“Whatever the present position of India might be,” wrote Jawaharlal Nehru, “she is potentially a Great Power.”

Barely three days earlier, on 2 September 1946, Nehru had been sworn in as the vice-president of the viceroy’s Executive Council—effectively prime minister—in a Congress-led interim government. Now, he was telling the Ministry of External Affairs why India must aim to be elected as a non- permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. “Undoubtedly,” continued Nehru, “she [India] will have to play a very great part in security problems of Asia and Indian Ocean, more especially of the Middle East and South-East Asia. Indeed, India is the pivot round which these problems will have to be considered . . . India is the centre of security in Asia.”…

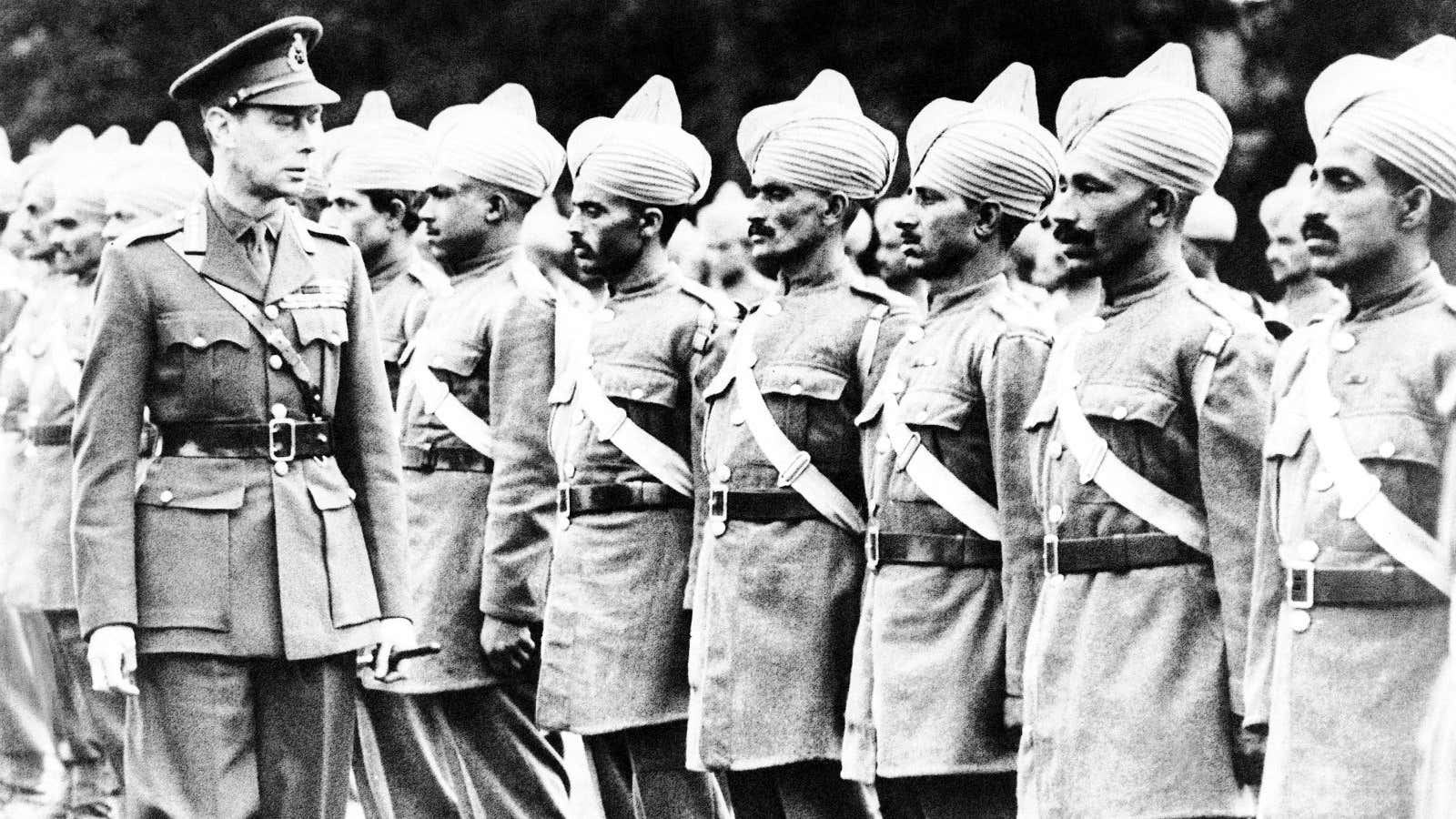

Even as Nehru sought to position India as a major regional power in Asia, the Indian army was undergoing rapid retrenchment. Soon after the war ended, GHQ India expected the army to shrink from 2.5 million men to 700,000 by the end of 1946. This entailed, in the first instance, a major exercise in repatriating soldiers from various theatres back to India.

