When I first meet Josh Wooten at a deli in Gainesville, Florida, he flashes a big smile at me, squinching up his eyes. He looks like any other hopeful young man making the transition to college, from his faded graphic t-shirt to his scuffed tennis shoes. But he is seated next to a large, black walker.

“Friedreich’s Ataxia is like being drunk all the time except without the fun,” says Josh, who is 19 years old. “You are tired all the time and constantly feel off balance.”

FA affects roughly one in every 50,000 people in the US. But there are hundreds of millions more around the world with rare degenerative illnesses that affect the nervous system like Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, Lou Gehrig’s disease, and Pompe disease.

Everyone who suffers from these diseases hopes for a cure. But in the meantime, each individual must grapple with the question of how to go about everyday life with the knowledge that medical progress is racing against the clock.

Two years ago, Josh became patient zero in an ambitious study from scientists in Pediatric Research at the College of Medicine at the University of Florida. Until now, research on FA has concentrated on drugs and antioxidants that could treat symptoms of the disease. The UF researchers think gene therapy may be able to cure it.

Josh is hoping that his gamble pays off—if not for him, then for future generations of people diagnosed with FA. But he prefers not to learn about what will happen to him if a cure doesn’t arrive in time. In this sense, although Josh’s situation is unique, it offers insights into a dilemma that most people encounter at some point in their lives. On one hand, there are real benefits that come with facing our own mortality. But we can also gain strength by keeping ourselves in the dark.

“A series of losses”

