Half a century ago, the United States was at war with Vietnam. And it wasn’t a war of existential necessity (for Washington), but a war of ideology—intended to snuff out the tide of communism flowing into Southeast Asia. Though the current conflict with the Islamic State stems out of broader competition for oil resources in the Middle East, it too is rooted in a battle of ideologies between East and West.

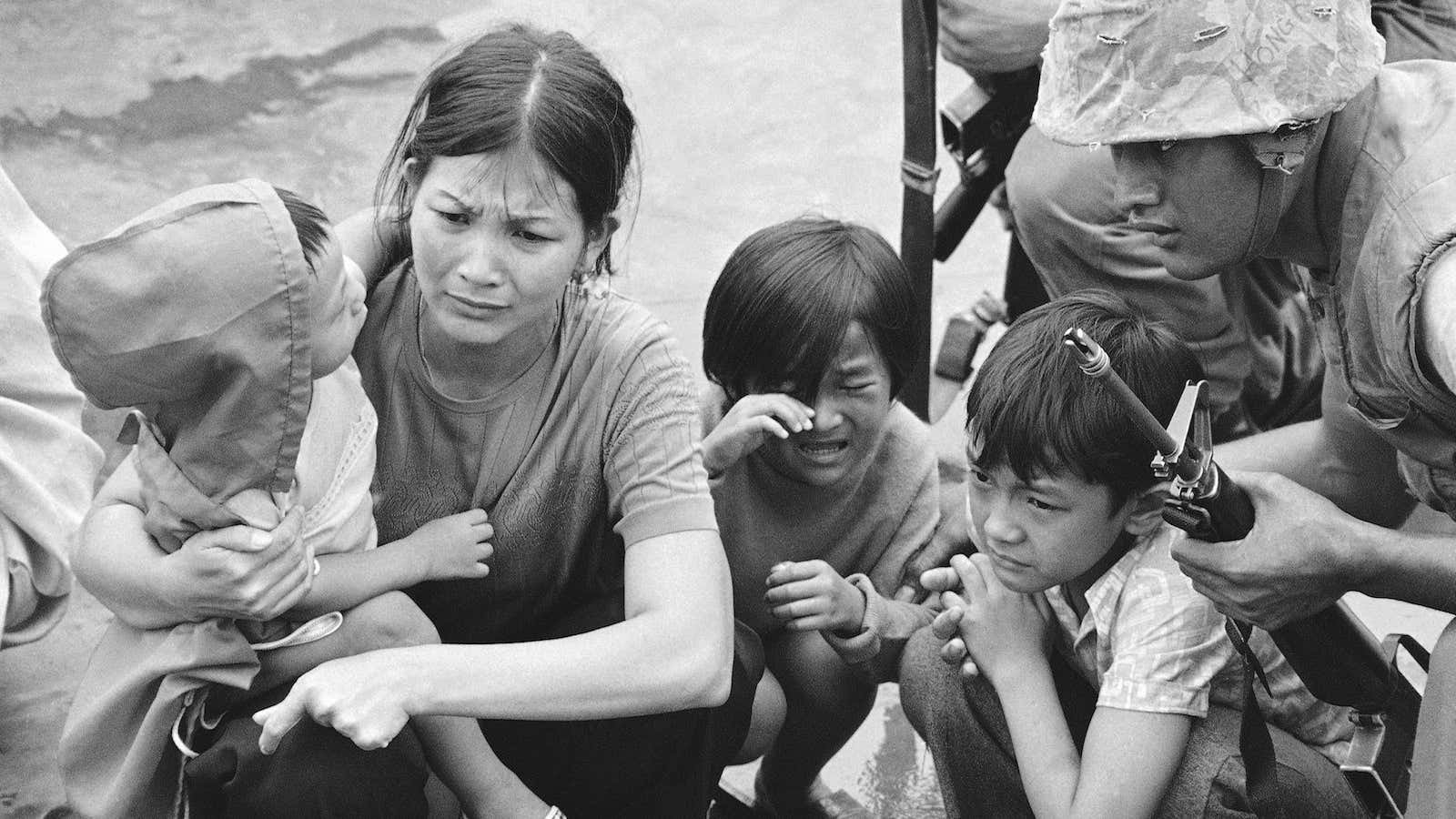

The Vietnam War was an equally bloody affair, with thousands of lives lost on both sides. The actions of the United States military—the deployment of Agent Orange, the firebombing of Vietnamese women and children—left a country simmering in resentment of Washington for decades.

Today, the American president is touring that very same country on what could be described as a palpably friendly state visit. The United States is Vietnam’s top export destination. Vietnam numbers among the ten most common countries of origin for immigrants coming to the United States, and the established Vietnamese-American community enjoys economic mobility and entrepreneurial success.

The latter is perhaps partially attributable to a law signed by president Gerald Ford in 1975, the year US forces withdrew from Vietnam. The Indochina Migration and Refugee Act granted political migrants from Vietnam and surrounding countries special status to enter the United States and established a resettlement program. It brought roughly 130,000 Vietnamese, “generally high-skilled and well-educated,” according to the Immigration Policy Center, primarily to the states of California and Texas.

At the time, it was not a popular move. Post-war resentment stewed west of the Pacific as well—only 36% of Americans favored Vietnamese immigration.

But since arriving, the Vietnamese have largely devoted themselves wholeheartedly to the national project. According to Pew, Vietnamese Americans are generally “upbeat and optimistic” about their community’s future in America. Eighty-three percent believe that “most people can get ahead if they work hard.”

Given the parallels between US involvement in Vietnam in the 1970s and the current conflict with ISIL in Syria, one has to wonder why a refugee resettlement program on the scale of the Indochina act has yet to be created for Syrian refugees. Since the outbreak of fighting in the region, Washington has agreed to take only 10,000 migrants out of the more than four million Syrian refugees registered with the United Nations. And reports from as recently as April 2016 says the US is “way behind” in reaching that goal.

Some cite fears of jihadists hiding among well-meaning refugees as justification for accepting fewer Syrians, if not none at all. This notion, of course, overlooks the strenuousness and complexity of the asylum review and refugee screening process in the United States. And it neglects to consider precedent—how many European refugees committed acts of violence against Americans in the wake of World War II? How many Vietnamese in the 1970s and ’80s?

One hundred and thirty thousand Vietnamese refugees established a sound foundation for what would become one of America’s most vibrant and contributive ethnic communities. Syrians, a highly educated people, could almost certainly do the same, if only afforded the opportunity.