“Let them get sleep!” Similar to the way Marie Antoinette’s infamous—and not entirely accurate—phrase about a certain dessert has come to represent classist ignorance, the West’s newfound fascination with sleep is the latest example of extreme cognitive dissonance.

A 2013 Gallup poll reported that 40% of Americans are not getting the recommended seven to nine hours of sleep per night. Eager capitalists have quickly recognized this hole, swooping in with new products and new slogans and new ironies. Today, we’re being sold everything from digital gadgets to celebrity-endorsed mattresses to help us sleep better and longer. Bizarre attempts to commodify a basic and essentially free human necessity only serve to highlight how troubled our lives have become.

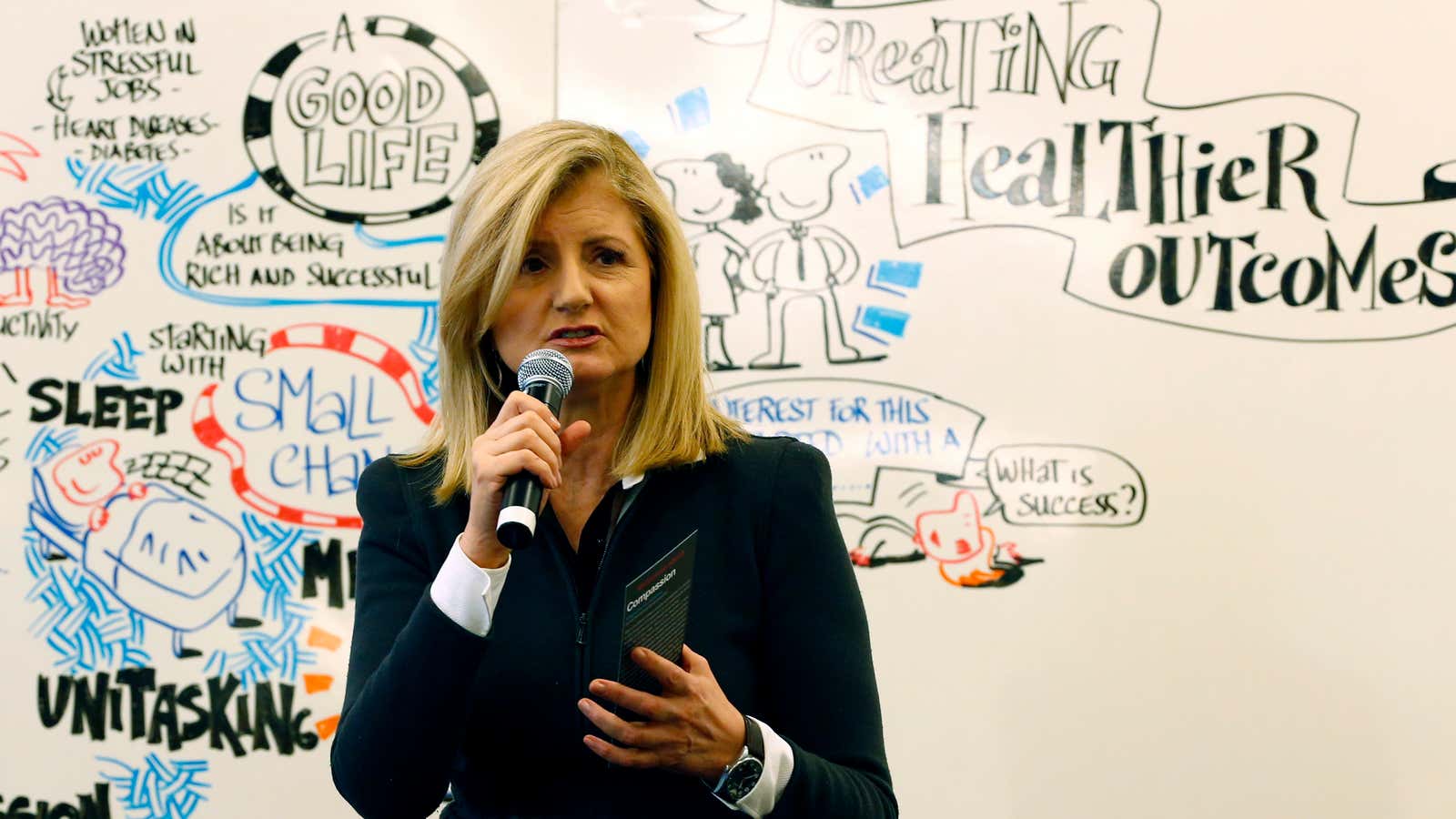

For the past month, for example, media mogul Arianna Huffington has been aggressively peddling her new book, The Sleep Revolution. A successful capitalist, Huffington has been praised and criticized in equal measure for the labor practices that built her massive online empire. Now, the media mogul turned lifestyle guru is hoping to sell us something that is free under the guise of luxury.

