Dan Nakamura is the sonic sorcerer behind the techno-gothic sound of chart-toppers by artists such as Cornershop, INXS, Depeche Mode and Gorillaz. In the early and mid-Oughties, better known as by his nom de tune, “The Automator,” Nakamura was one of the music industry’s handful of superproducers. When I ran into him last year at South by Southwest (SXSW) in Austin, Texas, he was miffed to hear from me that a leading music blog had posted a lengthy where-are-they-now feature story titled “Whatever Happened To: Dan the Automator?”

“Listen—over the past five years, I’ve produced two No. 1 hits in France and three in the UK,” he said. “In England, over the past 10 years, I probably have more hits with more different people than any other American. The problem is, they’re all with artists no one in the States has ever heard of.”

He’s not kidding. The Love Album, which he produced for nouvelle chanson diva Anais Croze, was a top-five disc on the French charts, but a world-music obscurity in America. The two records he made for British swag-rockers Kasabian, West Ryder Pauper Asylum and Velociraptor!, both hit number one in the UK and have been certified gold in multiple countries around the world. In the US, they vanished without a trace.

This year, Americans will be getting an earful of Automator, with the release in January of Pillowfight, his addictively groovy lounge-hop collaboration with alt-violinist Emily Wells, and his long-awaited followup to the underground rap classic Deltron 3030 poised to drop this summer. But his situation nevertheless begs a very real question: Are sales in the US market still the go-to standard of global pop-music success?

After all, by some metrics, America’s music market isn’t even the biggest in the world anymore: In 2010, Japan surpassed America in sales of physical music (e.g., CD albums and singles, as well as music-video DVDs) — it’s the only major market in the world where nondigital music sales are actually still growing, year over year. And the vast bulk of those recorded-music revenues go into the pockets of locals. Only about 20% of music dollars in Japan are spent on foreign artists, with the biggest-selling performers being almost exclusively Japanese: Sixteen of the nation’s current top 20 songs are by domestic acts, with the sole US performers on Billboard’s Japan hit list being Justin Timberlake & Jay-Z (their “Suit and Tie” peaked at #4 and is now fading at #7) and Bon Jovi (who peaked at #5, and are sitting at #16 with “Because We Can”).

And as diverse as America is, its mainstream music market is even more insulated from outside musical invasion; the only non-domestic artist currently on the US Billboard charts is Scottish DJ Calvin Harris. And with the exception of performers from Anglophone markets like Canada, the UK, Ireland, Australia and parts of the Caribbean, it’s proven virtually impossible for foreign acts to achieve sustained Stateside success. In fact, there’s exactly one performer who’s charted more than three top 20 singles in the US despite beginning her career in a non-English-speaking country: Colombia’s Shakira. (Proving the assertion that hips, indeed, do not lie.)

The record of Asian pop and rock artists who’ve challenged the US has been an unmitigated disaster. PSY, take note: Asia’s list of transpacific crossover can’t—misses who’ve ended up capsizing include not only fellow Korean Rain, but Hong Kong’s CoCo Lee and Japan’s Seiko Matsuda, Puffy AmiYumi and, most recently, Hikaru Utada.

On paper, Utada is the ideal crossover candidate. For one, she launched her assault on US shores as Japan’s most popular singer ever. She’s made three of the top 10 best-selling albums in Japanese history, including the record that still sits at number one today, First Love. She’s sold more than 70 million records worldwide, half again as many as Shakira. And of course, there’s the fact that she’s actually American—born and raised in Manhattan, educated at Columbia University, and totally fluent in English.

Her first two English-language records, Precious in 1998 and Exodus in 2004, showed some promise. One single from the latter, “Devil Inside,” even briefly topped the Billboard dance charts. But 2009’s optimistically titled This Is the One was supposed to make her a household name in the country of her birth. As you know if you’re reading this, it didn’t. In the US, the album has sold fewer than 30,000 copies. By contrast, in Japan, where its lyrics were incomprehensible to most of its audience, it sold 78,000 in its very first week and went on to be certified platinum. After this final confirmation of the futility of making it big in America, Utada returned to her adopted country, released a double-platinum “Best Of” collection, and announced an indefinite hiatus from pop music.

