“Where did you get this painting?” I asked my friend with wide eyes and gaping mouth. It was our junior year of high school and somehow I’d never seen this print of my father’s painting in his living room.

“My mom bought it from somewhere,” he beamed. “Isn’t it amazing?”

“Yeah,” I nodded, smiling a little. “I remember smelling the paint fumes while he was still working on it!” My friend laughed harder than was necessary, harder than you would if you believed someone. My father had, indeed, painted it.

Chances are you’ve seen my father’s work—but don’t know his name. His art has shaped my life and inspired many. 25 years ago, he almost made a name for himself.

Elliot Miller, my dad, was born on Sept. 29, 1948, in the segregated, Jim Crow South. A black man from St. Louis, my father was poor for most of his life. He was the son of an uneducated minister with a drinking problem and grandson of a prize-fighting sharecropper.

He’d often tell stories about growing up, about the first time he picked up a pencil at age five and drew exactly what he had envisioned, as if it were already there and he’d merely traced the image from the page beneath. He also frequently discussed his complicated relationship with whites.

“Never trust a white person, Son,” he once told me while eating dinner.

“Why not, Dad?” I asked this question, already knowing it would lead to a story.

“Lemme tell you the white man’s plan for us…” His eyes rolled back while he went into a rant. Even his speech had color to it.

Thanks to him, I grew up around art during the 1990s in Chicago. We frequently discussed Picasso, Degas, and Chuck Close–they were some of the best distractions to the ailments of the city. In Chicago, fear, violence, and drugs were a stark reality of life. There was never a time when I’d pass up a museum trip. Even then, I was my father’s greatest fan.

I remember Dad made an uncanny 4 foot by 2 foot oil painting of Marilyn Monroe and leaned it against a wall. Marilyn wore that shimmering, curve-boasting dress that showcased the majesty of the female form; it was the dress that made a president blush on his birthday, the one that came with a flirty, overtly-sexual, almost whispered song. I used to sleep on the floor, close enough to touch Marilyn each night. I didn’t know who she was, but I knew I was in love with her. I’d reach my little hand up to make sure she hadn’t left during the night. She hadn’t. Then one day she was sold. I can’t remember the last time I cried so hard.

In the 1970s, my father made a painting for Muhammed Ali, presented it, and had his offer rebuffed by Ali’s then-manager, Bundini Brown.

Ali had been painted against a black backdrop. He looked like a king among men, his jaw slightly clenched, and his chin tough, bold, and seasoned. One could see the aquiline nose of his European side, his eyes sharp enough to sting like a bee. Sweat clung on his face like mist, and Ali appeared ready to jump out of the painting, like a tornado. However, Brown didn’t figure the rendition warranted a $20,000 price tag.

In those early days, my father wanted to generate interest in his work, giving it away on certain occasions. Few purchased from him. His love for community was rarely returned. He claims this is why he lost his hair early. I’m not so sure.

So, Dad took on several jobs—dish washer, a chef, and more. As a cabbie, a passenger once attempted to rob him at gunpoint. Luckily, his Army training kicked in and he was able to disarm the would-be-shooter. That turned out to be one of his last days as a cab driver. Despite not always being around, no one could accuse him of being absentee. My brother, sister, and I always felt his love and presence. We understood what he’d sacrificed for the family. And soon, many more would know.

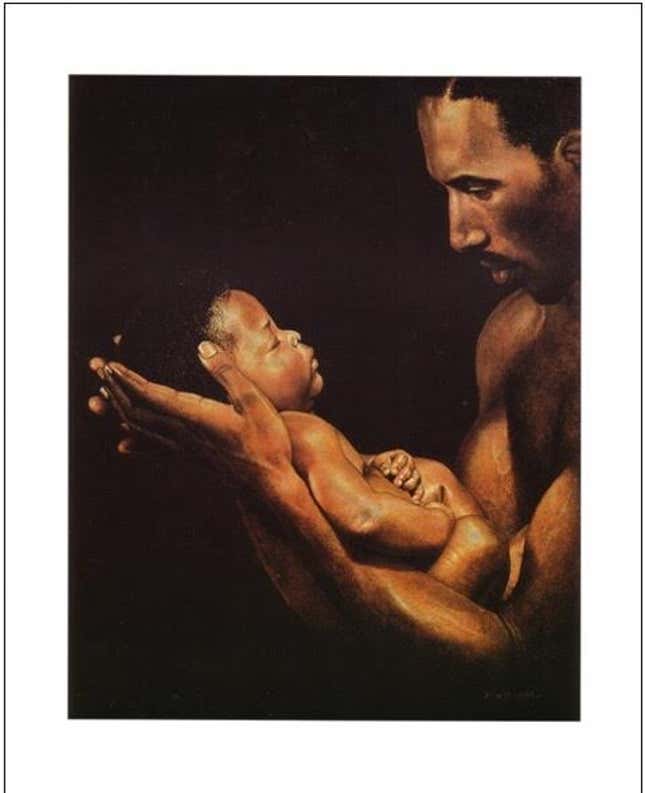

When my father created Father’s Love in 1991, it was a huge time for black-themed art. Guys like Charles Bibbs and Wak had revolutionized and revitalized interests in African American culture through inventive interpretations of the Diaspora. Father’s Love seemed to burst forth at just the right time.

The painting is simple enough: Black man, holding his child, amidst an onyx background. The power comes from the way he holds that baby, the juxtaposition of the strong, elegant Adonis, with the soft, chubby, Nubian prince. The detail of the tough, weather-beaten skin on the man is painted in many shades of chocolate and caramel and shows like glowing brown embers. The baby—neatly perched in a firm but gentle cradle inside the man’s hands—is dimpled, blemish-free, and velvety smooth. A bramble of curls decorates his head.

Through a painstaking process, my father created his magnum opus. He put layer upon layer of paint on the canvas, pausing in between to slowly bake the painting in the oven, an interesting technique employed by Renaissance artists. My father wouldn’t finish for a year.

Once he presented it, buzz for his painting spread. Major companies trying to capitalize on his talent swarmed. Eager to provide for his family, and still a naive young man, he sold his masterpiece for 10 grand, copy and print rights, re-distribution. Everything.

The company my father sold the painting to printed millions of them. Key chains, posters, coffee mugs and more followed. I’ve even seen the image printed inside Bibles.

There is a silver lining, though. Because of that piece, others have sought out my father. Famous football players, singers, and even Jimmy Carter have commissioned paintings from him. And he has no regrets.

I’ve always thought that this painting is a depiction of us. I often ask him about it. He’ll laugh and sigh, roll his eyes back and say, “Lemme tell you about business…” I never stop him when he begins to reminisce, even when I know the ending.