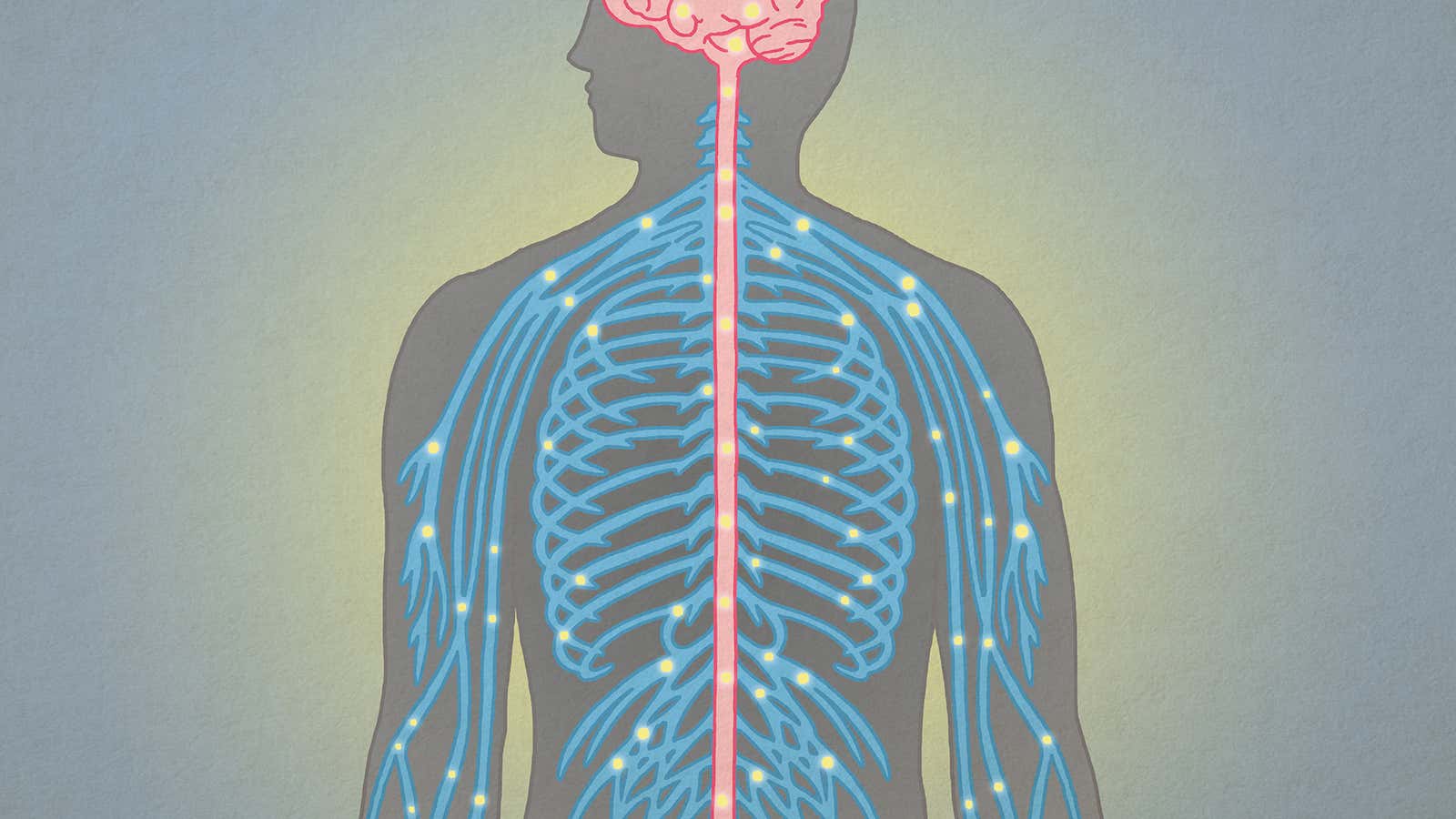

FA is a genetic condition in which the body fails to produce enough of a protein called frataxin. The lack of frataxin causes damage to the nervous system and weakens the heart. First the reflexes go; then the feet and legs slowly stop responding to messages from the brain. Kicking a ball, running down the street, or getting up from the couch become difficult, and eventually impossible. Finally, the heart gives out. Most patients with FA do not make it to their 40th birthday.

Josh began showing symptoms at around seven years old. His second-grade teacher noticed he was having trouble drawing a straight line—a task he’d been able to perform easily earlier in the year. His mother, Karla, brushed it off at first as a normal regression. But as he experienced more tremors and slower reflexes, she started taking him from doctor to doctor trying to find an answer. None were forthcoming.

“Right before his tenth birthday, he went to light a candle and his hands were shaking so much he couldn’t strike a match,” Karla says. “And at that year’s physical, he had no reflexes in his knee. I kept thinking, ‘Why isn’t the hammer moving?’ Your mind doesn’t go to anything really bad at first, you know? You want to write it off because this is your child.”

The Wootens were sent to a neurologist, but Josh’s brain and spine MRIs came back clear. The nerve conduction tests were normal. The final step was a DNA test, but doctors were confident that it would come back negative for FA. They were wrong.

“You’re standing in a room full of noise and all of a sudden the noise just stops,” Karla says. “Everything stops. There is no treatment. There is no cure.”

That same year, Josh stopped being able to ride his bike. His feet refused to move fast enough to peddle. He had to quit the soccer team because he could no longer change direction quickly, or move his leg to strike the ball as it came to him. Then he could no longer run or tie his shoes. Now, he cannot walk unassisted.

“The hardest thing with FA is that it’s a very slow grieving process,” says Karla. “You lose an ability and you suffer with that, and you then you get used to it. And then something else goes, and you do it all again. It’s a series of losses that you must become accustomed to.”

An eye toward the future

Karla says she feels the gutting emptiness of the future sometimes. She is constantly searching Internet boards, support groups, and universities for news of the disease. It’s her way of fighting off the idea that Josh’s fate is inevitable.

“When you think about losing a child, you lose your own heart,” she says.

But while Karla has immersed herself in research on FA, she works hard to prevent her son from entertaining dark thoughts. She has shielded him from detailed knowledge of his condition since he was a young child, although he’s taken part in numerous antioxidant trials and other experimental treatments.

“We did not expose him a lot to people with FA when he was younger, because I was afraid that he would be afraid,” she says. “I’ve always told him, you don’t know what you might be like because everyone is different. And he puts a lot of hope in that.”

Josh has continued to avoid exposing himself to unnecessary information. He’s never looked up anything about FA. He hasn’t sought out support groups, and he’s not up on the latest studies, apart from what he must do to take part in them.

“I don’t want to focus on how short my life will be,” Josh says. “I’m not going to focus on the end because the end could be tomorrow, even for a normal person … Like you don’t think about how short your life is going to be. Why should I?”

The search for a cure

New research could transform the outlook for Josh and others with FA. Three years ago, Karla Wooten read an article in the Gainesville Sun about Dr. Barry Byrne, one of the lead researchers on the new UF study. Byrne was researching Pompe disease at the time—an inherited disease in which of the accumulation of glycogen causes muscle weakness, enlarged organs and heart defects.

Karla saw many parallels between Pompe and FA. She called Byrne to ask if he’d considered researching her son’s disease.

