A bright flash, followed by hell on Earth. That’s how many survivors describe the moment a United States pilot dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Chen-Lin Tsai is no different. “I thought this is it,” he tells me. “This is the end. It’s over.”

Thankfully, my grandfather’s life didn’t end that day in Japan. But one little kilogram of uranium took so much from that 19-year-old, and so many others. And it will never be given back.

US president Barack Obama will be the first American president to visit Hiroshima when he arrives today (May 27). The White House has made it clear that Obama will not apologize on behalf of the US for dropping the bomb. But for those who experienced the first use of a nuclear weapon against enemy forces, the fact that Obama plans to acknowledge the tragedy at all does count for something.

The Americans nicknamed the bomb dropped on Hiroshima “Little Boy.” Chen-Lin Tsai was once a little boy, too. He was born in 1926, during the height of the Japanese colonial period in Taiwan. Growing up in a small fishing village, he experienced firsthand the vigorous implementation of the “Japanese Movement.” Taiwanese locals were forced to speak Japanese, wear traditional Japanese garb, and change their surnames. Some were even drafted to fight in the Japanese army.

But no amount of indoctrination could fool Chen-Lin into thinking that Taiwanese weren’t second-class citizens in their own homeland. He viewed education as the one opportunity to change his destiny. Wanting to become a doctor, he knew that his best chance for advancement lay across the East China Sea. And so, in 1942 at the age of 16, he packed a single suitcase and some borrowed money and boarded a ship to Japan.

Three years later, as the war drew towards a resolution and as Allies pushed them back, Japan mobilized college students throughout the country to help with wartime manufacturing. Chen-Lin accepted that, for the time being, his dream of becoming a doctor would be put on hold.

It was an inconvenience, but up until this point, he had no reason to fear for his life. “US forces have not dropped any bombs in residential areas, the public had no fear of warplanes, and nobody had needed refuge in any bomb shelters. Just school and work, as usual,” he said.

That all changed on the morning of Aug. 6, 1945. “It was a beautiful morning with a clear blue sky. On my way to work, there were several aircraft in the sky. Air raid sirens went off several times, but nobody really thought it was a big deal.” He strolled into the factory around 7 am and got to work.

The flash transcended broad daylight. The boom eclipsed the sound of factory work. Light bulbs exploded and windows shattered. As the roof and walls came down on top of Chen-Lin, the astounding light gave way to darkness. But when he finally extricated himself from the rubble, he saw only red.

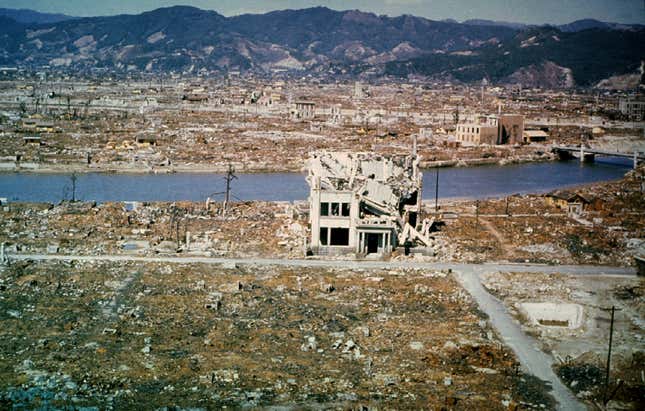

Hiroshima was on fire.

“I have to run, or I’m going to die,” was all Chen-Lin remembers thinking in that moment. The pile of wood where his factory had once stood was nearly six kilometers from the explosion’s hypocenter, giving him a clear view of the full scope of the devastation.

The sky had turned dusty, and all of downtown was engulfed in flames,” he told me. “From just one flash of light. How could this be? What is going on?”

“Remembering what the government’s emergency instructions, he took off running towards the city’s southern port. The horrors he witnessed on the way have haunted him ever since.