Since Utada’s crash and burn, Asian acts still make occasional, desultory Stateside appearances, primarily in packaged concerts targeted at the fanboy and hipster crowds. SXSW Music regularly features artists from Southeast Asia, Taiwan and South Korea, and has sponsored a “Japan Nite” every year since 1997. But those performers come to the festival with few pretensions and no delusions.

“It’s not about being a big star in the US,” says Singaporean rocker Inch Chua, who played SXSW in 2011 and 2012. “It’s about learning things in America to bring back home.”

Chua, who fronts a band she’s dubbed The Metric System, believes that the music scene in Asia is poised to explode. “I think Asian artists have so much to offer the world, and I think we’ll eventually be able to export our music in a big way,” she says. “But not now, and maybe not soon. I think it’ll take a decade or so for work people are trying now to really show results.”

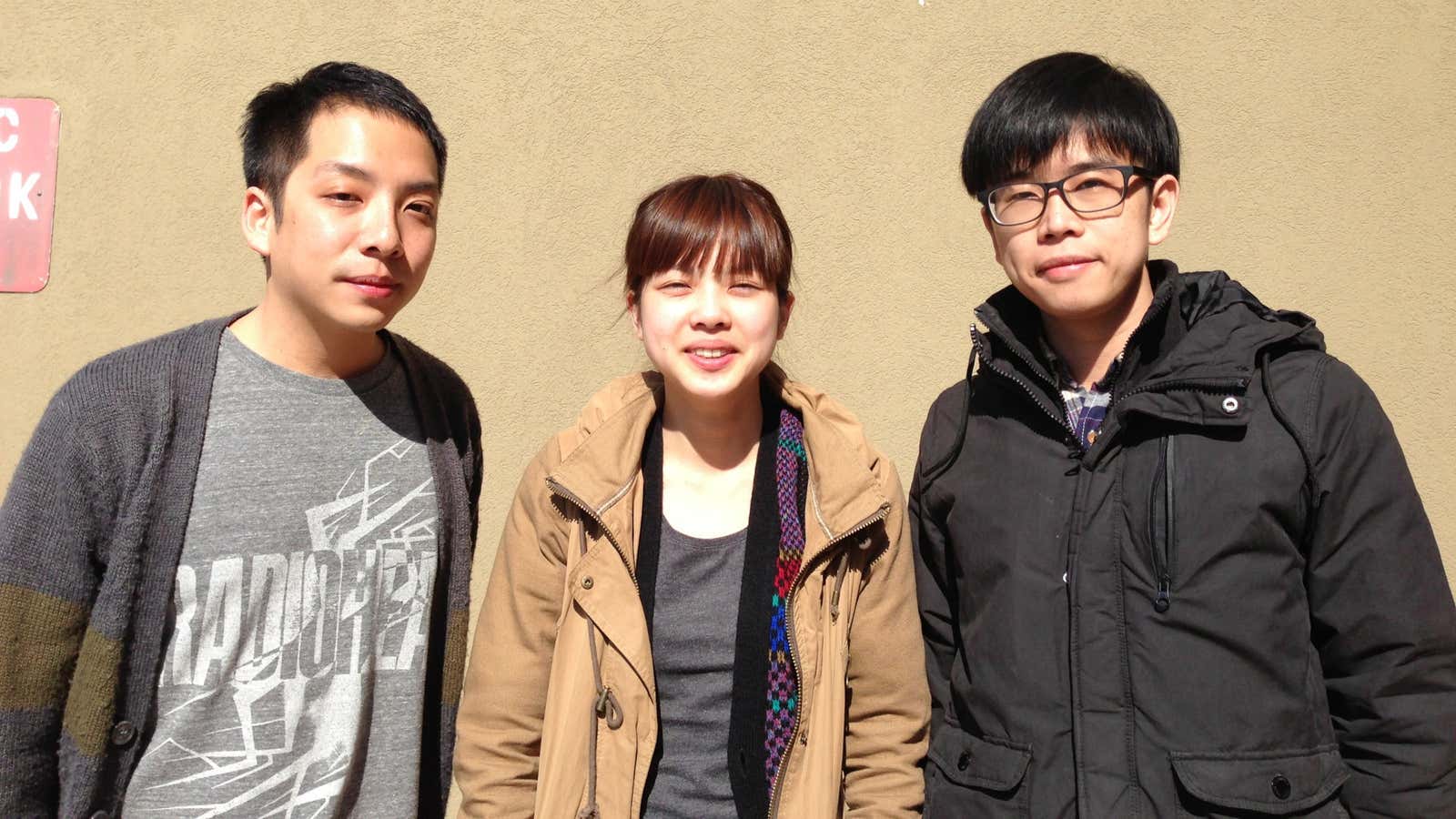

For now, America is being seen by most Asian artists as less of a market opportunity than a classroom, a laboratory and a proving ground. Taiwanese rockers Manic Sheep, a trio featuring bandleader Chris Lo on bass and vocals, guitarist Scott Hsieh and drummer Yi-Ta Tsai, made their US debut at SXSW this year, bringing their eclectic, dreamswept brand of alt-rock to Austin alongside three other groups from Taiwan, all selected via an online application process.

What distinguishes Manic Sheep is that the band performs almost exclusively in English. “We’ve been around for two years, and made one album, but that album caught the attention of Ling Ma Wang, probably the most famous rock critic in Taiwan,” says Lo. “He gave a really good review to one of our first performances, and a bunch of people became our fans really quickly,” despite the English-language lyrics.

For Lo, writing in English was a way of achieving security through obscurity: “My music is really personal, and I don’t want the people around me to know too much,” she laughs. “Our English actually isn’t so good, but I figured that if I used it, it would be safer, since people wouldn’t really know what I’m saying. It annoys our fans, though. I finally gave up and translated two of our songs into Mandarin.”

