Hong Kong’s next big development: a giant fake island where the last pink dolphins now swim

Hong Kong

Hong Kong

The Hong Kong government has big development plans for Lantau Island, the 147-square-kilometer landmass west of Hong Kong Island, in spite of fierce local opposition and a slowing economy.

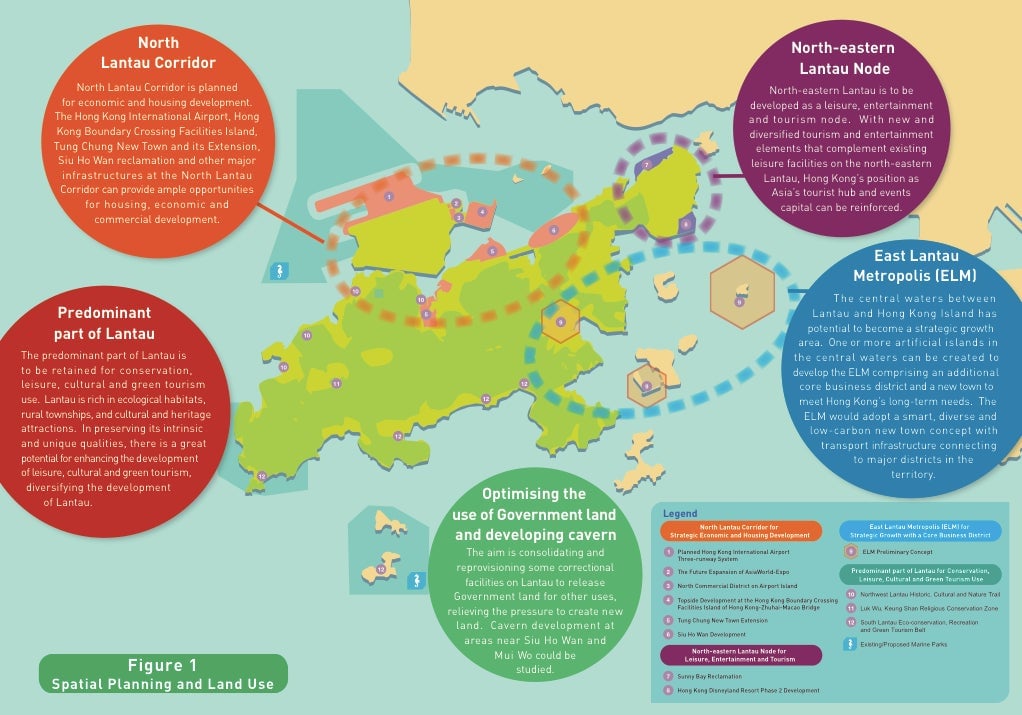

In a presentation made to various neighborhoods in recent months, the Lantau Development Advisory Committee spells out all that they wish to do to the area. It proposes to transform the sleepy island of fishing villages, beaches, wetlands, and the city’s largest country park into a new “kaleidoscopic recreation and tourism destination,” and a new shopping hub where visitors can “splurge and indulge.”

Public responses to the proposals are due tomorrow (April 30) via the committee website or fax, but a growing, vocal opposition is already squaring off against Hong Kong’s most powerful politicians—setting the stage for another clash between the city’s residents and leadership, which is increasingly viewed as out of touch with local citizens.

Lantau has a population of 105,000 currently. The outlandish development plans include a new East Lantau Metropolis that could house up to 1 million people, to be built mostly on reclaimed land, disrupting the habitat of the few pink dolphins that remain in the Pearl River delta in a way that many environmentalists fear would be fatal.

The development plans include:

- Create a “new town” on one or more artificial islands constructed in central Hong Kong harbor, and deeming it “low carbon.”

- Further reclamation to expand Hong Kong Disneyland, on Lantau, even as the park’s visitors fall.

- A railway corridor that links the city’s northern “New Territories” to western Hong Kong island via tunnels and railways.

The development plans come as Hong Kong’s population growth is slowing, real estate sales have fallen to SARS epidemic levels, and sales at the city’s existing malls are plummeting.

Developing this green area has always been controversial, and many harebrained proposals have been stopped through the years by public opposition, says Eddie Tse, who convened the Save Lantau Alliance.

“There have been various waves of government attempts at developing [the fishing village of] Tai O, which have been blocked since this is a very particular area with many stilt houses. And there are a lot of Sites of Special Scientific Interest on the island, not to mention the remaining pink dolphins. Some people in government accepted that the primary development measures had to be environmentally sound,” he said.

But this particular expansion may be hard to stop. The Lantau committee was formed in January 2014, after Hong Kong’s deeply unpopular chief executive, Leung Chun-ying, announced a plan to develop the island, part of a strategy of making Hong Kong “a bridge economy” to the mainland. In his 2016 policy address he supports the idea of a new metropolis built on an artificial island just off Lantau’s small town of Mui Wo, not far from Hong Kong Disneyland.

Of the 20 members of the Lantau committee, more than half are pro-development, allies of Leung, or part of the Beijing-leaning DAB party. It includes Peter Lam, the chairman of the tourism development board; Jack So, the head of the Board of the Airport Authority; and Algernon Yau, a Cathay Pacific Airlines executive, plus a number of pro-government politicians and a few academics.

Objection to the project is strong—dozens of green groups have signed a petition, and there have been marches and demonstrations. (During a previous round of consultations, in 2007, 80% of the public opposed any further development of the island.) But it is unclear what influence that will have. There is no public vote on the project—the government says it will create “a blueprint for Lantau development, which will set out the indicative implementation timetable for related projects” after the consultation period ends.

“It is very hard to see what can be done now,” says Tse. “The problem is, Lantau is so big, it is one of those ‘crimes without victims,’ because the plants, the birds and the animals are not victims that can voice their opposition,” says Tse: “Yet it is still a crime. And we would all lose Lantau.”

You can follow Ilaria on Twitter at @ilariamariasala.