Patients are actively looking to engage their physicians online, but doctors aren’t too keen on the idea. What’s the big fuss?

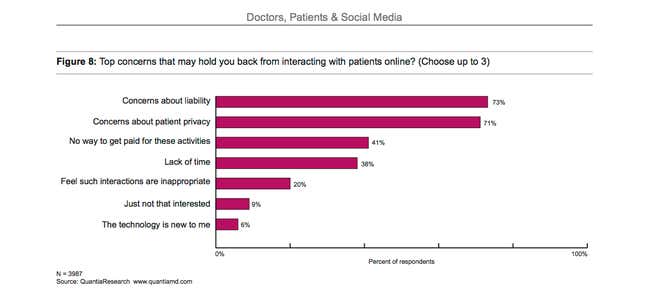

Fears of potential lawsuits and concerns with patient privacy are a big part of what’s holding doctors back from starting their own Twitter handles, but Kevin Pho (he’s a real doctor and a social media doctor) thinks physicians must embrace social media, albeit smartly. He concedes it can “blur the line between a professional doctor-patient relationship and one that brims on being too personal.”

But for doctors to stay sidelined is hardly the right tactic. Pho says the reality is that “an increasing number of patients get health information on Facebook, so it’s important for physicians to have a presence there.” Does that mean doctors must let patients in on their vacation photos and updates on what they ate for dinner? No, instead Pho advises they keep a professional Facebook page.

Of course, chat rooms, clinician review sites and physicians on Facebook won’t solve international health care shortcomings (certainly not the American health care system’s, anyway), but if patients are eager to interact with their doctors on the internet, doctors need to meet them halfway; 59% of US adults have looked online for health information in the past year.

Pho’s own blog, KevinMD.com, has amassed a steady readership of folks looking for quick medical advice and expert insights into breaking medical news. His latest book, co-authored with Susan Gray and titled “Establishing, Managing and Protecting Your Online Reputation: A Social Media Guide for Physicians and Medical Practices,” encourages physicians to follow his lead.

Quartz caught up with Pho to get more specific on how the doctor-patient relationship might evolve on social media. Edited excerpts:

Quartz: A lot of patients want to vet doctors online before seeing them in person. Which sites, if any, are best to evaluate doctors’ performance, blending both patient reviews with outcomes?

Pho: More patients want to research their doctors or hospitals on the web prior to visiting them. According to Pew Internet, 44% of online patients look for such information on the web. The problem is that few viable sites exist that blend both narrative reviews and patient outcomes.

There are dozens of online physician rating sites, such as Vitals, Healthgrades and RateMDs. But according to a recent study, most doctors on these sites average between two and three ratings. Hardly enough to make an informed opinion.

In Massachusetts, Consumer Reports gathered feedback from over 60,000 surveys and rated close to 500 primary care groups in the state. Physician rating sites need that kind of robust data in order to have any usefulness for patients.

Macarthur OB/GYN is a great example of how physicians can use Facebook.

Q: Has social media changed doctors’ waiting room times? If not, will it?

Pho: The number of physicians who use social media professionally is still relatively low. However, social media can increase the transparency between doctors and patients. For instance, there are emergency departments that post wait times on Twitter. And practices can post on social media if they are running behind, giving scheduled patients a heads up that their appointment may be delayed. It’s up to hospitals and physicians whether they want to harness that potential.

Q: Privacy seems to be a big concern among physicians. Should doctors be friends with patients on Facebook?

Pho: The short answer is no. There is information on personal Facebook profiles that physicians may not necessarily want their patients to know about—pictures of their children, what they did on vacation, what they do after hours. Allowing patients access to a personal physician’s profile has the potential to blur the line between a professional doctor-patient relationship and one that brims on being too personal.

Instead, I advocate a “dual citizenship” method that separates a personal and professional online identity. It’s an approach that professional medical societies endorse, such as the Federation of State Medical Boards. Physicians can still maintain their personal profile on Facebook, but restrict access to it to close friends and family members.

Then they should have a separate Facebook Page for their practice that is open to the public. Doctors should maintain a professional demeanor on this page, and use it to connect with patients, share stories about the practice, and guide the public to reputable health information on the web. An increasing number of patients get health information on Facebook, so it’s important for physicians to have a presence there. A professional Facebook page is an ideal way to do so.

Quartz: Considering how quickly we’re advancing, is it unreasonable to think that a majority of patients will soon be sending photos of ailments and video chatting with their doctors?

Pho: No, that’s already happening in some clinics today. Pediatrician Natasha Burgert in Kansas City uses text messages to stay in touch with her teen patients. And some insurers are embracing telemedicine and using video conference tools where doctors can “see” patients online, for simple urgent care issues.

The biggest barrier preventing doctors from using more of these virtual tools is the current payment system, which essentially pays doctors only for a face to face office visit. Health reform proposes to change this payment system, which, in part, can encourage more physicians to communicate with patients via email or over a web chat.