CY Leung is one of Hong Kong’s homegrown treasures, and we should embrace him

Hong Kong

Hong Kong

We are living in a golden age of Hong Kong creativity.

Yes, chief executive Leung Chun-ying might be the least popular leader the city has ever had. But to this Special Administrative Region of China once deemed a cultural desert, this controversial man has had an important, unexpected impact.

“Leung is a very captivating figure in a sense that he has unleashed the creative power of Hong Kong citizens,” said Oscar Fung, a theater director and playwright in Hong Kong.

Fung has just finished the first run of his latest piece of political theater, Case No. D7689. The title is a blatant insult toward Leung, in which D7 rhymes with an expletive in Cantonese that in English rhymes with “duck,” and 689 is Leung’s nickname (he famously won just 689 votes of 1,200 election committee members in the chief executive race in 2012).

Fung’s April show at the Ngau Chi Wan Civic Centre was set in 2026, when an imaginary trial of the chief executive will take place. “Leung manages to keep escalating the social and political tensions in the society,” Fung said. “Our protests are getting bigger and more violent. Even the silent members of the society are provoked to speak up and take part in rallies. This is sad, but he has certainly inspired more people to express themselves in creative ways.”

Or, as Charles Dickens put it: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

This former British colony has experienced some of the greatest political turmoil in its 150 years of history since Leung took office. We’ve gone from the 2012 record-breaking protests against a pro-communist national education curriculum, to the 2013 rally against the rejection of HKTV’s free TV license application, to the 2014 Umbrella Movement, to this year’s Lunar New Year violent clashes in Mongkok, aka the “Fishball Revolution,” and capped it all off with the latest airport luggage scandal.

Leung appears to have been doing his best to anger the public, but although he has been urged to step down on multiple occasions, he doesn’t appear to be going anywhere.

On the bright side, Hong Kong is enjoying a creative boom. A trove of artistic and creative works, in response to the city’s political turmoil amid greater influence from mainland China, have been produced in recent years. Traditional rallies chanting a few standard slogans no longer satisfy the needs of the furious people, and ordinary citizens are seeking innovative ways to express themselves every day. Political art has taken center stage in today’s Hong Kong—and Leung is the man we should thank.

“Leung has definitely given us a lot of inspiration,” said Kacey Wong, a visual artist who has been at the forefront of political art in the city.

One of his works, The Pinocchio (2013), a cardboard puppet that tells lies and wears a costume labelled “CY,” was exhibited during Hong Kong’s long-running January 1 anti-government protest. The puppet is wired to a recorder that plays a loop of Leung’s opposition for the chief executive spot, former chief secretary Henry Tang, attacking Leung during a public debate: “You lied. You are lying. How come you are always lying?”

What inspired Wong? Leung “does not have Hong Kong people’s best interest at heart. He is acting on behalf of Beijing only,” Wong said.

Leung is such an inspiration because mistakes committed by him and his government have been much more serious than his predecessors, his critics say. These range from his bungling of political debates, such as the one over universal suffrage of future chief executives, to the decision to go ahead with the construction of what many believe is an unnecessary express railway link between Hong Kong and the mainland. The project has an estimated cost of HK$85.3 billion (US$10.9 billion), almost enough to cover Stephen Hawking’s proposed space exploration project announced earlier this month.

Even Leung’s family drama garners public’s attention. His eldest, troubled daughter Leung Chai-yan often makes provocative statements in social media, and was seen slapping her mother twice in public during Hong Kong’s last Halloween festivities. This month the chief executive was accused of abusing his power to help his youngest, forgetful daughter Leung Chun-yan bypass airport security rules to bring on board luggage she had left outside.

Now not just artists but also the general public are producing creative works that have been going viral online.

This satirical cover version of David Bowie’s Space Oddity slamming Leung, for example, is sung by Steve James, a radio DJ with public broadcaster RTHK. It was one of the few satirical adaptations of pop songs sung in English.

