“This is good news in the fight against cancer.” That’s what US vice president Joe Biden said as 2 petabytes of genomic and clinical data were released to the public last week. The trove features 440,000 DVDs worth of information—including full genome sequences—from 12,000 patients, raw and unprocessed.

How will it help improve cancer treatment?

Cancer is not one disease

Cancer is an umbrella term for a number of diseases which cause cells to grow uncontrollably following mutations in their DNA. We classify the type of cancer based on where the disease appears—in the kidney or lung, say—but the precise mutations that cause it differ from person to person.

Scientists hope that by profiling tumors—recording in detail the genetic sequence, structure, and differences from healthy cells—they will reveal clues about how to stop them. And the more people they can collect data from, the better.

Cancer scientists have a handle on the cancer mutations that occur in at least 2% of the population. We’ve learned, however, that there are many many important mutations that only occur in less than 2% of the population. It’s hard to detect and examine those without very large datasets covering a comprehensive range of cancer patients.

As genetic sequencing has become cheaper and easier, that data now exists. However, it is spread over many databases, each with its own quirks, making it difficult to do any useful analysis across the whole range.

The power of data

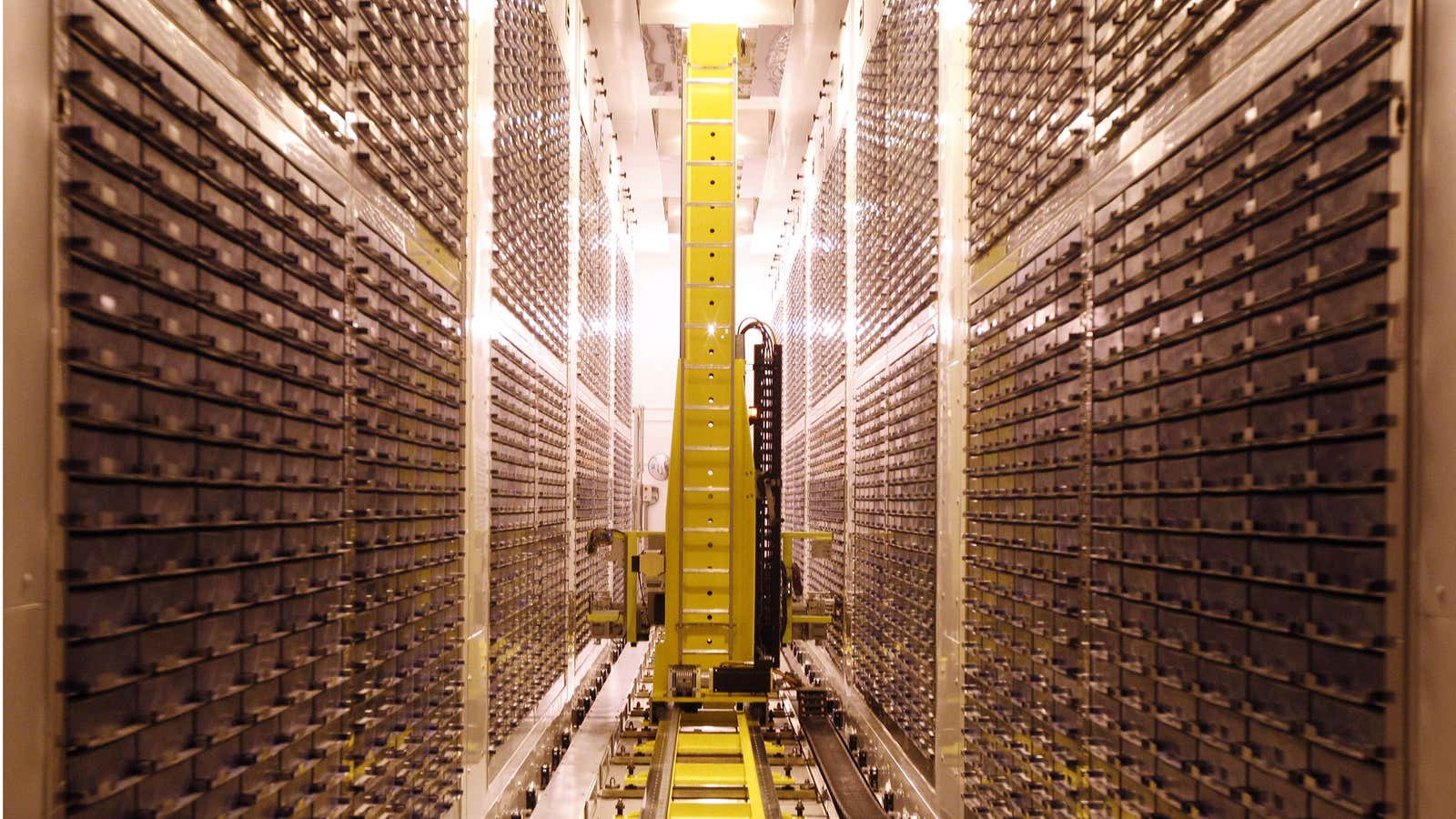

That is the problem that the US National Cancer Institute’s Genomic Data Commons (GDC) hopes to solve by bringing together the two largest existing cancer datasets—The Cancer Genome Atlas and TARGET. It has also issued an open call for scientists to submit data to make it an even bigger resource for researchers.

Cancer scientists can understand different tumors better if they have easy access to a huge, unified database they can query with questions and get meaningful, reliable answers. If someone wanted to study kidney cancer, for example, the GDC has profiled 1,700 types of kidney tumors. Its power comes from bringing all that information together in one place and smooth it out with algorithms, according to Simon Forbes, a cancer scientist at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

This is another step on the road to personalized medicine—treatments tailored to individuals based on the specifics of their body, genetics, and the disease in question. With this information, a doctor might know exactly which unique combination of drugs and chemotherapy, would best target a patient’s cancer, which could be different from another person with the same symptoms. With more than 200 types of known cancer, linked to a wide variety of causes, such precision is needed.