Drop an ordinary lab mouse in tank of water and, unsurprisingly, the little guy will first panic, swimming furiously before simply giving up. Then infuse its gut with a certain kind of bacteria, and, just like that, the freaked-out little swimmer relaxes. Other research on mice suggests something similar: that gut bacteria can lower stress levels. The findings have tantalizing implications for helping chronically stressed humans.

So far, data on the interactions between probiotics, as the “good bacteria” are known, and people have been limited. However, a new study out of Japan provides new, if far from conclusive, evidence that certain gut bacteria can blunt our body’s response to stress.

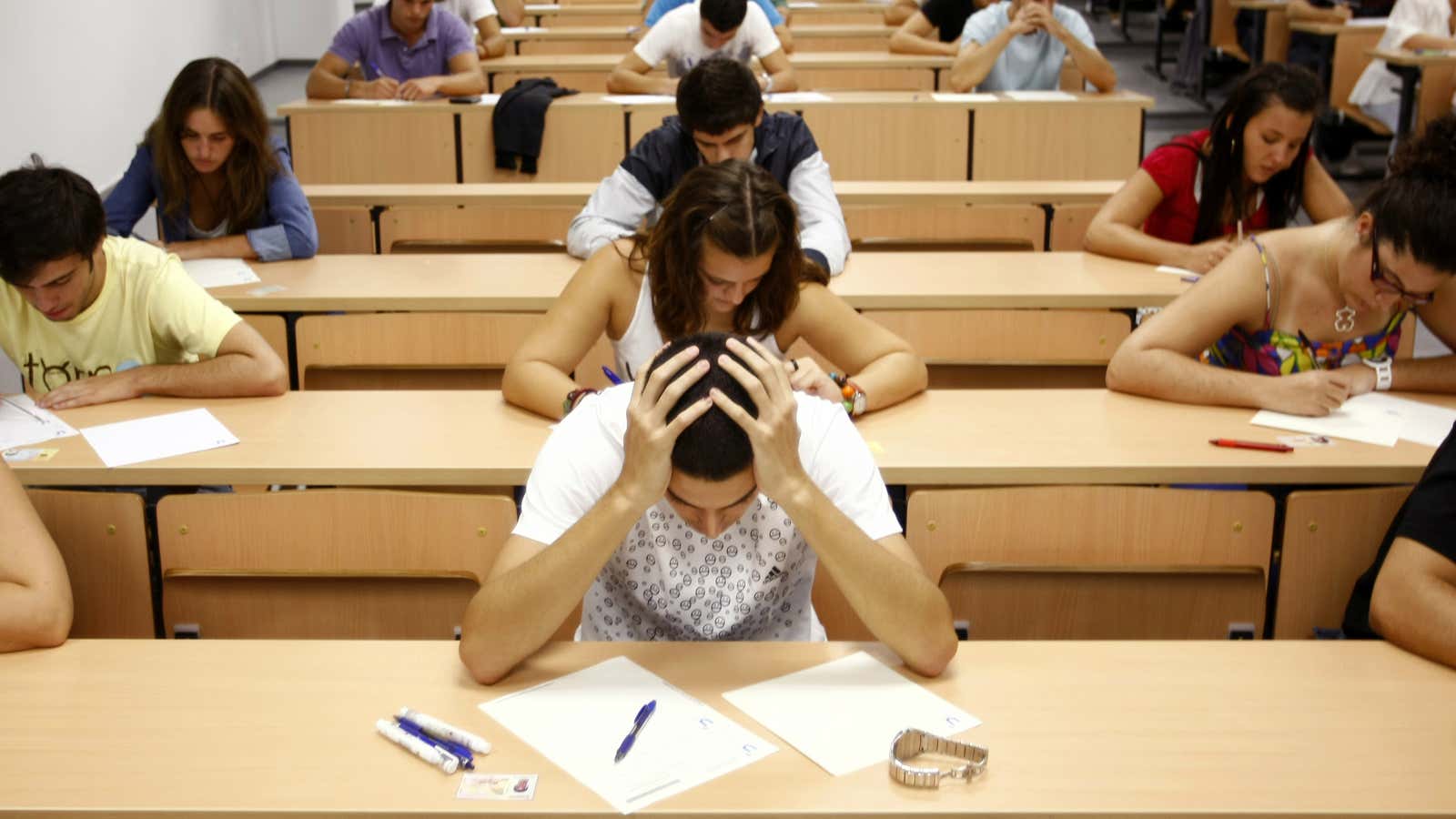

The study tested biological and behavioral stress indicators of 47 med students in Japan in the run-up to and after a major exam. It compared stress 23 of the subjects who began imbibing a probiotic drink eight weeks before the test with the 24 given placebo milk. The day before the exam, the placebo group’s levels of the stress hormone cortisol rose significantly. Those of the probiotics-drinkers didn’t. In addition, in the days before the exam, immune cells of those in the placebo group changed dramatically in response to stress, rising much less among students drinking probiotics. Those drinking probiotics also reported lower levels of stress and abdominal dysfunction compared with the placebo subjects.

Some pretty big caveats are in order here. First off, the sample size was tiny. Especially for the behavioral data, demonstrating clinical effects normally requires hundreds of patients, says Dr. Emeran Mayer, an expert on gut-brain interactions at the University of California, Los Angeles. Another cause for caution in reading too much into the results is that Yakult, the maker of a probiotic yogurt drink popular in Asia, sponsored the study; 14 out of the 17 coauthors work at Yakult.

That said, one of the study’s findings was particularly intriguing, says Mayer. Past research has linked acute and chronic stress with how immune cell behave. Other studies have shown the influence of probiotics on brain cells. However, this is the first human study to look at how probiotics affect the behavior of immune cells in response to stress.

“It’s remarkable when you think about it that a probiotic intake might have such a profound effect on the immune system,” says Dr. Mayer. “Hopefully other people will come out with similar reports with larger sample sizes that confirm these intriguing findings.”