“Everyone was running,” he said. “There were so many injured, but the wounds were so different from what we learned in wartime education. Most of these victims didn’t have visible fractures. No large lacerations. But their skin… it was like peeled steamed sweet potato. I don’t know how else to describe it. Some on the face, chest, back, legs … their skin was just falling apart and the whole time, they were wailing and screaming.”

Chen-Lin vividly recalled running past a girls’ school and seeing hundreds of students huddled on the ground, crying. Most of them had horrible burns on their exposed lower legs. They had been outside on the playground, in full view of the blast.

As Chen-Lin neared the port, medical emergency personnel began to arrive in the area. He recorded in his diary: “They put medicine on the wounded, but told us not to give them any water, that they would die if they consumed water. But these people were suffering, screaming out at us ‘Please, I need water! PLEASE!’ I didn’t know what to do.”

A few days later, many who had survived the initial explosion began to die without warning. A mysterious disease was causing purple abscesses, vomiting, hair loss, and nosebleeds. Chen-Lin and most of the public were unfamiliar with what the doctors were calling acute radiation syndrome. All he knew was that most of the people he had escaped to the port with were dying.

Three days later, the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

Chen-Lin was eventually able to secure a seat for himself on a boat traveling back to Taiwan. The Japanese government, as part of a post-war agreement, had provided funds for Taiwanese students to return to their homeland. Sitting next to him were two urns, all that remained of two dear childhood friends who had been less fortunate that August morning.

The road home was not an easy one. While waiting for the Japanese to provide money for transport, he was forced to take part-time jobs at the Yokohama port to survive. He remembers the transition of Yokohama into a US naval base as American occupiers arrived in the months after the bomb. “You could see poor Japanese children begging for bread, canned food, or candy from American soldiers,” he said.“I couldn’t help but sigh, thinking that now was the time Japan would suffer from their defeat.”

When he had first arrived in Japan, Chen-Lin said he was constantly reminded by other foreign students not to speak his mother tongue in public. “Only if you wanted to be mocked and treated as a second-class citizen, or ‘Chinaman.’”After the war, those same people would congregate and speak their native languages proudly, brandishing national flags and acting like conquerors. On public transportation, he found “Victorious Nation Only ” train cars,with Japanese forced to squeeze into smaller cars.

Sometimes, when the trains were overcrowded, he’d hear shouts of “Get the Japanese off!” followed by raucous laughter from fellow foreigners.

Sixty years later, the Japanese government allowed overseas foreign “Hibakusha” (nuclear bomb survivors) to seek compensation. Each survivor qualified for a 33,000 yen payment ($300) each month, paid out by the Japanese government. As of 2012, over 200,000 people hold this certificate. The volunteer lawyers from Japan came to my grandfather, but he never felt comfortable applying.

It is all too easy for those of us one or two generations removed from the realities of World War II to politicize and pontificate on issues like whether or not president Obama should apologize during his visit to Hiroshima. But when consulted directly about the matter, my grandfather’s thoughts were quite clear.

“Peace is what’s most important,” my grandfather told me. “There are no winners or losers. During the war, everyone lost.”

I felt ignorant even having asked the question. As we debate the necessity and minutiae of Obama’s visit, survivors like Chen-Lin know we can’t see the forest for the trees.

Obama’s trip is not about apologizing. It’s not about an admission of guilt. It’s about admitting the significance of what happened there. It’s about remembering those who were affected. It is about making a commitment to work towards a better world.

As J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the A-bomb, pointed out, our scientific pursuits have given us the capacity to quite literally end worlds. Japanese schoolchildren, Taiwanese, and Korean students, and American prisoners of war all died that day. “Little Boy” did not discriminate.

US assistant secretary of state Daniel Russel said of his own trip to Hiroshima: “It’s a powerful experience. It’s a sobering experience. It’s a humbling experience … It reminds us of the indisputable truth that war must be a last resort, that it’s the deep obligation of every person in a position of responsibility to work for peace, and there’s no person with a greater responsibility than President Obama.”

Chen-Lin Tsai would agree.