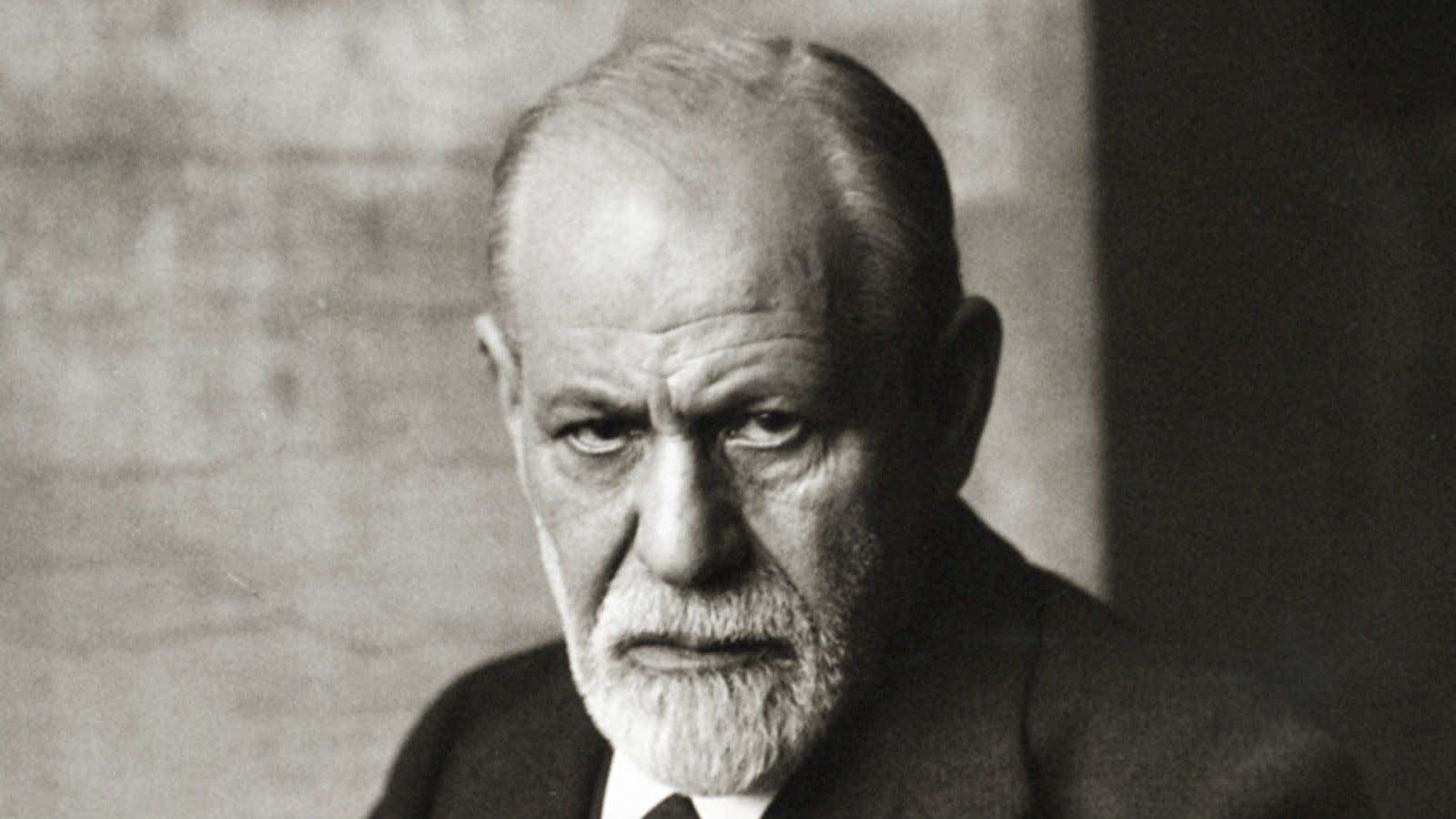

The psychoanalysts’ couch is often seen as the path to inner truths, revealing long-suppressed insights about how you secretly want to have sex with your mother and view every authority figure as a manifestation of your father. But are the personal narratives developed in therapy really, objectively, true?

A recent publication of The Psychoanalytic Quarterly explores this question of whether truth is relevant, with many psychoanalysts arguing that “truth” is besides the point to breakthroughs in therapy.

Although psychoanalysis aims to uncover the “true” self, its methods rely heavily on personal memory and subjective experience, neither of which are accurate objective measures of reality.

In the editor’s introduction to The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, Jay Greenberg writes that Freud himself recognized this paradox. He points to acknowledgement in Freud’s 1899 paper “Screen Memories” that “memory is a composite, created from bits and pieces of what “actually” happened and reshaped by the needs, anxieties and defenses active at the time of their recall.”

But Fred Busch, training analyst at Boston psychoanalytic institute, argues that this is not a drawback to the psychoanalytic process.

“The way I work and many of my colleagues is we’re more interested in building a representation of how the person thinks about what’s going on, rather than trying to find out what’s actually going on,” he says.

So while memories may be an unreliable representation of reality, they do show how someone perceives the world. We all create fantasies and theories as to why we behave in certain ways but the prism through which we perceive others is important in psychoanalysis, rather than the actual behavior of others.

For example, Busch says that a child whose mother struggled with breastfeeding might have anger as a result of not having their needs met. But instead of accepting their own anger, they might come to view their mother as an angry person.

Psychoanalysts, says Busch, are particularly interested in perspectives such as this that cause personal difficulties. With the help of therapy, patients can develop a more nuanced theory about their behavior and those around them, which gives them the chance to perceive the world and themselves differently. “It changes the inevitability of action to the possibility of reflection, which gives a person more freedom in how they react in areas where they’re having difficulty,” he adds.

And so, rather than focusing on reality, a psychoanalyst can explore a patient’s perspective of the world to challenge any theories that cause personal difficulties. In this way, a patient would have greater freedom to behave and think differently and so, in sense, have more truthful access to their own mind.

Meanwhile Liz Allison, director of the psychoanalysis unit at University College London, argues that it’s the experience of discovering what feels like a truth about oneself, and doing so in the presence of another person, that makes psychoanalysis so valuable.

“Out sense of selves develops through our relationship with others,” she says. “That development of trust in a therapeutic situation is a foundation for what can happen beyond it.”

She believes that the feeling of being known by another person can make a patient far more open to new experiences and learning.

However, while the truth is not necessary, that doesn’t mean that it’s irrelevant to therapy. What if, for example, someone has a fanatical belief that they’re the rightful heir to the Swedish throne—is this belief valuable if it feels true? Allison says that delusions can be experienced to a greater or lesser degree by anyone, but are distinct personal “truths”. In delusions, any sense that a worldview is a representation of the world is lost, and instead there’s a sense that a worldview is the world. These are indeed distinct from, and far less healthy than, personal insights from psychoanalysis.

But overall, it seems that uncovering factual truths is not the end point of psychoanalysis.

“When one goes into a therapeutic relationship it’s not really about discovering fact, or determining the historical truth about what might have happened in early childhood,” says Allison. “Knowing that or not is not in itself going to be helpful.”