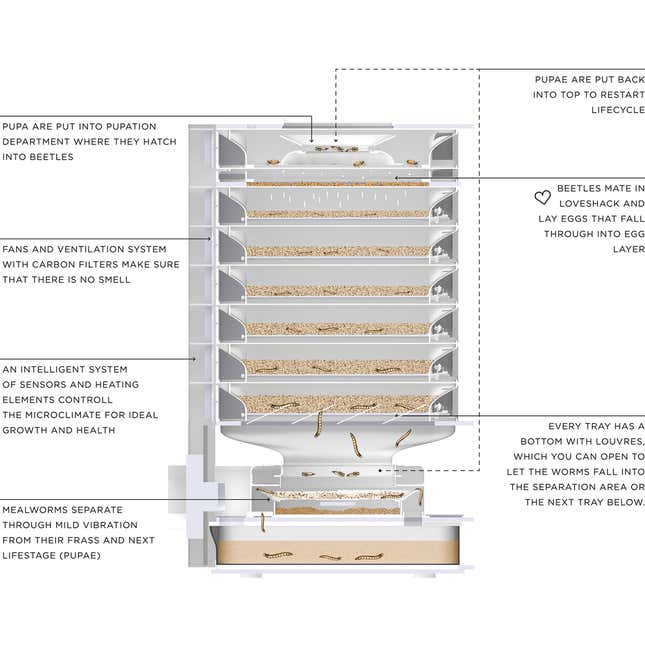

Dubbed the Hive, Unger and Kaisinger’s device consists of a series of trays. Users place live beetles, which will come shipped with the device, in the topmost tray. Their eggs filter through a mesh bottom into the tray below. As the baby mealworms hatch, they filter to the next lowest tray. This process continues for each phase of the mealworm’s life cycle using a system of vibrators, sensors, and manual levers to move bugs from one tray to another.

Users feed the worms vegetable kitchen scraps.

Once the live worms are mature, they’re removed from the trays, or “harvested.” After freezing them, they can be fried, baked, boiled, or ground into a powder.

Shenzhen or bust

Unger and Kaisinger don’t speak Mandarin. They have no ties to Asia except for Unger’s brief stint at a design firm in Hong Kong. But Shenzhen was the logical place to relocate after they raised money. The southern Chinese city has changed the speed at which new consumer electronics are produced, thanks to an ample supply of engineers and and factories. Pipe dream ideas (or bug-raising countertop hives) can turn into physical realities overnight. The hoverboard, for example, went from an engineer’s basement project to a billion dollar industry in months—all thanks to a bevy of Chinese suppliers, assemblers and exporters that jumped on the trend.

Unger and Kaisinger are alumni of Hax, a Shenzhen-based program and venture capital fund that helps foreign hardware startups source components from China. They share office space with companies building niche products like a wristband that tracks every time you bite your nails or twirl your hair, or a CNC milling (or “3D subtraction”) machine that uses a jet of water to carve out objects.

Unger and Kaisinger are currently completing Hive’s working prototype. They say working from Shenzhen helps them meet component vendors and test parts faster than if they remained in Austria. It also helps them ensure the factories they hire are committed to sustainability—something that the team values.

“I can’t imagine being abroad and communicating with the manufacturers we work with,” Unger tells Quartz. “If we weren’t in Shenzhen we would have to place an order, get it shipped to Europe, and would have no idea how it works, or what the working conditions in the factory are like. But by being based here we can actually go over there ourselves to make sure the products are quality, sustainably sourced, and that the working conditions are good.”

Why mealworms?

Research supporting bug eating as a better source of protein has been well-publicized. In 2013, The UN issued a lengthy report on the benefits of eating insects, noting they’re cheaper to raise and more energy efficient than other animal proteins. For every 1 hectare of land that can produce mealworm protein, 2.5 to 10 hectare would be required to produce an equal quantity of beef protein. They also emit fewer greenhouse gases while raised.

Most of the businesses at the forefront of this movement revolve around disguising bugs in “normal” food. Chapul, for example, makes cricket flour that you can sneak into protein bars, cookies, or smoothies. Unger and Kasinger aren’t trying to be so discreet.

“Our target customers they really want to know what they eat,” says Unger. “They want to be independent, and they want to have high quality nutrients and proteins. Insects are a good way of putting your kitchen scraps into the system and harvesting quite a lot of high-quality food.”

Tastes like…shrimp

I’m more of a “purchaser” than a “harvester” when it comes to food. But I’ve never been one to turn down a taste test challenge. When Unger and Kaisinger offered me a spoonful of fried mealworms, I dutifully obliged.

Fear not—fried mealworms are not disgusting. In both flavor and texture, they resemble dried shrimp—a common topping on noodle dishes in China. When chewed, the mealworms’ shellfish-esque flavor grows more pronounced. A subtle, nutty bitterness emerges. Unger and Kaisinger recommend mixing them in with yogurt, like granola. I’d recommend taking baby steps. Break them down into crumbs so they don’t look like worms, and then sprinkle them onto stir-fried vegetables.

Unger and Kaisinger are hoping to enter mass-production of the first batch of devices in June. In November, a finished product will finally hit the doorsteps of the company’s Kickstarter backers. The two priced the device at $649—a price likely limited to appeal only to the most dedicated, adventurous sustainability obsessives. But those consumers are out there somewhere. So are the Chinese factories that are capable of serving them. Home grown bugs-on-a-plate might never be as popular as the hoverboard, but they’re closer to reality than before.