The unintended consequence of singing in English is that, given the boundary-free nature of digital promotion and distribution, the band’s fanbase has expanded overseas almost by accident.

“Half of our music sales are digital,” says Lo. “We’re on Bandcamp, and we got on iTunes a few months ago, and what we’ve found out is that most people purchasing our music are from outside Taiwan, mostly from Australia and New Zealand.”

In the US, however, Manic Sheep remains totally anonymous, and members are basically okay with that. “We came to SXSW to watch how other bands perform,” says Lo. “In Taiwan, music is all about live concerts. People don’t buy records so much anymore, so you can’t just have good music, you have to be good performers. So we came to Austin to check out bands we like, to see if they’re any good live too, and to learn how to improve our own performances.”

SXSW has cachet back in home as well. “Most Taiwanese who really know music have heard of SXSW, so it’s like a mark of approval to say we came here,” says Lo. “And it’s even bigger in other parts of Asia. Telling distributors we were performing at SXSW opened a lot of doors.”

From Austin, Manic Sheep traveled to Toronto for Canadian Music Week, and are now in New York, performing a handful of concert dates that they managed to secure via email. Next week, they return to Taiwan and reality. But they’re hoping that what they’ve learned on tour will help them break through in the markets that matter to them the most: “I really want to go to Japan,” says guitarist Hsieh. Lo agrees. “Japan understands rock and alternative bands, and we think we can find a lot of audience there, because rock fans there like to listen to songs in English. But eventually, we hope to go to Mainland China. Alternative music is growing very fast there. Within five years, their musical tastes will be even more sophisticated than Japan. So that’s what we hope to do: We’ll go home, finish our next album, go on tour in Japan, and then, somehow, we’ll find our way to China.”