The fog still chills the morning air and the cable cars still climb halfway to the stars, yet on the ground, the city by the bay has changed immeasurably since Tony Bennett left his heart here. Silicon Valley and the tech industry has led the region into a period of unprecedented wealth and innovation. But existing political and geographical bottlenecks have caused an alarming housing crisis and astronomical rise in socio-economic inequality.

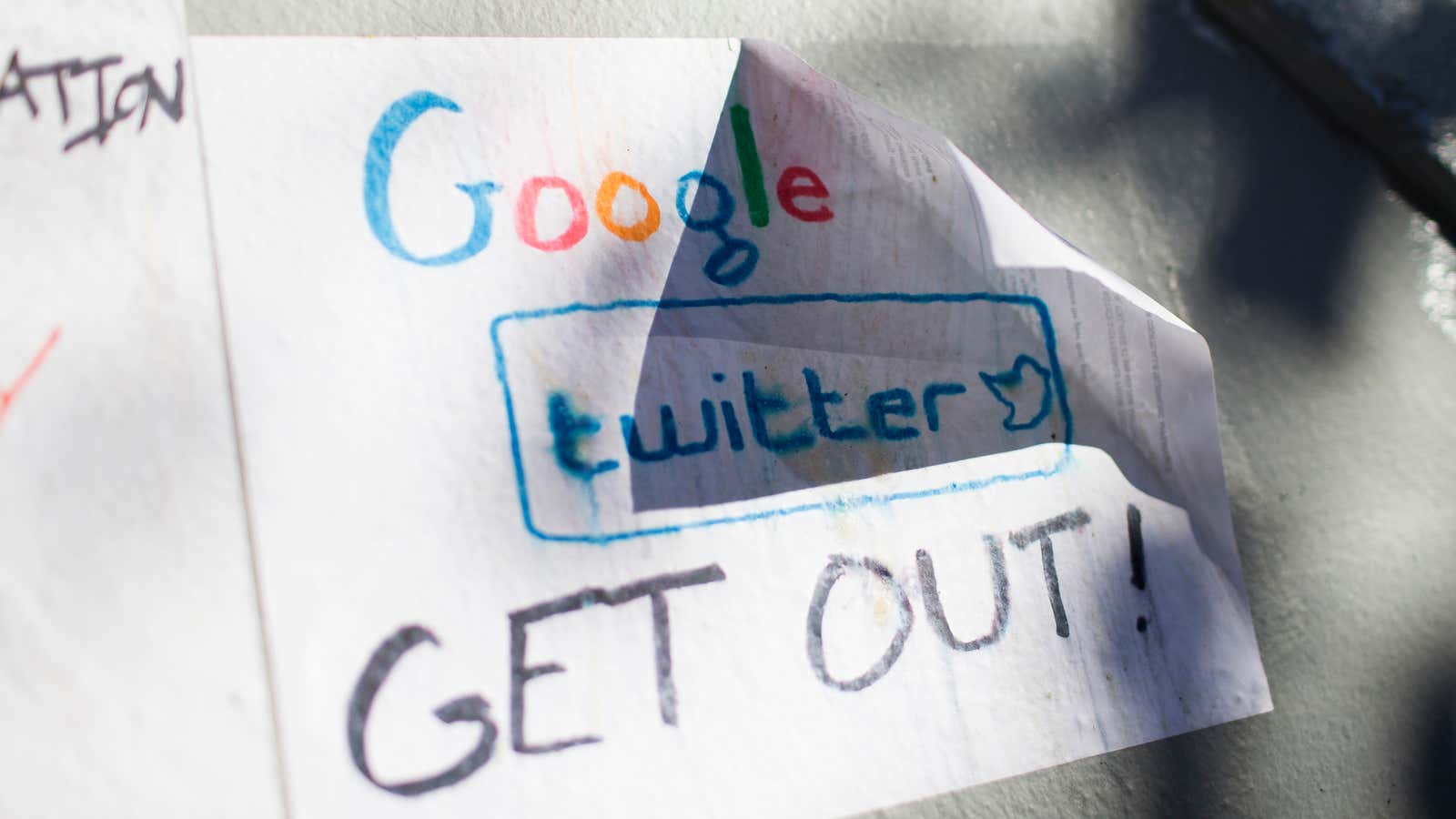

Whereas the citizens of most cities display pride and support for their home industries, drastic market distortions in the Bay Area have created a simmering underbelly of resentment in the region towards the tech industry. A vocal minority is even calling on officials to punish those who are benefitting from the economic and housing boom.

Undoubtedly, the prosperity and innovation that Silicon Valley brings are highly coveted net positives. However, if the spillover of this growth and its consequences are not resolved, a drastic increase in socio-economic inequality may have a profound impact on the region for generations. A history and analysis of this transformation may hold invaluable insights about the opportunities and perils of tech cities currently being cultivated across the US, and indeed around the world.

