The real reason to be scared about Italy

The Cyprus banking debacle may be stirring up old fears about the spread of one small country’s financial crisis to the rest of the euro zone—but Italy’s finances could prove far more worrisome.

The Cyprus banking debacle may be stirring up old fears about the spread of one small country’s financial crisis to the rest of the euro zone—but Italy’s finances could prove far more worrisome.

Since February elections, Italian politicians have still failed to form a government and are unlikely to pass additional austerity measures, like the kind that would need to be imposed if the euro zone is to come to Italy’s aid. The Italian stock index—the FTSE MIB—has fallen 14% since late January, when concerns about the country’s political future began to intensify.

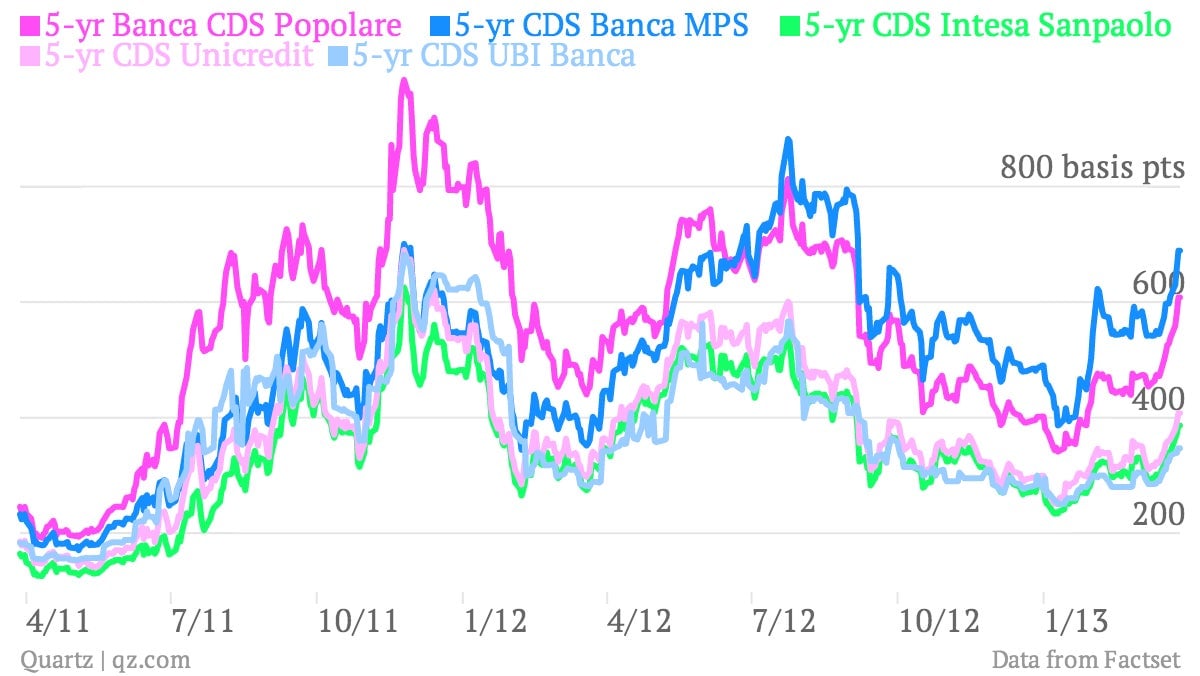

It may not be surprising, then, that the country’s financial sector is in bad shape. Particularly alarming are the prices of 5-year credit default swaps (CDS) on Italy’s major banks—essentially, insurance that pays out only if an entity defaults. The cost of these swaps has jumped higher during the last few weeks, but particularly since European leaders decided to impose cuts on depositors at Cyprus’s largest banks on March 16. Fears about Banca Popolare and Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena (commonly, Banca MPS) have been particularly acute.

This suggests two things:

- First, that the Cyprus bailout cast doubt on the European Central Bank’s (ECB) promise to “do whatever it takes” to save the euro. Confidence in Italian banks—and in European markets in general—grew in early July after ECB President Mario Draghi’s so-called “bumblebee” speech, which promised a backstop struggling economies. But this promise was never tested, and therefore may not be as good a deal as it seemed at the time.

- But contagion risk or political turmoil are not as important as fundamentals. Banca MPS and Banca Popolare appear to be in far worse straits than the rest of Italian banks, indicating that underlying fundamentals, rather than general distrust in the country’s banking sector, may be to blame.

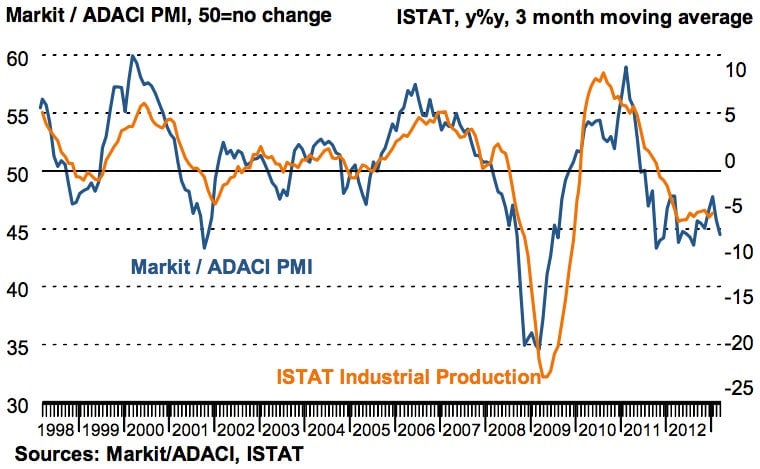

Meanwhile, Italy’s economic situation continues to worsen. And that has helped drive up the number of non-performing loans (NPLs). The number of NPLs on Banco Popolare’s book grew by 17.5% in 2012 (pdf), and those at Banca MPS grew 19.6% (pdf) in the same period. Total bad loans at Italian banks grew to €125 billion by the end of 2012, up 16.6% for the year. There is little to suggest this trend will turn around. In data released today, Markit found that Italy’s employment, manufacturing output, and new orders in March 2013 fell at the fastest rate in seven months (pdf).

(h/t @Real_Interloper)