In The Sleep Revolution, Huffington observes we are collectively experiencing a global “sleep crisis,” abetted, no doubt, by the extant digital culture which demands that we be plugged in 24/7. Oddly, she suggests this crisis is tied to an individual desire to make money, rather than the interests of employers attempting to maximize the efforts of their employees. In an interview with ThinkProgress, she went a step further, blaming a masculine workplace culture that believes bragging about a lack of sleep indicates dedication: “I think it starts with men using it as a symbol of virility almost. But then a lot of women who think it’s how to get ahead in the workplace have adopted it. It seems primarily a machismo thing, like whose is bigger?”

No one is arguing against the need for sleep. But it’s an observation that rings hollow for many, especially those who lie awake at night worrying about job insecurity or how they are going to cover their next rent check. There are so many causes for sleep deprivation that Huffington’s recommended “Sleep Revolution products”—like KIND granola or a $30 SoulCycle class—are unlikely to remedy. Not to mention the obvious fact that these “first world” remedies are tokens of a particularly insidious brand of privilege. (A sugary granola bar will not help you sleep. Neither will lip balm.)

In this new and increasingly unstable society, many of us work so hard and for so long not because of some type of machismo, but because the current economic climate dictates that we do. In the growing freelance economy especially, an environment replete with “at will” contracts,” we represent the underpaid and the undervalued. Project Time Off states that three quarters of Americans are stressed at work. Their 2014 study found that “one third (33%) of employees say they cannot afford to use their time off and nearly a quarter (22%) of workers say that they do not want to be seen as replaceable. Roughly three-in-ten (28%) employees do not use all their time off because they believe it will show greater dedication to their company and their job.” Freelancers may not have an office to go to, but that doesn’t mean we are always—or ever—on vacation.

The driving motive to work ourselves to death at the expense of our health is not ego—it’s anxiety.

To Huffington’s credit, she seems to at least be aware of this problem, citing a 2013 study from the University of Chicago that concludes socioeconomic status has myriad effects on the quality and quantity of sleep. “Lower socioeconomic position was associated with poorer subjective sleep quality, increased sleepiness and/or increased sleep complaints,” she noted, speaking with Maclean’s magazine in April.

With stagnant wages that reflect America’s larger stagnation pertaining to social mobility, it is no wonder that the US Centers for Disease Control stated last year that “insufficient sleep is a public health problem.” And the National Sleep Foundation’s inaugural Sleep Health Index, published in Dec. 2014, reported that “45% of Americans say that poor or insufficient sleep affected their daily activities at least once in the past seven days.” The NSF indicated that quality—not quantity—of sleep was the primary issue affecting Americans.

Myriad studies have enumerated how sleep is negatively affected—both in quantity and in quality—by a variety of environmental and psychological stressors specifically experienced by people of lower socioeconomic status. Researchers Cassandra Okenchukwu and Orfeu M. Buxton of Harvard University found a host of environmental factors that affect sleep. “An example is poor sleep quality due to stress in a rodent-infested apartment, or keeping the windows closed and locked in a non-air-conditioned bedroom for safety worries,” they explained in a piece about how poverty affects sleep. Within the scope of American demographics in accordance with a 2009 study and a second 2010 study, this means that women, black Americans, and Hispanic Americans have the most compromised sleep.

In addition to environmental factors, a host of psychological stressors contribute to sleep deprivation. Unfortunately, sleep deprivation and poverty are cyclically connected: “People who sleep less earn less,” Megan Werft wrote last year in a piece for Global Citizen. “In fact, one study found that one more hour of sleep per night can increase wages lead to a 16% higher salary annually in the US (about $6,000).”

In a depressing example of capitalism’s flaws, society remains more than happy to capitalize on our suffering, marketing newfangled products to help us bridge the chasm between sleepless and sleep-full nights. The fact that so many cannot afford these products is explained by a classist (and therefore racist) assumption that people of lower socioeconomic status simply do not care or want to sleep better. It’s similar to the “pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps” assumption that those living near the poverty line do not want to succeed or do not want to take care of their bodies and those of their children. As a result, anyone who cannot begin our daily “journey” to dreamland at 10 pm are infantilized by the very system that disables us.