After months of waiting, Vietnam’s public finally has an explanation to the mysterious fish die-off that started in early April, lasted two to three weeks, and devastated the local fishing industry. As some suspected, the cause was pollution from a new Taiwanese steel factory, the government’s environment ministry said today (June 30) in much-anticipated press conference.

It isn’t often that a nation’s military is called upon to bury tons of dead fish, but that’s just what Vietnamese soldiers were doing a few months ago, after government researchers determined that “toxic elements” were responsible for the massive die-off of fish, clams, and other marine life.

The die-off occurred along 200 km of the nation’s north-central coast, as well as in nearby fish and shrimp farms. In late April the government banned the sale and distribution of non-living aquatic products in its region, for fear of contamination in the food supply.

Fishing and tourism in the area have been hit hard by the ecological disaster, which also contributed to slowing economic growth for Vietnam in the first half of this year. The fisheries sector accounts for 4% to 5% of Vietnam’s GDP and employs more than four million people. The nation’s seafood industry is worth $7 billion a year in exports.

As Vietnam increasingly attracts foreign investment in manufacturing, with firms like LG, Samsung, and Panasonic looking for cheaper labor than China using it as an assembly base, the risk of environmental pollution is rising.

An early suspect

Since early May the government has been conducting a probe with international experts into the exact source of the pollution that caused the die-off, promising an announcement of the results by the end of this month.

Soon after the fish deaths, the public’s attention turned to a new steel plant in the area owned by Formosa Ha Tinh Steel, a subsidiary of Taiwan-based Formosa Plastics Group, which has been linked to environmental problems in other countries (see below). The plant, in the Ha Tinh province, has wastewater pipes leading to the sea. Local fishermen reported seeing red water coming from the pipes before the die-off began.

State media initially blamed the company, but then backtracked. In late April government officials said there was “no proof yet“ that Formosa was responsible for the disaster.

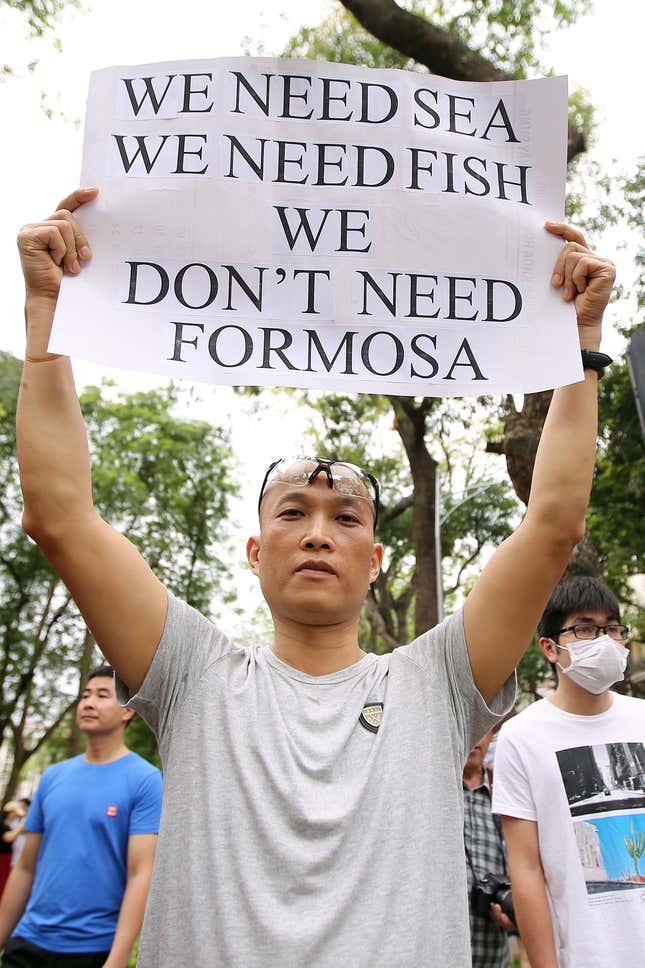

Public demonstrations soon erupted in cities throughout Vietnam, with protestors calling for environmental protection and action against Formosa. The government cracked down on the rallies by intimidating or arresting protestors, Amnesty International reported on May 20 (pdf).

A protest was also held in Taipei in mid-June, with demonstrators, environmentalists, and activist shareholders in Formosa calling on the company to investigate the fish deaths and share its findings.

Taiwanese lawmakers also urged a government investigation in mid-June, noting that the disaster could jeopardize president Tsai Ing-wen’s policy of promoting investment in Southeast Asia in order to reduce Taiwan’s economic reliance on China.

Vietnamese-Americans, meanwhile, urged the US Food and Drug Administration to thoroughly test and inspect all seafood and fish products imported from Vietnam following the deaths.

The company released a statement in late April saying it was “deeply surprised and sorry” about the fish deaths, adding it had spent $45 million upgrading the wastewater treatment system at the $10.6 billion steel plant project, one of the largest foreign direct investments in Vietnam.

But a company spokesman was less diplomatic in an April 25 VTC News interview (link in Vietnamese): “Before acquiring the land, we already advised local fishermen to change their jobs,” said spokesman Chu Xuan Pham. “Many times in life, people have to make a choice: either to catch and sell fish, or to develop the steel industry. We cannot have both.”

In a letter to employees today, the company wrote, “We respect the government’s investigation results and are cooperating with the authorities to handle and mitigate the consequences.”

At today’s press conference a government spokesperson said the company would provide $500 million in compensation for those affected, and played a video of its chairman apologizing and expressing regret over the disaster.

Formosa’s past troubles

Environmental problems have followed Formosa Plastics Group in the past. In 2009 it ”won” a Black Planet Award from Ethecon, a German environmental group, which is given to companies deemed to be destroying the environment. Among other incidences, Ethecon noted that in the 1998 the company dumped 3,000 metric tons of toxic waste into the Gulf of Thailand close to the Cambodian city of Sihanoukville, a popular destination for international tourists.

According to a BBC report in 1999, Formosa apologized to Cambodia but refused to accept responsibility or pay compensation. “Senior government officials have alleged that up to three million dollars in bribes may have been paid to corrupt officials to allow the waste into Cambodia,” the BBC reported.

In a May 1 report from Radio Free Asia, oceanographer Nguyen Tac An said the nation’s scientists were largely in agreement over the cause of this year’s die-off. “Scientists have found out how much waste there was, and how toxic it was,” he said. “They have satellite pictures from April 6 to April 20 to back up what they calculated.” But while the government had the information, he added, it had yet to release the information to the public: “This is the government’s decision, not the scientists’ decision.”

Rethinking Vietnam’s fast growth

The disaster has prompted scrutiny into how factories are approved in Vietnam.

Recently the Vietnam Association of Seafood Exporters and Producers expressed concerns about the potential impact of a $1.2 billion paper plant slated to start in August in the nation’s southern Hau Giang province. It worries the plant, backed by the Lee & Man Paper Group of Hong Kong, could cause environmental pollution and contaminate seafood.

The plant’s obsolete technology and use of various chemicals will spell disaster for the area, warned Le Huy Ba, an environmental management expert at the Industrial University of Ho Chi Minh City, in a Radio Free Asia interview. He noted that environmental impact assessments are usually commissioned by project investors who pay eager-to-please consultants to conduct them.

In light of the fish die-off earlier this year, both national and local environment ministries were recently asked to scrutinize the factory’s plans, facilities, and permits.