Child care in the US is so expensive that it’s making American parents unhappy. In some states, the average cost of having an infant under four in full-time childcare can be more than half a single parent’s income (pdf, p.27). In Massachusetts, for instance, where the median annual income for a single parent is under $26,000, the average cost of sending an infant to a child care facility is over $17,000.

For some families with two children in the Northeast and Midwest, the cost of child care represents the biggest household expense—bigger than housing (pdf, p. 32). For low income families with more than one child, the only option left is for one parent to temporarily leave the workforce, until the children are old enough to attend public school.

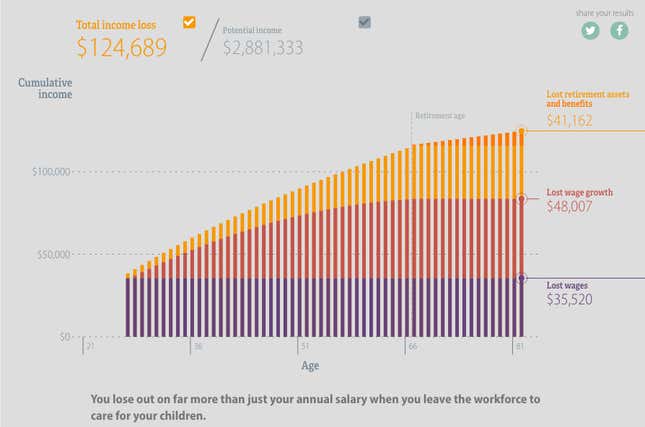

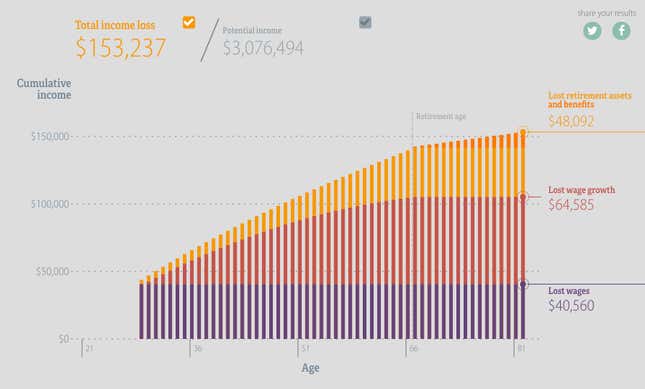

The Center for American Progress looked into the numbers (which can be consulted through an interactive infographic), and the findings help explain the career earnings gap for people who leave work and have children. For a 26-year-old woman (average age of first child) who earns $35,520 a year (average salary for women 25 to 35) and leaves the work force for one year to take care of a child, the combination of lost wages, lost wage growth and retirement benefit amounts to $124,689 loss of lifetime earnings, calculated over a work life of 42 years. For a man of 28 years (average age of the first child), the same scenario leads to a $153,237 loss, because men’s average salaries are over $5,000 higher than women’s at that age, and their wage growth tends to be faster.

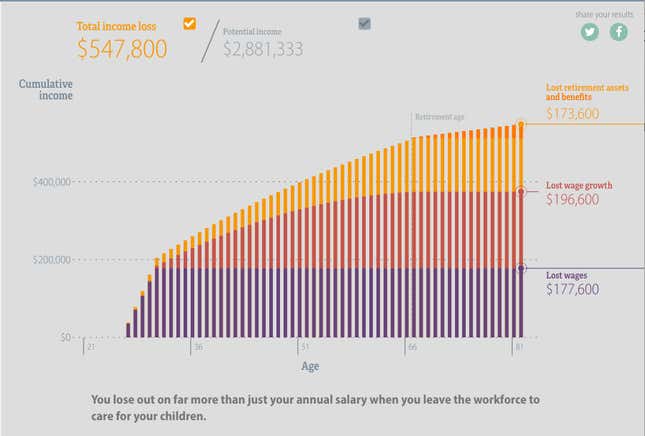

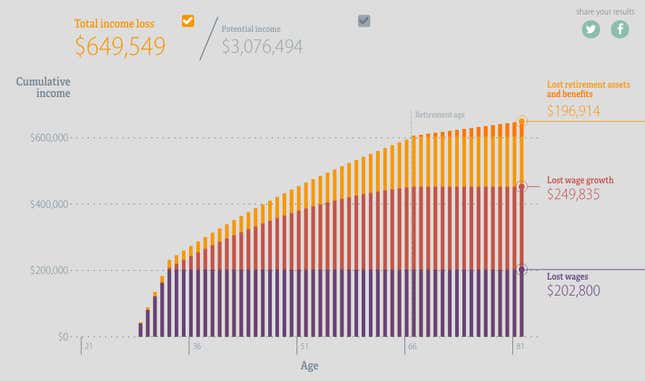

This gap could be partially addressed with parental leave policies that don’t require parents to take unpaid leave for a year after their children are born. But should parents stop working for five years, until their kids are old enough to enroll in a public school, a mother would give up on average nearly $550,000, and a father would lose nearly $650,000 in lifetime earnings.

Michael Madowitz, an economist at the Center for American Progress and one of the authors of the study, said that the ideal time off for new parents is six months to a year. After that, the burden on future income is truly sizable. “The nature of child care [in the US] is such that you have to take a hit for a few years before your kids can go to free school,” Madowitz said, explaining that many families resort to credit to cover the child care bills.

Lower income families pay the steepest price. They may have a harder time accessing credit, hence are more likely to choose to stay home. Given the progressive structure of Social Security, every year lost for low income earners has a higher impact in terms of lost benefits after retirement at age 66.

Women suffer the most. Since they earn less, and their projected losses are lower, it’s likely that a mother will take time off work to care for the children, therefore being even more penalized compared to her male counterparts once she gets back to work.

Madowitz says that the general policy conversation ignores the real costs of lost earnings due to child care duties and instead is focused on parental leave, with “the assumption that nobody loses when parents go home.” In reality, the loss is great and extended for years, but “we tend to shy away [from discussing it] because the solutions tend to be expensive.”

While the short-term cost of providing child care may be high for the government, it may not seem as steep when considering the long-term losses in wage and income growth for the economy as a whole.