Judging by China’s state-controlled media, you might not even be aware that today marks the 50th anniversary of the start of the Cultural Revolution. On May 16, 1966, Communist Party leader Mao Zedong launched a 10-year campaign in the name of combating capitalism. It is estimated that millions of people died from the political violence that swept across the country (or from suicide).

But whereas state media is keeping quiet about this sensitive period in Chinese history, two very different museums—and the state they’re in—speak volumes about the Cultural Revolution and how it’s viewed today. One museum honors and commemorates those who lost their lives, and is neglected and little visited. The other one is also trying to preserve history, but in a way that’s more palatable to today’s Communist Party—and is thriving.

The Cultural Revolution Museum in Shantou

On a recent spring day, a “Mr. Wong”—he declined to give his full name or profession—was one of the few people wandering amid the plaques and re-created tombstones at the Cultural Revolution Museum in Shantou. The museum is the only public memorial in China commemorating the victims who died or suffered grave harm from the atrocities of the decade-long period that began 50 years ago.

Wong said he had visited the museum numerous times. On this day, he brought along his 76-year-old father, who traveled from his hometown in Shanxi, over 1,000 miles away.

“We must remember history,” the elder Wong said of his first visit to the museum. “The younger generation doesn’t really care, while only a handful of older people would come here.”

In the lead-up to the 50th anniversary, the government banned activities or signs of remembrances of those traumatic years. At the Shantou museum, the exhibits were covered by the Chinese Communist Party’s propaganda banners and posters, starting earlier this month.

Located in the outskirts of Shantou, a southeastern port city in China, the museum opened with much fanfare in January 2005. Today, it is a very quiet place. At the entrance, the arch marked with “Cultural Revolution Museum” is draped with a banner reading “Socialist Core Values Promotional Activity.”

But there are signs of visitors who have refused to forget. Flowers, now withering under the sun, lay at the tombstones for the deceased. Shells of sunflower seeds litter the floor of Sian Tower, a stately structure at the center of the museum.

The museum was created by Peng Qian, the former deputy mayor of Shantou and a veteran member of the Communist Party. Born in 1932, he witnessed the Cultural Revolution first-hand. When he visited the pagoda park in Shantou’s Chenghai district in 1996, he was shocked to find over 70 little-known graves (including some mass graves) of those who were persecuted and died during the Cultural Revolution. He started planning a more proper memorial.

When the museum opened to the public in 2005, it received widespread media coverage. The opening ceremony was attended by luminaries such as Feng Jicai, vice president of the Federation of Literary and Art Circles. The many donors included Hong Kong tycoon Li Ka-shing, who sent inscriptions and 300,000 yuan.

After that, Peng held an annual memorial ceremony for those who died during the Cultural Revolution. The ceremonies stopped in 2014, a year after the museum’s bank account for receiving donations was closed, and some exhibits went missing.

About a year ago, Peng handed over the museum to the local government, citing his old age.

“I haven’t seen Peng for a long time. I can’t get in touch with him,” said Chen Zhaomin, one of the founders still in charge of the museum.

As the Wongs lingered among the artifacts, four boisterous young men nearby watched Hurry Up, Brother, a popular Chinese entertainment show, on an iPad. There were no attendants or other visitors in sight.

Repeated calls to Du Xuping, the director of the museum, were not answered.

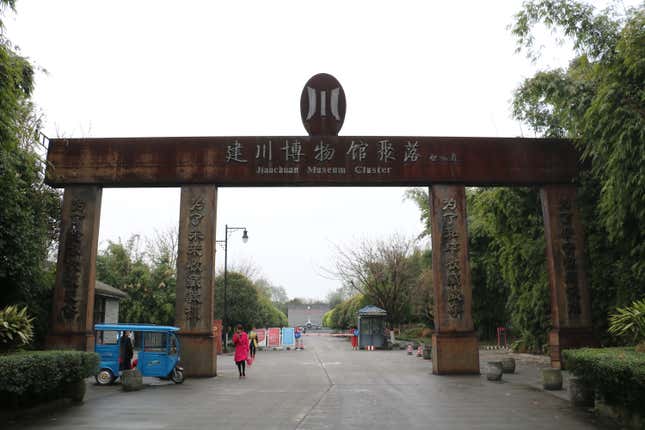

The Jianchuan Museum Cluster

Near Chengdu, the Jianchuan Museum Cluster also marks the Cultural Revolution. But compared to the Shantou memorial, it sticks to the government’s propaganda line and makes relatively few mentions of the period’s atrocities.

Also unlike its Shantou counterpart, it’s thriving. Consisting of six buildings and thousands of artifacts from the period, it receives over 100,000 visitors a month, according to its promotion office.

Opened in 2005, it’s the largest museum complex in mainland China, with 27 venues stretching across 1,500 acres of land.

Stacks of newspaper articles from the old days are on display in these museums. Washbasins and cups painted with quotations of Mao are exhibited behind glass showcases. Photos, propaganda posters, and stories of educated youths hang on the wall.

Another complex in the cluster is filled with thousands of badges engraved with portraits of Mao. Words like “loyal” and “long live Chairman Mao” fill the rooms. On one wall, four giant portraits of Mao, composed of red badges, look on.

In another building, hundreds of clocks painted with propaganda pictures and quotations of Mao (including “serve the people”) occupy the wall. The clock hands strike the hours in unison.

Established and funded by Fan Jianchuan, a 59-year-old Sichuanese property developer and collector, the museum is expanding, with new venues under construction.

The museums are divided into four themes: the Anti-Japanese War, the Cultural Revolution, major earthquakes, and folk culture. Over 100,000 Cultural Revolution exhibits show life under Mao’s rule.

The official museum website describes one set of the exhibits as reflecting “the glory of the mission, the devotion and effort of the youths, and the cohesive force and impetus they produced, which are important parts of the spiritual wealth of our nation.”

The publicity director of the museum cluster declined to talk about its exhibits on the Cultural Revolution. “This topic is relatively sensitive,” he said. “The museum cluster needs to continue to operate. If something went wrong, there will be a huge problem.”