Images of people living in make-shift shelters, mud and squalor, have exposed the world to the living conditions in Calais’s refugee camp, known as “the Jungle”. But despite intense media coverage over the past year, it can be hard for outsiders to gain a true perspective on life in the camp, which has become a town in its own right.

For this reason, architect Shahed Saleem embarked on a project to map the Jungle. “This is a place of human endeavour and great human efforts. And it’s a place where lives are being lived,” he tells Quartz. “It’s much more complex than simply a place where people are trying to get across the channel,” he says.

The Jungle was partly demolished by the French government in March, and trouble and fires have broken out since, damaging more shelters. There are no formal maps of the camp, but it is still standing and its population continues to grow.

According to a volunteer-led census, over 5,000 people of 20 different nationalities, including Afghan, Pakistani, Sudanese, Ethiopian and Kurd, live in the camp, which is a former landfill site on the north coast of France. There are places of worship, a school, a women and children’s centre and, until recently, a theatre. There are also several shops selling necessities from toiletries to phone cards and restaurants, where fresh bread is baked every day.

A reluctant micro-society with its own economy has emerged, comprised of various communities, on the border of two developed nations. The Jungle is a transient, amorphous place, where the evolving geopolitical situation moulds the shape of its population. Saleem wants to convey these characteristics with the map.

“I was interested in the process that’s been happening there and the way in which that starts to have its own permanence, counter to any kind of political plan,” says Saleem. “It’s where other parts of the world congregate and you get clusters of cultural groups. I think that says a lot about human beings and the way they are—that they find a way of organizing themselves,” he adds.

Maps have the ability to shape our view of the world and our place in it. But historically cartography was used a means for political control: seemingly scientific maps are rarely totally objective.

Mapping a place that is as politically charged as the Jungle—where refugees are at risk of being targeted by both the French authorities and other groups who do not want them there—brings the problematic nature of mapmaking into sharp focus.

