China’s investment-heavy growth model might make investors assume its energy companies would be well-positioned for profits. In fact, Chinese energy companies are being forced to look overseas to offset their woeful businesses at home.

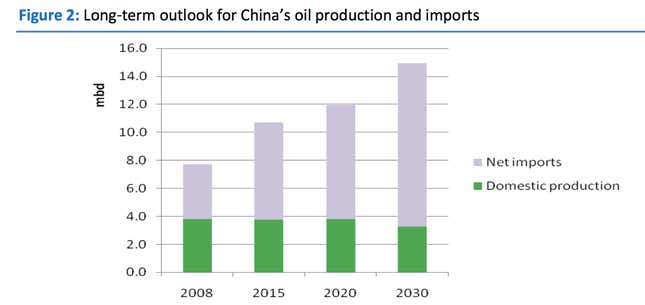

China is nowhere near self-sufficient in energy, so companies like PetroChina and Sinopec must import much of the country’s oil. They’re also highly vulnerable to fluctuations in world energy prices, unable to pass on increases to consumers because of government price caps.

When refiners’production costs are higher than mandated petrol prices, the red ink can add up fast: Petrochina just posted a staggering 34 billion yuan ($5.5 billion) operating loss (pdf p.16) in its domestic refining business last year, contributing to a 13.3 percent drop in 2012 net income (pdf p.3). State-owned oil producer Sinopec was in similar straits, as 2012 net profit fell 12.1% (pdf p.3).

Sinopec, PetroChina and their state-backed stablemate Cnooc have been snapping up foreign assets for over a decade. Cnooc, whose net profit fall 9.3 per cent, paid more than $15 billion to buy Canada’s Nexen last year.

Chinese acquisitions of overseas energy assets is often assumed to be mostly about helping the Beijing government secure oil and gas supplies for domestic consumption. But Chinese energy companies also want to reverse their financial fortunes by selling the oil and gas they produce overseas on world markets, competing with the likes of BP or ExxonMobil and mitigating their heavy losses from domestic refining.

The International Energy Agency predicts that by 2015, Chinese state-owned companies will produce an amount of oil outside China’s borders that is equal to Kuwait’s annual output. The IEA found in this 2011 report(pdf p.7) that China’s state-backed energy firms have been opening trading offices in world financial centers such as London and New York, and that oil from a pipeline PetroChina’s government parent, CNPC, has built in Kazakhstan was “being sold on the international market” (p.18).

Quartz also reported earlier in March that Chinese companies are trading much of the oil they buy from Venezuala, instead of sending it home.

Yet whether the Chinese majors can parlay their foreign acquisitions into overseas trading profits remains to be seen. Chinese energy firms sometimes overpay wildly for overseas assets, enabled by cheap credit from domestic banks. And having only recently positioned themselves as global energy traders, they still lack the marketing, political and technical expertise an energy multinational needs to be taken seriously.