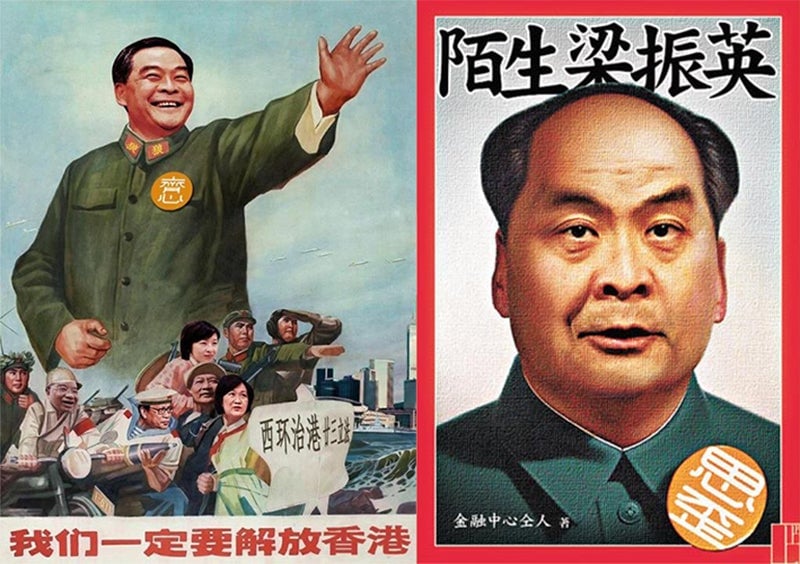

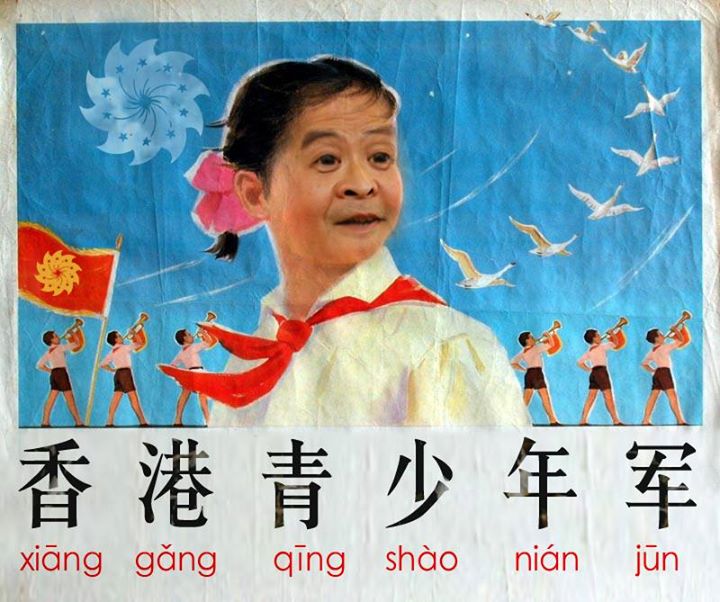

Other Hong Kongers have taken to mocking CY Leung for backing the Hong Kong Army Cadets Association, a pro-Beijing youth group he spearheaded, for which Leung’s wife Regina serves as “commander-in-chief.”

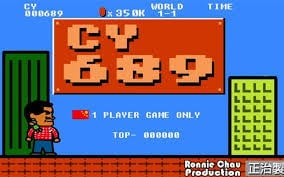

He has also been superimposed into video games:

And transformed into a wolf, for several reasons:

“There are more citizens who are not professional artists producing illustrations, altered images, and satirical covers of pop songs to express their discontent,” Fung said.

Wong argues that Hong Kong’s creative power reached a peak with the Umbrella Movement, caused by the Leung government’s rejection to the public’s demand for unscreened universal suffrage to elect of the city’s top leader.

The 79-day protests occupying the busiest districts of Admiralty, Causeway Bay, and Mongkok allowed the public to take their creativity and artistic power from the digital realm to reality, he said. Objects of disobedience were on display in public spaces, from installations built with umbrellas to sculptures of an “umbrella man” to the banner reading “I want genuine universal suffrage” nailed at the peak of the Lion Rock (a hill that looks like a crouching lion).

Wong called it a colorful exhibition, curated by the public.

Then, of course, there is the dystopian film Ten Years, which has garnered the city’s “Best Film” award and is headed to festivals in Singapore, Udine in Italy, and a crowdfunded screening in Melbourne, Australia.

“At least Hong Kong still has the freedom for people to express their opinion in this way,” Wong said.

Mathias Woo, artistic director of Hong Kong performing arts group Zuni Icosahedron, said Leung is unwittingly sending the city a wake-up call, asking citizens to decide our own fate now instead of letting others do the job, unlike 30 years ago when the Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed in 1984. “[Leung] is like a reality check for Hong Kong,” said Woo, a veteran in experimental and political theater best remembered for his recurring series East Wing West Wing.

“What Hong Kong faces now is the result of 18 years of poor governance. But Leung actually makes all of us in Hong Kong face the reality—we have to decide who we are and what Hong Kong can be,” he said.

Fung, 34, said he will continue his artistic journey. “I don’t think my works can inspire or even mobilize people to go to the frontline in social movements. But if I can create an artwork that can remind people of their passion and love for this city, they will stay and fight for our better future together,” he said.

Thanks in part to Leung’s unpopularity, ideas that were previously never discussed publicly, such as the cultural identity of Hong Kong and the city’s future beyond 2047—when the 50 unchanged years promised by one country, two systems agreement with the British expires—have been brought to the table. Localists championing for Hong Kong independence are earning greater popularity, as demonstrated in the recent Legislative Council by-election. A group of young pro-democracy politicians and scholars even published a joint declaration advocating for Hong Kong’s autonomy on April 21.

“Who would’ve thought about the independence of Hong Kong in the past?” said Wong. “Now people jokingly address CY Leung as the father of Hong Kong independence.”