Few purchases are as fraught as a diamond engagement ring. Frequently the most expensive accessory we ever buy, engagement rings carry the totemic weight of representing one’s love and commitment, and are meant to be timeless in their perfection as we gaze upon them forevermore. And yet, although the sellers of those diamond rings can rhapsodize endlessly over a ring’s design and the cut, clarity, color, and carat size of the rock inside it, it’s rare that they disclose that diamond’s origins. This despite the relatively common knowledge that diamonds have helped finance unspeakable violence in war-torn countries, lined the pockets of corrupt billionaires, and wreaked environmental havoc all over the world.

All that said, many of us still want diamonds. You can blame the 20th century’s most successful marketing campaign, but even without the hype, the stones still evoke natural wonder, have a sparkle all their own, and damn if they aren’t durable.

The diamond industry is notoriously shadowy, but aggressive consumers can shop for engagement rings with the same informed and holistic approach they might take to, say, fair-trade coffee or organic produce.

Here, some tips and sources for shopping for a symbol of everlasting love that’s not diminished by having caused harm elsewhere.

Don’t trust dubious certifications

For starters, ask a ton of questions. Then, ask more questions. The diamond industry will only become more transparent if consumers demand it.

Most jewelers and diamond dealers will say their diamonds are “conflict-free,” citing their Kimberley Process certification, an international protocol designed to keep conflict diamonds (also known as blood diamonds) off the market. The truth is, the Kimberley Process protects diamond dealers and consumers from discomfort far more effectively than it protects the residents of diamond-rich, war-torn countries.

Its definition of a “conflict diamond” is outrageously narrow: “rough diamonds used by rebel movements to finance wars against legitimate governments.” As Ian Smillie, an authority on conflict diamonds, told Time, that means that diamonds from mines in Zimbabwe, where the army massacred more than 200 workers, were not “conflict diamonds,” as defined by the Kimberley Process.

“Thousands had been killed, raped, injured and enslaved in Zimbabwe, and the Kimberley Process had no way to call those conflict diamonds because there were no rebels,” said Smillie. It similarly failed to identify gems mined under abhorrent conditions in Angola as “conflict diamonds,” because they were mined in government-controlled territory.

And even when the Kimberley Process does suspend diamond trade from a member country—as it did with the Central African Republic in May 2013—smuggling still happens. The United Nations estimated that some $24 million worth of smuggled diamonds were smuggled out of the country in the 18 months following the suspension. Theoretically, a smuggled diamond from the Central African Republic could receive a Kimberley Process certification in an approved country, and re-enter the “conflict-free” diamond supply. Diamonds often change hands several times over before they ever get to the client-facing dealer or jeweler, so it’s incredibly difficult to know where a a stone actually came from.

But don’t despair! There are ways to find diamonds with clearer pedigrees, some of which will even deliver more bling for your buck.

Find a diamond with an origin story

The first question to ask about your diamond is where it came from. Brilliant Earth, a San Francisco-based jeweler that sells engagement rings online and through its showrooms in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston, specializes in bringing more transparency to the process, and allows customers to search for diamonds according to their origins. (It’s in the “advanced” option.)

The company sells diamonds mined in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Canada, and Russia, as well as their lab-grown counterparts (more on that to come), and donates 5% of its profits to development projects in communities impacted by diamond mining, such as a Botswana-based mobile education program designed to give children at risk of being sent to work in mines a leg up in their education.

“Some customers are drawn to a particular origin, usually through a personal connection to the region or a preference with regard to their practices,” said Kathryn Money, who oversees strategy at Brilliant Earth.

Many customers choose diamonds from Botswana—the world’s second-biggest diamond-supplying nation behind Russia—because agreements with the government there have funneled some diamond profits into education, healthcare, and infrastructure projects. Those diamonds come from Diamond Trading Company Botswana, a joint venture between De Beers and the government of Botswana.

Although the diamond trade has brought some development and infrastructure to Botswana, experts lament that it has done little to repair the country’s vast inequality, and has also tied the country’s economic health to a volatile market. And while most DTCB diamonds come from Botswana, De Beers also sends Namibian, South African, and Canadian diamonds to its Botswana-based sorting facility.

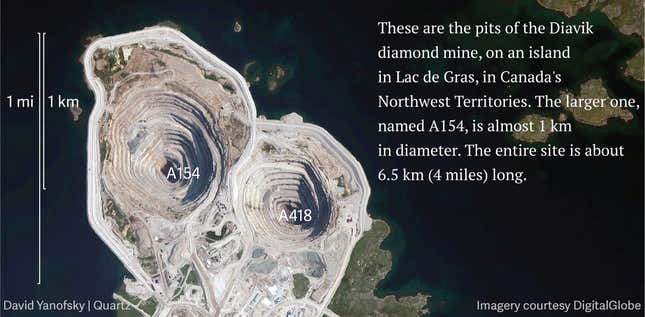

Consumers discomfited by the cloudiness (and proximity to conflict diamonds) could opt for a Canadian diamond. Stones from CanadaMark—sold by Brilliant Earth and elsewhere—come with a serial number and verification that the diamond is indeed of Canadian origin. The operators of the Diavik and Ekati mines, where CanadaMark diamonds are sourced, hires and trains workers from local Aboriginal communities (they reported that 18% of operational employees were Aboriginal in 2014), donates to local scholarship funds, cites strict adherence to environmental laws, and powers 10% of one mine with renewable energy from a wind farm (pdf).