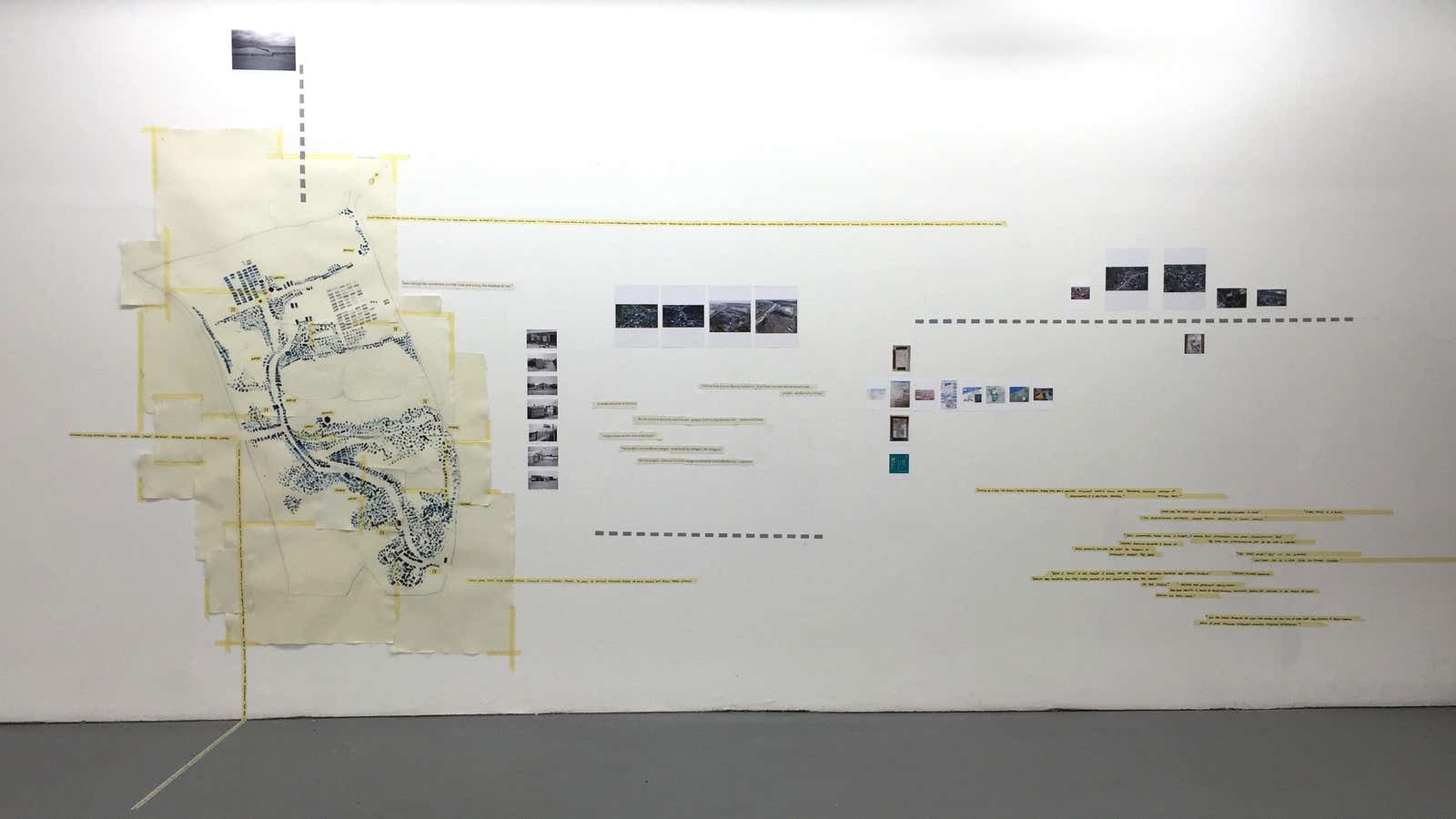

Saleem originally wanted his map to be an accurate record of the camp, but felt discomfort in mapping territory under these circumstances, especially since cartography has origins in colonial expansion. He decided a subjective map, based on his perceptions, and those of the students he teaches at Westminster University, would be more appropriate.

“So the map turns from pretending to be something that’s accurate and empirical to something that’s actually inflected with the subject. It kind of disrupts the point of it being an empirical accurate thing,” he says.

The finished work is being shown in London, as part of a wider exhibition by the Migration Museum Project on the refugee crisis in Europe running through June 22.

Saleem’s aim, to shed light on the complexity of the refugee crisis, is shared by another mapping project. The Refugee Project is an interactive visualisation that uses data from the United Nations Refugee Agency to show how various conflicts around the world have forced people to leave their homes over the past 40 years. “We wanted to understand the scope and reach of refugee migrations over space and time,” says Deroy Peraza, a Cuban refugee himself, whose agency Hyperakt created the map in collaboration with designer Ekene Ijeoma. “A map provides a familiar context that allows readers to see the ebbs and flows of migrations in geographic perspective” Peraza tells Quartz via email.

“Refugee population numbers are so massive that they’re difficult to wrap your head around,” he says. “Understanding how these numbers play out over space and time really helps to understand the gravity of a situation when you hear population numbers kicked around in the news,” he says.

Mapping projects like Peraza and Saleem’s aim to contextualise and inform outsiders about the global refugee crisis. But other than getting people to think about the plight of others, can maps directly help refugees living in camps?

The growing movement behind humanitarian open-source mapping would suggest so. Open-source mapping involves using free software like OpenStreetMap or MapBox to create online collaborative maps that anyone can contribute to. Increasingly, NGOs and aid organisations use these live maps in humanitarian crises, to get people the supplies and services they need. Getting people who are actually living in camps or temporary settlements involved in the mapping process makes this even more efficient, advocates argue.

“Traditionally it was always the government making the maps, but these days people can make their own maps, and the map is used as a political instrument also by community groups, with the help of NGOs,” Richard Sliuzas, associate professor at University of Twente, Netherlands, and expert in mapping slums and informal settlements, tells Quartz. “They can use that information to lobby and bargain with city or national authorities for attention for services,” he says.

In Dunkirk, about 25 miles north of Calais, a group of volunteers have been using OpenStreetMap to map the Linere camp there, with the help of refugees living in it. The open-sourced map includes water points, first aid points, places to worship and electrical outlets. The idea is to turn the live map into a paper one. The group says this project, called Mapfuges, is vital for getting aid to the residents, especially new arrivals.

Mapping temporary communities has its challenges. Not only do places change quickly but there are important questions about power and control to be pondered. With the enhancements to satellite technology and the prevalence of Google Earth, there isn’t much of the world that’s not visible. For people on the move and living in temporary settlements, mapping becomes a way of ensuring they don’t fall through the data gaps.

“It used to be that if you weren’t on a map, you didn’t exist,” says Siluzas. “Mapping is an important part of the process of being recognized.”