Brexit could spell the end of the United Kingdom as we know it. After the majority of Scots voted “remain,” but the rest of the country opted for “leave,” Scotland’s leaders suggested the divergence justified another referendum on independence from the UK.

The Scottish National Party (SNP), which is the dominant political player in the north, explicitly states in its manifesto that grounds for another referendum include “Scotland being taken out of the EU against our will.” In 2014, 55% of voters in Scotland opted to stay in the UK. But in a post-Brexit poll, 60% of Scots said they’d choose independence if another vote was held.

They may want to reconsider. There is more to lose from leaving the UK than there is to gain from staying in the EU.

Granted, a major benefit of being part of the UK is membership in the EU. Indeed, retaining EU membership became a big part of the 2014 referendum campaign. Back then, it wasn’t clear whether the EU would let an independent Scotland into the EU without a lot of hassle, lest it encourage other separatist movements on the continent. Spurned by Brexit, the EU now may be more inclined to offer an expedient path membership to Scotland. But the economic case for Scottish independence is worse today than it was two years ago.

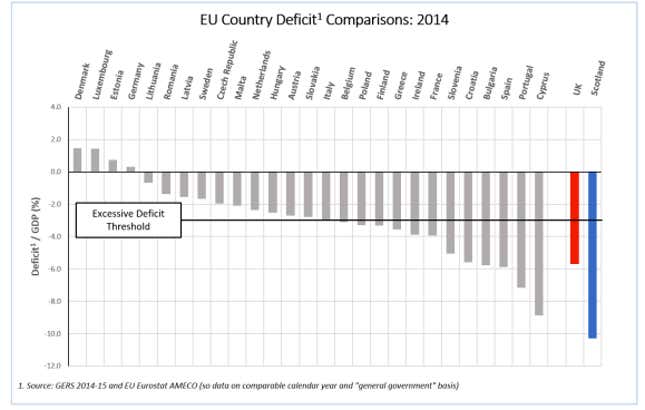

First off, an independent Scotland may not qualify for membership because its deficit-to-GDP ratio is nearly 10%. The EU demands 3% of its members, and even though it gives countries a fair amount of leeway, Scotland’s deficit is off the charts.

Scottish consultant Kevin Hague estimates that Scotland receives £9 billion ($12 billion) a year from the UK, or about £1,700 per capita. Scotland spends £1,500 more per capita on its residents than the rest of the UK, in part because of the age structure and rural make-up of the population. Over the past two years, dwindling North Sea oil reserves and falling energy prices have increased Scotland’s deficit, increasing its dependence on UK subsidies. Unless prices go back up or more oil is discovered, odds are that an independent Scotland would have to hike taxes or slash spending severely to qualify for EU membership.

That would imply Greek levels of austerity for Scotland, Hague says. It is possible, out of spite for the UK, that the EU would offer Scotland some concessions, but this is unlikely. Going easy on Scotland would be a bitter pill for the countries that have been through wrenching austerity and are already disenchanted with the EU.

The Scottish economy is also more integrated with the UK than the EU. In 2013, about 63% of Scottish exports (excluding oil and gas) went to the rest of the UK (pdf). Only about 17% went to the EU. The UK is arguably a healthier economy (although after Brexit it’s hard to predict the impact on growth for both the UK and the EU). Perhaps the UK will remain part of a free-trade zone with the EU and a newly independent Scotland that’s an EU member could continue to trade freely with UK, as it does now. But in that case there’s no real point, economically speaking, for Scotland to declare independence in the first place.

Money matters

There is also the question of the currency. During the 2014 referendum, the EU may have tolerated Scotland keeping the pound if it joined, even if the rest of the UK insisted that a formal currency union with Scotland was not an option. This time, neither the UK nor the EU would probably want Scotland to stay on sterling. Launching its own currency would be a huge gamble for such a small and vulnerable economy, and joining the euro wouldn’t be much better. Adopting the euro would mean losing control of monetary policy tailored to Scotland’s circumstances, which could worsen the likely austerity (just look at Greece). Hague says the prospect of adopting the euro “may be jumping from the frying pan and into the fire.”

The UK will surely pay a price for leaving the EU, but in relation to Scotland it is a larger economy that’s more resilient to negative shocks. Its economy is more diversified than Scotland’s and it can finance deficits by borrowing relatively cheaply in international capital markets. Scotland’s energy-dependent economy is shakier, the country has less clout on the world stage, and takes a bigger gamble by leaving the UK.

A passionate supporter of the UK staying in the EU, Hague says he is undecided about Scottish independence. His decision will depend on many things: the conditions of EU membership for Scotland; whether a post-Brexit Britain can still afford to subsidize Scotland; and the relationship between the UK and EU once divorce negotiations are over. In spite of the enthusiasm for independence today, Hague says, “it still far from clear that it will be a sensible in light of day when faced with stone hard facts.”