Between the Japanese surrender and the end of April 1946, some 600,000 men and officers were demobilized at an average rate of 70,000 to 80,000 a month, and around 2,000 units were disbanded. If demobilization was slower than anticipated, it was not only due to the massive logistical challenges of bringing troops home. Rather, it also reflected the continuing military demands on India.

In April 1946, the Indian army still had two brigades in Middle East; four divisions in Burma; three divisions in Malaya; four divisions in Indonesia; one division in Borneo and Siam; a brigade in Hong Kong; and two brigades in Japan. Over the next few months, repatriation and demobilization gathered pace. By October 1946, the Indian army had 800,000 men and officers. By April 1947, it stood close to 500,000 strong. So, as independence approached, India’s ability to project military power in Asia was increasingly circumscribed…

Secondly, the war had led to overt militarization of a large chunk of the population. The manifold expansion of the Indian armed forces provided military training and combat experience to hundreds of thousands of men.

On demobilization, they joined in droves the self-defence units and volunteer outfits of all communities that were mushrooming in post-war India. To these outfits, the former soldiers brought their professional skills in the organized application of force and the ability to impart basic training to other recruits. Those with combat experience were not only inured to the idea of killing people but capable of improvising in rapidly changing and violent circumstances. Nor were the skills that they had picked up during the war restricted to using force.

The organizational techniques learnt in the military enabled them to construct safe-havens for their communities and ensure safe passage through hostile territory…

Indeed, during Partition, the districts that had higher numbers of men with combat experience saw significantly higher levels of ethnic cleansing.

By contrast, the capacity of the state to halt the violence had considerably diminished. Not only were the armed forces wracked with a host of troubles, but they too were being partitioned between the new states of India and Pakistan…

The legacy of the Second World War coloured the first India-Pakistan war over Kashmir in other ways too. For instance, the crucial airlift of Indian troops to Srinagar on 27 October, which stopped the Pakistani raiders in their tracks, owed a great deal to the techniques and capabilities honed during the battles of Imphal and Kohima.

Both armies fought using American as well as British weapons and equipment, and when the United States imposed an informal embargo on supplying arms and spares to India and Pakistan, both countries were forced to use their shares of the sterling balances to import military equipment from Britain. Nevertheless, India was the principal beneficiary of the wartime expansion in ordnance factories and strategic infrastructure—most of which had occurred outside the areas that became Pakistan—for Allied operations against Japan. Not surprisingly, Pakistan sought to offset its military weakness by seeking an ostensibly anti-communist military alliance with the United States.

By the time the First Kashmir War ended in December 1948, India and Pakistan were locked in a rivalry that persists to this day. Interestingly, one of the few acts of co-operation between them was the formation of a combined historical section to write the official history of the Indian army during the Second World War. Yet this was a history that neither country wanted much to recall…

Modern South Asia remains a product of the Second World War. The Partition of India might have been inconceivable without the stances and policies adopted by the Raj, the Congress and the Muslim League during the war.

Equally important was the sundering of India’s links with its eastern neighbours. The ‘Great Crescent’ stretching from Bengal to Singapore via Burma, Thailand and Malaya, was shattered by the devastation of Burma in war and by Britain’s unwillingness to invest in its reconstruction in peace. As Burma embarked on a prolonged period of introversion and international isolation, India’s geographical and economic, cultural and strategic links with SouthEast Asia were broken.

The cumulative impact of these developments, against the backdrop of the emergent Cold War, put paid to Nehru’s vision of India as a regional hegemon that could don the mantle of the Raj. India’s strategic horizons narrowed to its immediate borders and it proved incapable of exerting any real influence in the Persian Gulf, East Africa or South-East Asia. Instead, India had to fall back on claims to solidarity with, and leadership of, the still-colonized countries–and subsequently the Third World and non-aligned nations.

Not all the consequences of India’s war were deleterious. Popular mobilization during the war led to a widening of the political horizons of the Indian peoples. Ideas of freedom and democracy, social and individual rights seeped into the discourse – not just of the elite but also of the marginalized. This underpinned the subsequent decision of the Indian Constituent Assembly to adopt a universal adult franchise and provide for economic and social as well as political rights…

Perhaps the most pressing reason to recall India’s Second World War is geopolitical. Today India stands again at the centre of an Asia whose eastern end is unsettled by the rise of a new great power and whose western end is in the throes of ideologically driven turmoil. To be sure, the situation now is very different from that of the early 1940s. Yet India is seen as a key player in ensuring a balanced regional order in East Asia.

And India’s own dependence on oil, as well as the presence of a large diaspora, impels it towards a more active role in stabilizing the Middle East. Yet if India is to revert to its older role as the ‘pivot’ of Asian security, it will first have to aim at the economic and strategic integration of the subcontinent: both to its west with Pakistan and Afghanistan and to its east with Bangladesh and Burma.

Only then can the rise of India—prefigured in the Second World War—be fully realized.

Excerpted with permission from Penguin from India’s War: The Making of Modern South Asia, 1939-1945, authored by Srinath Raghavan. We welcome your comments at ideas.india@qz.com.