The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the global body that keeps tabs on cancer risk, has studied nearly 1,000 “agents” to see whether they might be carcinogens. These agents run the gamut from very specific substances (e.g., plutonium) to broad categories of stuff (red meat) to broad classes of activities (working night shifts). And of all the things the IARC has looked at, there is just one it is pretty sure doesn’t cause cancer.

Now, there are two ways you might interpret this. One, which is how you might be leaning if you saw the recent reports that overly hot drinks might cause cancer, is that the IARC is a worrywart that sees cancer everywhere it looks. The other, kinder view is that the IARC is in fact fantastically good at choosing to study only those things that really do have a chance of causing cancer, so it almost never identifies something that doesn’t, and thus makes good and sparing use of valuable government money (it’s a branch of the World Health Organization).

In fact, the truth is somewhere between the two. And if it sometimes seems as if everything around you is suspected of causing cancer, that’s partly because of how the IARC classification works.

First, let’s look at the classification again, in simpler language:

Notice that fully half of the agents on the IARC’s list are in group 3—that is to say, it has studied them, but has no idea whether they cause cancer or not.

The IARC prioritizes studying substances that it thinks are likely to cause cancer. However, unlike humans in a court of law, chemicals are considered guilty of causing harm unless proven innocent. Once a chemical is suspect, it takes an extraordinary amount of evidence to acquit it.

As an example, take the recent re-classification of coffee. Along with its finding that drinks hotter than 65°C (149°F) may cause cancer, and should therefore be in group 2A, the IARC moved coffee—as long as it’s not too hot, of course—from group 2B (possibly causes cancer) to group 3 (lack of evidence). The working group reached that conclusion after analyzing more than 1,000 studies.

This means there are 500 agents on the IARC’s list that may well not have any cancer risk, but the IARC can’t be sure—and if it can’t be sure after 1,000 studies, who knows what it will take? Yet there they remain on the list, leaving everyone in doubt.

It also doesn’t help that even for agents in Groups 1 and 2, the IARC gives no information about how risky they are—only that there is some risk. Radioactive isotopes that would almost certainly give you cancer if the radiation poisoning didn’t kill you first are listed side by side in Group 1 with betel quid, which an estimated 600 million people around the world chew as a mild stimulant.

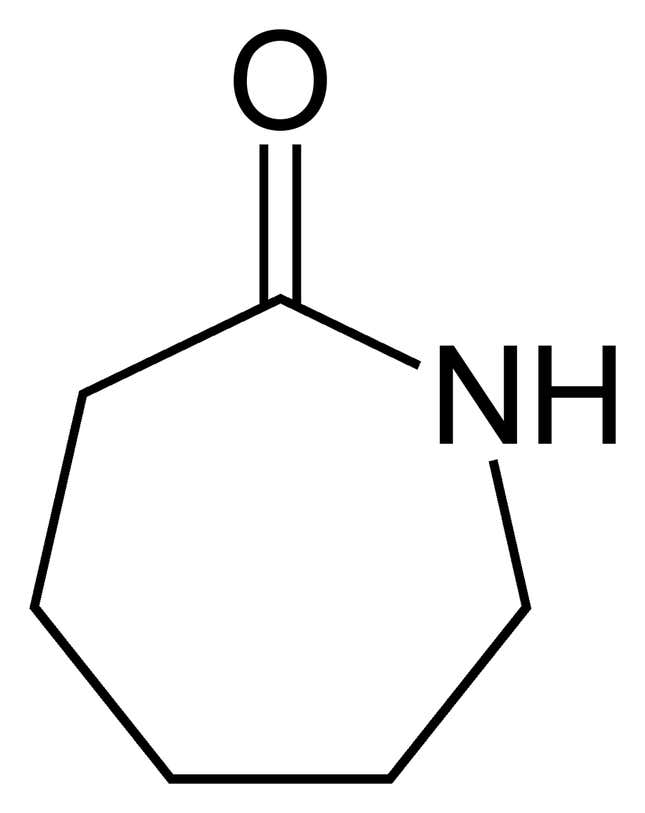

So what about that one substance on the list in Group 4, the probably-not-carcinogenic category? It’s a chemical called caprolactam, and we synthesize billions of kilograms of it every year to make nylon. Though caprolactam can be mildly toxic to humans, causing irritation and headaches, the IARC decided in 1999, after a re-evaluation, that it probably wasn’t a cancer risk.

You’d think the IARC must have looked at an extraordinary amount of evidence to reach that decision. In fact, its monograph cited only about 100 studies, and even noted that there had been no studies in humans to test caprolactam’s cancer risk. So how did it get the all-clear?

A historical quirk, seems to be the answer. Dana Loomis, deputy head of monographs at IARC, says the IARC working group at the time was convinced by the evidence to put it in Group 4. Today, the quantity and quality of studies evaluating a substance’s cancer risk has improved dramatically. This, Loomis thinks, means future classifications will require more evidence for a working group to change its mind—as shown in the case of coffee.

The short reason why more things don’t end up in Group 4, then, says Loomis, is the lack of resources. “If we were able to study everything, there would be more than one thing in that group,” he says.

So if it seems like everything causes cancer, it’s because there isn’t enough money to prove that it doesn’t.

In our Funny You Should Ask series, Quartz tackles your timeless questions about science and health. If you have a question you’d like us to answer, submit it here.