All that said, there’s no getting around the staggering scale of an industrial mine; there’s little that’s romantic about it.

“Development diamonds” are coming

While there is such a thing as “artisanal mining”—also known as alluvial mining, or quite simply, digging—the companies that can currently afford to vouch for their diamonds’ origins tend to be massive multinational mining outfits. But what if a person wants to support a smaller operation in the developing world?

A program called Diamond Development Initiative (DDI) is underway to help register, organize, train, and support artisanal and small-scale miners—often the most vulnerable to violence and exploitation—in places such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Sierra Leone.

“We envision ‘development diamonds,’ as diamonds that are produced responsibly, safely, with respect of human and communities’ rights, in conflict-free zones, with beneficiation to communities and payment of fair prices to miners,” writes DDI.

DDI plans to have its first rough diamond sale in a few months, offering its rough gems to the trade.

Old trumps new

Call them up-cycled, recycled, estate, vintage, or antique. The market is rife with old diamonds, many of them more beautiful and unique—and less expensive—than their newly mined, machine-cut counterparts. Of course it’s true that these stones may have been associated with less-than-perfect practices in their past, as Jared Holstein, a partner in Perpetuum Jewels, a New York and San Francisco-based wholesaler of estate jewelry and gems, pointed out.

“We…never include the word ‘ethical’ in relation to our stones,” said Holstein. “It’s entirely possible they were mined or procured in way we would today not find acceptable…We can’t change a stone’s past. It’s likely the cotton in the pieced quilt stitched by you great-grandmother was harvested by slaves or sharecroppers, as possibly was the Indigo that made its blues blue.”

All that said, investing in a recycled stone will keep your dollars from perpetuating new mining, with its human and environmental consequences.

Most jewelers will be happy to work an up-cycled stone into a ring for you. Many will even help you find one.

“I personally love antique diamonds,” said jeweler Anna Sheffield, who designs rings to enhance their unusual cuts at her downtown Manhattan studio. “They’ve been mined already. They already exist. Why get a modern stone that’s been turned recently, when you can find something of equal magnificence that’s already been cut by human hands?”

Sheffield favors old European-cut diamonds, a style typical of round stones dating back to the period between the late 1800s and 1920s. Back then, diamonds were cut to dazzle in low-light conditions such as candlelight, which resulted in deeper diamonds with facets that reflect less light—but more color—than their modern counterparts.

“You see more of a kaleidoscopic thing happening, and not just a super-sparkler,” said Sheffield. “It’s just far more unique.”

Some of those old-fashioned cuts, says Sheffield, can even have the appearance of a larger stone. Rose cuts, for instance, tend to be shallower with wider faces.

“You can get the look of a one-carat from above,” said Sheffield. “But the cost will be far less.”

Choose a diamond that wasn’t dug from the earth at all

Some call these diamonds ”synthetic,” but unlike diamond alternatives such as cubic zirconia or Moissanite, lab-grown diamonds are atomically identical to those born in the earth’s mantle.

When I took a half-carat dazzler that was grown in a reactor at Diamond Foundry, a Silicon Valley startup, to New York City’s diamond district, no dealer could distinguish the difference (though once I told them the origins, one cut his estimate of the stone’s value in half).

But here is one major difference from an ethical point of view: With a diamond grown in a lab, consumers can be sure their stone didn’t contribute to the environmental and human costs associated with natural mining, and can be absolutely certain of its origins.

“[Lab-grown diamonds are] a perfect choice for a consumer that’s looking to minimize the environmental impact of their purchase,” said Money, who also offers them in addition to mined diamonds at Brilliant Earth. “They have the same sparkle, scintillation, and fire as a natural diamond.”

Both Diamond Foundry and Brilliant Earth allow shoppers to buy loose diamonds—should you want to work with your own jeweler on a custom design—as well as rings made-to-order. In Diamond Foundry’s case, those come from several independent jewelry designers collaborating with the company.

Don’t forget about the metal

Like diamonds, metals such as gold and platinum are associated with both human and environmental devastation that includes erosion, contamination, and deforestation. Earthworks, a nonprofit organization, estimates that the gold required for a single ring generates some 20 tons of waste, much of which contains mercury and cyanide that ends up in local water sources and marine environments.

Finding recycled gold isn’t as difficult as you might think. Again, you just have to ask. The New York-based designer Bliss Lau crafts stunning, modern styles crafted from recycled gold, as does Monique Péan, along with all of the aforementioned sources: Anna Sheffield, Diamond Foundry, and Brilliant Earth.

These ethical quandaries may seem overwhelming at first, but to find the right ring will inevitably require many questions. Consider a few more an additional investment in a ring that you—or your loved one—will feel good about for a lifetime. You could even help improve the industry along the way.

It’s time to get engaged.