One year later, Byrne called her back with the groundwork for a study in hand. They needed someone suffering from the disease as a starting point, so Josh volunteered his plasma and stem cells for testing.

The researchers had come up with a vector—a virus-like vehicle that would carry a drug throughout the body. They thought it might be possible to inject the drug, which consists of a non-pathogenic virus containing a normal copy of the human frataxin gene, into the human body. The drug would then enter the patient’s cells and release a functional fraxatin gene to augment the patient’s deficit.

“The goal of our research is to develop a definitive treatment for Friedreich’s Ataxia,” says Dr. Manuela Corti, another lead researcher on the project. “We are developing a gene therapy strategy that corrects frataxin deficiency in the heart and central nervous system by replacing the incorrect gene that causes the disease with a correct copy of the gene.”

The initial phases of the study have been completed. Researchers have now tested the drug—which has yet to be officially named—to see if it is safe and effective on mice. So far the results look promising enough that they are screening primates for their next phase, in which they will test not only drug safety and effectiveness but also the best place to inject the drug.

“The drug can be delivered by different routes, and one of the most important aspects of our research is to identify the best route of delivery to safely treat the heart and nervous system,” Corti says. “We are studying the feasibility of the combination of intravenous injection (in the blood stream) and intrathecal injection (in the spinal fluid).”

Assuming funding, drug production and animal screening continue on track, Corti hopes to begin evaluating the drug in humans in 15 months’ time.

Josh is ready and waiting. But he says he’s not counting on a cure.

“I don’t want to put all my eggs in one basket,” he said. “I’m hoping, but I don’t want to depend on it and be devastated if it doesn’t work. I live my life as if it’s not there to stave off disappointment.”

An independent life

For Josh, living his life to the fullest means maintaining as much independence as possible.

The teenager lifts his arm up to show me a reddish-purple burn that went from his elbow to his wrist. He grins sheepishly.

“I was cooking,” he said with a shrug. “I was straining pasta in the sink, and I fell backward. I threw my arm back to steady myself, and it stuck to the burner on the stove where the water had just been. I don’t know what degree burn it is—I just know it’s bad.”

Josh rents an apartment in Gainesville with two friends. His family moved to Jacksonville, 100 miles away, last year to be closer to ailing older relatives.

“We left him, and I still have guilt over that, but he wanted to stay and be independent,” Karla said. “And honestly, that’s the best thing we’ve ever done for him. He’s managing. He’s the stubborn, ‘I can do it’ kid.”

Josh’s roommates are happy to give help when he needs it, offering rides or cooking a meal. Karla also has good friends in Gainesville who would drop everything to help Josh in case of emergency. It’s worth the risk, she said, because it allows him to live as a person, not as a patient.

Josh is currently enrolled at Santa Fe Community College, where he is trying to decide between majoring in engineering or accounting. He just got out of a serious year-long relationship. He still drives, though he’s waiting on approval for a hand-controlled van so that he can transport a motorized wheelchair around campus. He goes to the gym three times a week, consciously working his dwindling leg muscles.

“Everything, physically, has gotten worse,” he said. “If this study really does provide a cure, I can recover from the physical stuff as I am right now, but once I lose enough muscle, that won’t come back, cure or not, so I exercise every day trying to keep them intact.”

His mother, meanwhile, hopes that Josh will wait to participate until after the first human phase of the study is complete. Given the dangers involved with undertaking any new therapy, most patients considering the testing phase in research studies like this are further along in their prognosis. In essence, they have nothing to lose. Karla doesn’t think that’s Josh.

“As much as I would love for him to be the first one to get the cure, I’m also nervous about it,” she says. “The purpose of a phase 1 study is to determine serious side effects and even death, because they don’t know what is going to happen in humans. Right now, Josh is functioning. He has challenges, but he’s living his life. And he’s got plans for the future. So, I’d be okay if they determine this is not going to kill people, and he takes part in phase 2.”

The stem cell technology that UF researchers are using could eventually help others, too, according to Corti. Stem cells are being studied and may be employed to fix other important chemicals and nerve structures—like dopamine in the case of Parkinson’s, joint structure in rheumatoid arthritis, and acid maltase in Pompe disease.

In the meantime, Josh is embracing the publicity that comes with his role in the study. “I can be the name in the article or the face in the magazine,” he says. “I feel like I can help a lot of people doing this, and being so open about it. It’s worth the pain and risk.”