Leer en español.

Omar Trinidad immigrated to the US from Mexico nine years ago and started working as a jornalero, as day laborers are known in Spanish, in New York City. Six years ago, he worked at a job site for a week, with the promise that he would be paid when the work was complete. But when Friday came, his employer disappeared.

“I felt bad because I didn’t know what to do,” he says. “I said, ‘Okay, how do I report this?’”

Wage theft happens to at least one out of five day laborers each month, according to Maria Figueroa, a professor at the Cornell University-School of Industrial and Labor Relations. Cal Soto, a coordinator at the National Day Laborer Organizing Network (NDLON), says each of the 45 workers’ centers affiliated with the group across the US reports at least 10 instances of wage theft each week.

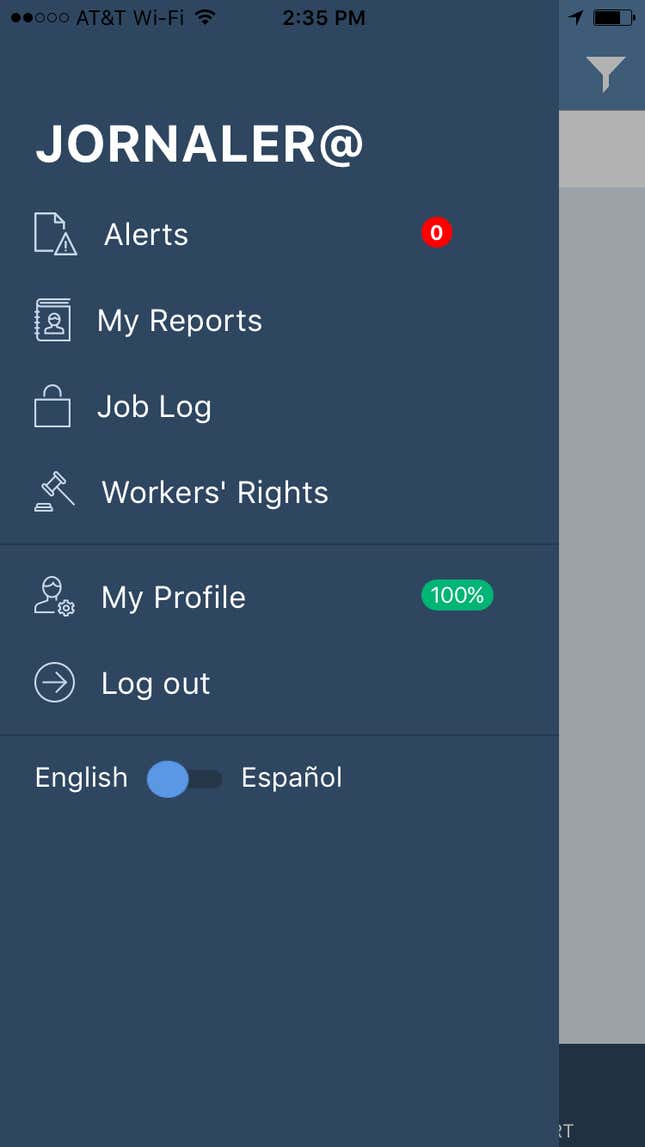

Today, Trinidad is helping create a tool that he hopes will reduce those numbers. He is working with Cornell, NDLON, and a New York City-based artist named Sol Aramendi to develop a mobile phone app called Jornalero.