According to a recent study by the California Budget Center, San Francisco ranks first in California for economic inequality. The average income of the top 1% of households in the city averages $3.6 million, 44 times the average income of the bottom 99%, which stands at $81,094. The top 1% of the San Francisco peninsula’s share of total income now extends to 30.8% of the region’s income, a dramatic jump from 1989, where it stood at 15.8%.

The region’s economy has been fundamentally transformed by the technology industry springing from Silicon Valley. But due in part to policies pushed by mayor Ed Lee, which provided tax breaks for tech companies to set up shop along the city’s long neglected mid-Market area, the city is now home to Twitter, Uber, Airbnb, Pinterest, Dropbox and others. In short, the Bay Area has become a global magnet for those with specialized skills, which has in turn helped fueled economic vibrancy .

The economic growth has reduced unemployment to 3.4%, a commendable feat. But the strength of recent job growth combined with policies that have traditionally limited housing development in the city and throughout the peninsula has proven to be a perfect recipe for an affordability crisis. In 2015 alone, the Bay Area added 64,000 in jobs; in the same year, only 5,000 new homes were built.

With the average house in San Francisco costing over $1.25 million and median condo prices over $1.11 million, the minimum qualifying income to purchase a house has increased to $254,000, as estimated by the the California Association of Realtors. Considering that the median household income in the city currently stands around $80,000, it is not an exaggeration to say that the dream of home ownership is now beyond the grasp of the vast majority of today’s renters.

For generations, the stability and prosperity of the American middle class has been anchored by home ownership. Studies have consistently shown that the value of land has outpaced overall income growth, thus providing a huge advantage to property owners as a vehicle of wealth building. When home prices soar above the reach of most households, the gap between the haves and the have nots dramatically increases.

If causal factors leading to housing unaffordability are not resolved over multiple generations, the social stratification will start to resemble countries like Russia, where a small elite control a vast share of the country’s total wealth.

The result? A society where the threat of class warfare would loom large. According to a 2010 study conducted by the University of Warwick, a society’s level of happiness is tied less to measures of quantitative wealth and more to ties of qualitative wealth. This means that how a person judges their wellbeing in comparison to their neighbors has more of an impact on their happiness than their objective standard of living. At the same time, when a system no longer provides opportunities for the majority to partake in wealth building, it not only robs those who are excluded of opportunities, but also of their dignity.

San Francisco and the Bay Area have long been committed to values which embrace inclusivity and counterculture. To see these values fraying so publicly adds insult to injury for a region once defined by its progressive social fabric. In the face of resentment it is human to want revenge. But regressive policies such as heavily taxing technology companies or real estate developers are unlikely to shift the balance.

The housing crisis is caused by two primary factors: the growing desirability of the Bay Area as a place to live due to its vibrant economy, and our limited housing stock.

Although the city is experiencing an unprecedented boom in new housing, more units are sorely needed. Due to protectionist policies originally designed to quell bad development and boost historic preservation in our urban areas, too many developers are experiencing excessive delays. Meanwhile, there are the geographical limitations of the Bay Area to consider—the region is hemmed in by water and mountains.

It is clear that we live in a complex political and social environment. It is crucial that developers work with local housing groups to determine an acceptable standard of BMRs, or Below Market Rate units. Currently, the San Francisco planning commission, whose role is to advise the mayor and city departments on housing policy, is reviewing legislation that would increase the required amount of BMR’s for specified locations to 30% from the current 12%. In exchange, height and density limits for the project would be increased. This will help make sure that any new housing coming into the city won’t all be reserved for luxury units.

Local governments need to aid development as well. This means increasing zoning density throughout the region and building upwards while streamlining the approval process.

Real estate alone will not solve the problem, of course. Transportation, too, needs to be updated and infrastructure extended to link far flung regions to Silicon Valley and the city. We need to build an effective high speed commuting system linking the high priced and congested Bay Area with the low priced and low density Central Valley, dramatically shortening travel times. This system would constitute the “democratization of geography” by bringing once far flung regions within reasonable commute to heavy job centers.

Based on the operating speeds hovering of trains used in countries such as Japan or Spain, high-speed rail could shorten the time to travel between San Francisco and California’s capitol of Sacramento, or from Stockton to San Jose, to under 30 minutes.

By updating existing transportation routes combined with smart zoning policies that dramatically increase housing density in areas surrounding high speed rail stations, we will be able to build affordable housing within tenable commuting distances for a significant bulk of the workforce.

Our impending housing crisis forces the uncomfortable question of what type of society we would like to be. Will it be one where elites command the vast bulk of wealth and regional culture is defined by a cutthroat business world? We were recently treated to a taste of the latter, when local tech employee Justin Keller wrote an open letter to the city complaining about having to see homeless people on his way to work.

It doesn’t have to be this way. But solutions need to be implemented now, before angry mobs grow from nuisance to serious concern. It may take less than you might think. There are only so many housing reform community meetings one can sit through.

Ultimately, the solutions to our housing crisis are fairly clear. We need to increase the density of housing units. We need to use existing technology to shorten travel times and break the geographical bottleneck.

There is a way to solve complex social and economic problems without abandoning social responsibility. This is the Bay Area’s opportunity to prove that it can innovate more than just technology.