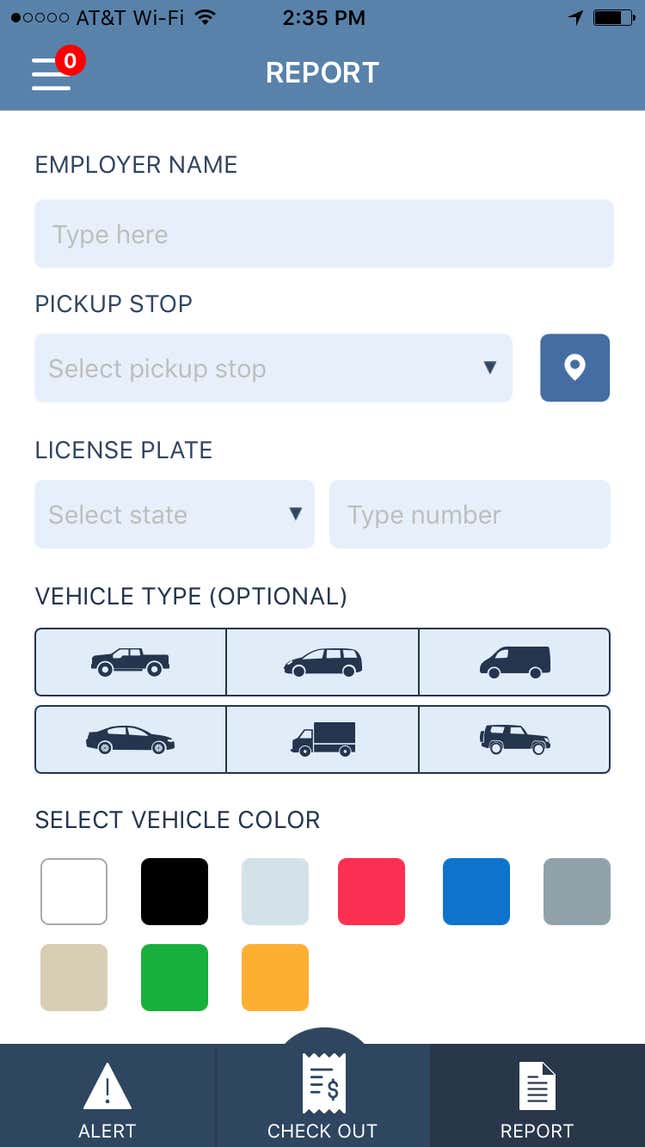

The Jornalero app has three main functions: First, it allows day laborers to record the hours they work. Second, it allows them to file a wage theft report directly to a workers’ center from their phone. Third, it allows them to send out an alert when they experience wage theft, to warn other day laborers with the app about nonpaying employers in the area.

Most day laborers have smartphones, according to Ligia Guallpa, executive director of the Worker’s Justice Project, a center in Brooklyn, New York. But one of the biggest impediments to fighting wage theft is the misconception among day laborers that they are not protected by US labor laws if they violate immigration law.

In fact, Guallpa points out, undocumented workers not only have the right to be paid for any work they complete, they also have the right to receive minimum wage, overtime pay, and worker’s compensation for injuries that happen on the job.

“There are a lot of misconceptions among the workers about whether their immigration status will matter if they stand up and fight back when they experience wage theft,” Guallpa says. “When they come in here, we can talk to them about how to fight back.”

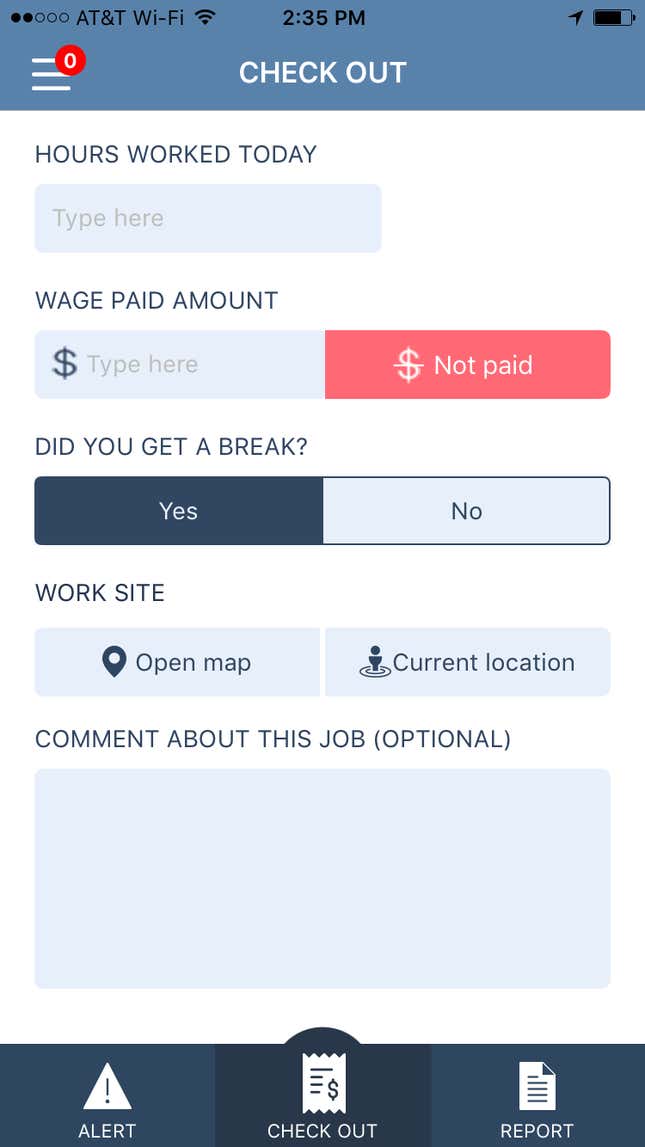

In court, winning a case against a nonpaying employer often comes down to a laborer’s ability to prove that they did the work, and many day laborers do not have much information to back their claims. “They don’t have the number of hours they worked, they don’t remember the date, or even who they worked for,” Figueroa says. “In that sense, it’s going to be a big step forward.”

The app will include a “check in” and “check out” feature that will allow day laborers to track the hours they work, where the work was done, and who they worked for. All the information collected in the app can serve as evidence to support day laborers’ cases in court, Figueroa says.

NDLON spearheaded the development of the app, with funding from the International Union of Painters and Allied Trades.

The organization hired a development firm called Rebel Idealist, which has done most of the technical work on the app, which has been developed for iOS.

A beta version of the app has been distributed to a small group of day laborers, according to Aramendi, and NDLON plans to release the app to the public later this year. The team hopes to make an Android version available soon as well.

NDLON centers throughout the United States will host informational sessions this summer where they will teach day laborers how to use the app and explain why it is important to spread the word and get more day laborers to participate.

Ultimately, the app is a tool, Guallpa says, but not a solution to the problem in itself. “Organizing is what really helps,” she says. “By making sure that all employers know we are connected, we are going to end wage theft.”